Like many of my posts, this one is a kind of sketch or draft of ideas I want to develop more fully later.

Last year I wrote a post about maps of Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, and mentioned in passing that the book’s scenes

veer from hard-coded allegory to plain realism, sometimes within a given sentence. One minute Moses is the canonical author of the Pentateuch, the next he’s a guy who keeps knocking Hopeful down. But the book is always psychologically realistic, to an extreme degree. No one knew anxiety and terror better than Bunyan did, and when Christian is passing through the Valley of the Shadow of Death and hears voices whispering blasphemies in his ears, the true horror of the moment is that he thinks he himself is uttering the blasphemies.

Bunyan always wants to present us with the most vivid representations possible of the various spiritual conditions within which we might dwell — but he’s an utter pragmatist about what representational mode best serves his purpose at any given moment.

This is just the sort of thing that Tolkien despised. He was so strict about following what he believed to be the rules of narration — absolute consistency (historical, physical, metaphysical, linguistic) within the frame of the writer’s “secondary world” — in his own stories that he just couldn’t understand other writers who didn’t feel the need. The appearance of Father Christmas in The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe made him apoplectic. Now, to be fair, that’s not CSL’s finest moment; but Tolkien failed to see that while consistency is a virtue in world-building it’s not the only virtue, and certain important effects, as we see from the example of Bunyan’s great story, can be created only by disregarding consistency.

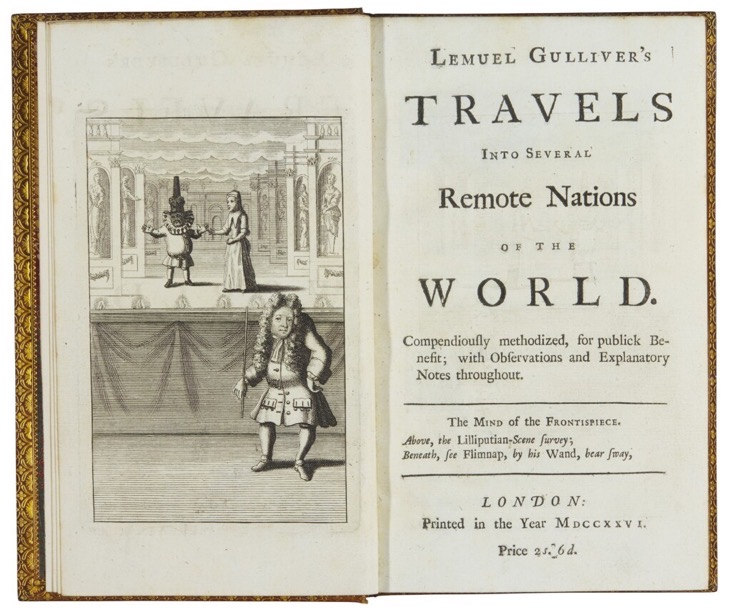

I’m thinking of these matters because right now I’m teaching Gulliver’s Travels, and Swift offers a master-class in the varying of representational modes. We all know that the book offers a satirical take on certain current events, but note the different ways British society is represented in the different Books.

Book I is fairly straightforward, especially in Chapter IV: the Lilliputians’ conflict with Blefuscu — the country from which they are separated by a narrow channel — over which end of an egg to crack is a simple (simplistic, I’d say) allegory of the mutual hatred of French Catholics (Big-endians) and English Protestants (Little-endians). Within Lilliput, the “two struggling parties in this empire, under the names of Tramecksan and Slamecksan, from the high and low heels of their shoes, by which they distinguish themselves” are (equally obviously) the High and Low Church parties.

But in Book II, Chapter VI we turn from allegory to realistic narration, as Gulliver eagerly and enthusiastically explains the political, legal, and economic system to the King of Brobdingnag — who, to Gulliver’s surprise and dismay, is not impressed. (“Yet thus much I may be allowed to say in my own vindication, that I artfully eluded many of his questions, and gave to every point a more favourable turn, by many degrees, than the strictness of truth would allow. For I have always borne that laudable partiality to my own country, which Dionysius Halicarnassensis, with so much justice, recommends to an historian: I would hide the frailties and deformities of my political mother, and place her virtues and beauties in the most advantageous light.”)

And then in Book III we’re back to allegory again, allegory indicated largely by anagrams and near-anagrams: Britain, or England, becomes “Tribnia, by the natives called Langden” — this preceding an attack on journalists and other writers. This diatribe, interestingly enough, is by Gulliver himself, and seems to indicate that some of the critiques of British society by the King of Brobdingnag have hit home. They come from Gulliver’s mouth now, though only in disguised form — as though his “laudable partiality to [his] own country” does not allow him to speak too straightforwardly.

And then of course in Book IV we get the apparently Utopian vision of the land of the morally and intellectually excellent Houyhnhnms and the disgusting Yahoos — the former being an allegorical representation of what humans might have been, the latter being a savagely realistic picture of us as we are…. At least, that’s what it looks like at first. Reflection complicates things. The Houyhnhnms’ moral excellence comes at a great cost: they cannot lie, but (per necessitatem) they also cannot imagine, cannot speculate, cannot explore. They can only receive what has been handed down to them by Tradition (it’s immensely significant that they are illiterate). What has been handed down is perfectly right … but the cost, the cost of it is high.

That’s a story for another day, though.

My chief point here: Swift’s representational modes are thus always shifting to meet the narrational and satirical needs of the moment. Tolkien wouldn’t have liked it, but it works. It’s a kind of narrational bricolage.