How vividly did the Guadalcanal campaign impress itself on the American imagination? Well, this movie was released around nine months after the last Japanese soldiers were driven from the island.

But all the media were moving at fast pace in those days. In propaganda, as in so many other things — internment of undesirables, terror-bombing of civilians —, the Nazis established the standard that their enemies emulated. The Wehrmacht invaded Poland on 1 September 1939 and by November the official documentary film, Sieg in Polen, was being shown in New York City, where it was seen by, among many others, W. H. Auden and Thomas Merton. (This was the subject of one of my first scholarly articles.) Likewise, in June of 1942 John Ford carried a camera with him to record what would become known as the Battle of Midway, and the edited footage appeared as a short film in September, with a score by Alfred Newman and narration by Henry Fonda.

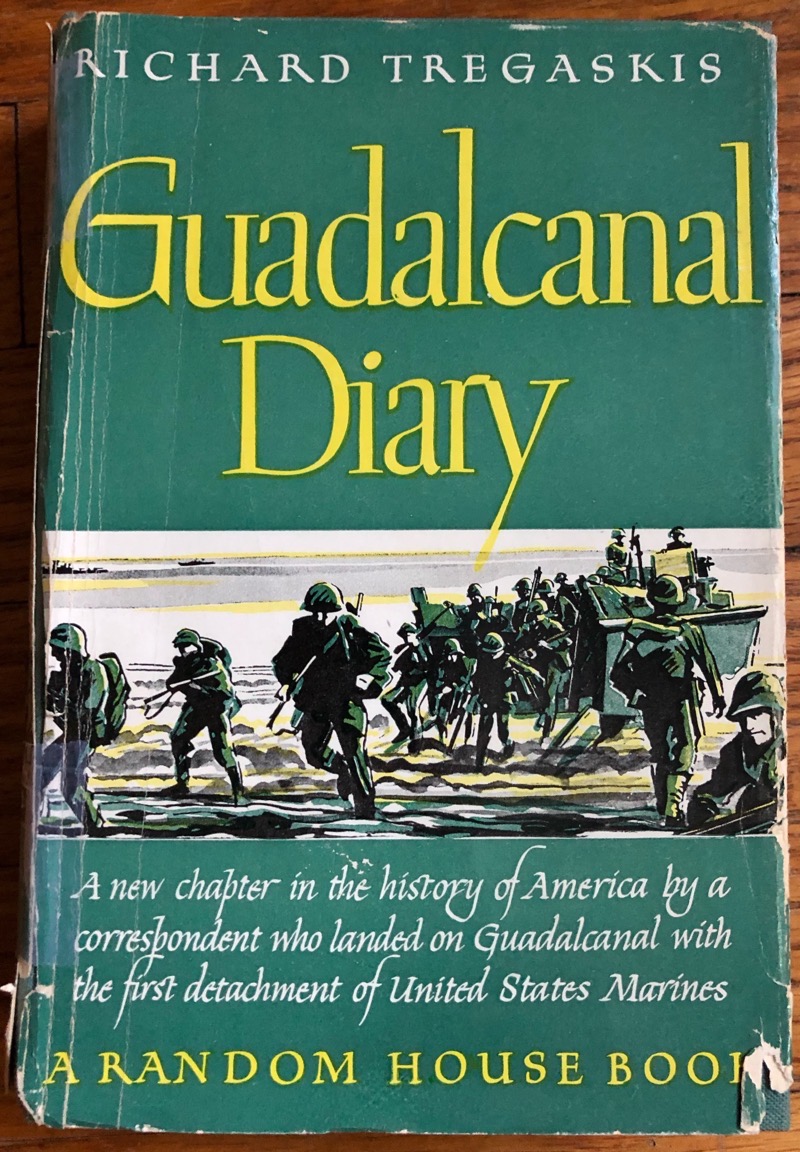

And when the Guadalcanal campaign began shortly afterward, a young journalist for Life magazine named John Hersey accompanied the American troops, as did Richard Tregaskis, a reporter for the International News Service. Both of them sent dispatches from the front which were published immediately, and then quickly turned them into books: Hersey’s Into the Valley and Tregaskis’s Guadalcanal Diary were both published on the first day of 1943. The latter was, in a vague sort of way, the basis for the movie.

