Around the rim of the shield Hephaestus made for Achilles is the Ocean River, the great water that (Homer believed) rings our world — Middle-earth, it’s sometimes called: the place where we live and, often enough, fight and kill and die. And, as I have noted, Guadalcanal Island is ringed by that very ocean. Guadalcanal is thus a kind of microcosm, but one in which the agonistic character of life, the struggle that reveals who we are, is accelerated and intensified.

Hephaestus’s ocean is a kind of frame, and these stories of Guadalcanal I’ve been exploring are all necessarily framed by the passage across the waters to and from the place of struggle. But what Terrence Malick does in his film The Thin Red Line is add another layer of framing. His version of Guadalcanal does not begin with the crossing of the liminal sea, but rather with two additional contexts.

The first shot of the film shows a crocodile slipping into water; the last shot of the film shows a small young leafy palm standing, somewhat unexpectedly, in shallow water on a beach.

That first shot is followed by a scene in which we see Jim Caviezel’s Private Witt enjoying the company of a seaside Melanesian community. (We later learn that he’s not taking a vacation, he’s gone AWOL.) Then we shift to the transport ship taking the soldiers to Guadalcanal.

That last shot is accompanied by a sound: the sound of a Melanesian a cappella choir singing one of the songs we heard them singing in that early scene. This is immediately after we see a transport ship removing the soldiers from Guadalcanal.

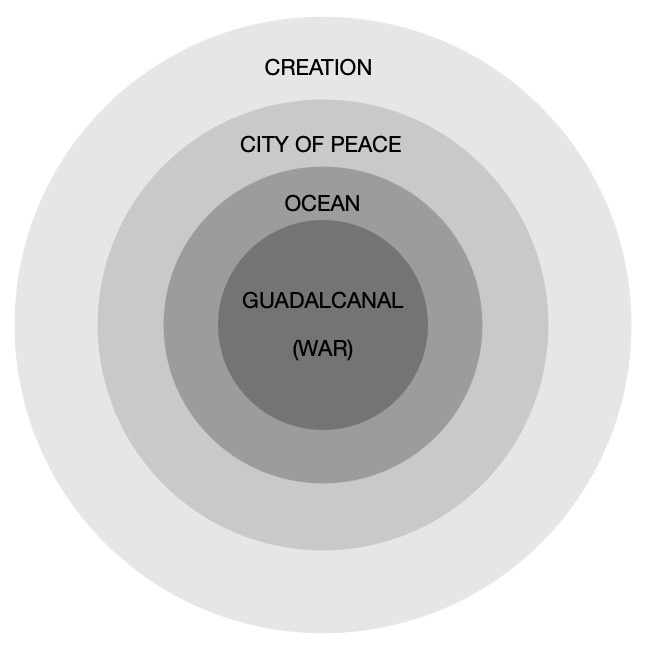

So The Thin Red Line gives us four … let’s call them existential layers.

A key question for any one soldier — well, actually, any one human being — is: How many of these layers do you perceive? How much of what is is perceptually and epistemologically available to you?

There’s something fundamentally disorienting about Malick’s movie. On the one hand, as I noted in an earlier post, the soldier who confronts another soldier in battle, in the agon, is confronting himself. And this is existentially harrowing.

But notice that Private Witt has no interest in the agon. After he goes AWOL among the Melanesian islanders and is forcibly returned to his unit, Sergeant Welsh removes him from battle duty and makes him a stretcher-bearer. Later, he pleads to be returned to battle, not because he wants to fight, but simply because C-for-Charlie Company is, he says, “my people.” We see him tending to the sick and then, at the end, drawing Japanese soldiers away from the other members of his company — and by so doing sacrificing his life. He lifts his weapon in that last moment, but not to fire — rather, to draw fire from the soldiers who surround him.

Private Witt undergoes his own agon, but it is not that of the warrior. Before that final confrontation, he has already faced himself — not as Hector faces Achilles but in a very different way. He had received a kind of revelation, and he is capable of receiving it, I think, just because, rather than immersing himself wholly in the war, he has already attended to those existential layers that his fellow soldiers never notice.

About two-thirds of the way into the movie, when C-for-Charlie company has just ventured well inland to destroy a small contingent of Japanese soldiers, some of them reflect on what they have done. Corporal Fife (Adrien Brody) remembers a conversation in which another soldier told him that dead people were just like dead dogs. And then we see Witt staring intently at something. After a few seconds we are allowed to see what he sees: the half-buried face of a dead Japanese soldier.

And then the soldier (who is not a dead dog) speaks to him — speaks to the one person in this whole company who has been formed and equipped in such a way that he can hear. The Japanese soldier says:

Are you righteous? Kind? Does your confidence lie in this? Are you loved by all? Know that I was, too. Do you imagine your suffering will be any less because you loved goodness … truth?

And it is this revelation, I think, that enables Witt to do the great work of self-sacrifice that forms the climax of this film.