Tregaskis’s book — and this is a point to which I will return in later installments of this series — is bookended, as any account of an island battle is likely to be, by sea journeys: an arrival and a departure. Landing craft deliver soldiers to the island; the soldiers enter the hell of battle; eventually those who survive, relieved by new soldiers, return to the landing craft and are conveyed to a place of rest. (The First Marine Division, who had begun the invasion in August, were relieved in early December and taken to Melbourne, where they were greeted, quite properly, as great heroes.) There’s something intrinsically ritualistic, almost mythic, about this pattern.

But there’s also, in the context, something consoling about it.

The movie of Guadalcanal Diary maintains this structure: the first twenty minutes show the Marines on ship headed towards battle, demonstrating camaraderie among regions and races: a very young black soldier has a speaking part! One of the chief characters is a Mexican-American! (One of the few times in his career that Anthony Quinn played his own ethnicity.) They grow slightly more anxious, though, before landing on … an undefended beach. (This is one of the better effects of the movie — the anticlimax of arriving for battle and finding no one to fight.)

Eventually they encounter the enemy first in small numbers — the initial battle set-piece enacts an event Tregaskis made famous, the Goettge patrol — and then in larger numbers, until we approach a final battle, preceded by prayers, confessions of dis-ease, and letters home to families. In that battle one of the leading characters — it had to be Alvarez, didn’t it? — is killed, and then the Marines are relieved. At the end they’re marching towards the ships that will take them away, and the narrator — a version of Tregaskis — is pleased to say that they’ll receive “a well-earned rest, the job superbly done. The Army is coming in to take over. Into their hands we commit the job, with full confidence in their ability to perform it.”

And that’s the consoling message, for soldiers but perhaps especially for the families of soldiers: the fighting will be tough, but it won’t last too long, and almost everyone will survive. No need to get too anxious.

When the movie came out, James Agee wrote that it “is unusually serious, simple, and honest, as far as it goes; but it would be a shame and worse if those who made or will see it got the idea that it is a remotely adequate image of the first months on that island.… I think it is to be rather respected, and recommended, but with very qualified enthusiasm.” In that note Agee said that he hoped to write at greater length about the move, but, alas, it appears that he did not. I would very much have enjoyed hearing what his reservations were. Mine, as the above summary suggests, are significant. I thought it clichéd and profoundly unrealistic in every respect; though perhaps in comparison to still-more-jingoistic endeavors it was not.

(Also: the movie has quite a number of Asian or Asian-American actors playing Japanese soldiers — not one of whom is named. I would give quite a lot to know who those men were, how they were cast, and what they thought about the whole business.)

Now, back to real life: one of those Army men who relieved the Marines on Guadalcanal was James Jones, and he wrote about his experience in the novel The Thin Red Line (1962). Soon after that book’s publication, Jones wrote an essay for the Saturday Evening Post called “Phony War Films.” He explains how, after his return from the war — he was discharged from the Army in 1944 because of a bad ankle, an experience that he gives to Corporal Fife in The Thin Red Line — he found himself laughing incredulously at war movies. Sometimes he even walked out on them. Then, almost two decades later and in preparation for writing his article, he watched a bunch of more recent films about the war he had fought in. His verdict:

When I finished, I was not only almost cross-eyed from watching film, near death from explosive sound effects, I was more depressed with the essential adolescence of America (maybe I should say of the race) then I have perhaps ever been. If our war films are indication of our social maturity in an age when we have the capacity of destroying ourselves, there is little hope for us….

Now, why is this? Why, after so much soul-searching by Americans, so many advances in so many other fields during the past twenty years, have war films remained at the same, essentially adolescent level as the war films of 1943?

Jones’s basic answer is that the film studios are giving people what they want.

By the way, that essay — which as far as I can discover is not available online — is reprinted in the booklet that accompanies the magnificent Criterion Collection edition of Terrence Malick’s film The Thin Red Line. And yes, that’s where this series is headed … but we still have business with James Jones and his novel.