Our love is all of God’s money

What is money? Hard to say, really. It’s easier to document what it does, as Dana Gioia has shown:

It greases the palm, feathers a nest,

holds heads above water,

makes both ends meet.

Money breeds money.

Gathering interest, compounding daily.

Always in circulation.

“Circulation” is the key term here: money is always on the move, is always sliding from one location to another and then back to the first and then on to a third. People who work with money prize fluidity, because fluidity promotes circulation. And every development in computerized trading increases the speed of that circulation, so that now money moves faster than the human eye can see.

But the flow isn’t random, indeed is anything but random. Powerful gravity drags money towards other money. Think of how our solar system formed: the molecules that formed vast clouds of gas and dust drifted towards one another, forming clumps that attracted still more molecules, until eventually there condensed a star. That’s how money works. “Gathering interest, compounding daily.”

But, of course, as what is saved gathers interest, so too does what is owed. Money breeds money; debt breeds debt. And if not for debt, would money exist? “The first thing that happened in human history,” thinks a character in a new novel, “was not money, but debt – obligations and promises and duties incurred. Money arose only as a way of tabulating such owings.”

•

Most utopias and dystopias are concerned with money, and usually want to show the absurdity of it. This can be done whether a writer lives in an age of “Commodity Money” or “Representative Money” (to borrow terms from John Maynard Keynes). In Thomas More’s Utopia the shackles of prisoners are made from gold, so that that metal may be deposed; in Samuel Butler’s Erewhon the “Musical Banks” enact abstract rituals of circulation that are meant to remind us that the economy is a kind of religion and religion a kind of economy. In the most acute and insightful fictional exploration I know of these matters, Ursula K. LeGuin’s The Dispossessed, subtitled in some editions “An Ambiguous Utopia,” the culture of a capitalist planet is contrasted in vivid detail with that of an anarchist planet which has tried to eliminate money as best it can — but is left with other, less clearly defined, structures of circulation, ways for power and control to flow towards those who already have power and control.

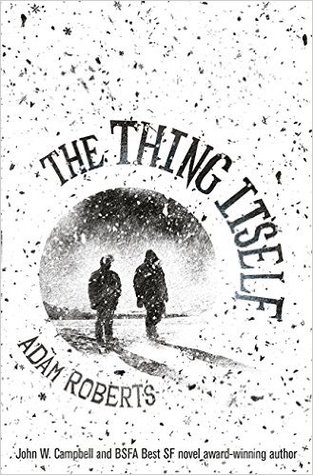

But LeGuin did not imagine a world in which near-instantaneous and near-universal digital communication enables money to do what it always wants to do. And here we turn to the novel I just quoted, Adam Roberts’s By the Pricking of Her Thumb.

Adam Roberts is a novelist of ideas, and I want to put equal stress on both of those terms: novelist, ideas. His books tend to be deeply reflective, serious and detailed and nuanced in their conceptual explorations, but those explorations are always embedded in really good stories — and cannot be simply extracted from those stories. That creates problems for someone who wants to write about his books without spoiling them for other readers. So if the discussion that follows is somewhat elliptical, that’s because I want you to read the book.

In this novel, four persons of great wealth have entered into an uneasy alliance in the hopes of achieving absolute wealth: to control nothing less than all the money in the world. The alliance is uneasy because the ultimate goal of each is to take everything from the others: to be the one rich person in a world of paupers, or at best dependents. The question is this: by what means might absolute wealth be acquired. The Fab Four have different ideas about that, and interestingly different ideas, but what they all come down to is this: seeking for ways to make every human relationship, every human desire, fungible — translatable into currency. One character here asks another, “You’re on the money can buy you love side of the debate?” And the other character answers: “I think love is the only thing money is any good for.”

But these Four are not the central figures in Roberts’s story, because the view from above does not interest him as much as the view from below. The protagonist of the book, a private investigator named Alma — she was also the protagonist of an earlier book, The Real-Town Murders — meets some of the Four, but her world could scarcely be more different from theirs. The flip side of absolute wealth is absolute precarity, and Alma is asymptotically approaching that even as the Four draw closer to their great goal. Increasingly Alma understands her life, and every aspect of her life, as shaped and formed by unpayable debts. Which means that the whole of her experience becomes a meditation on money — and its lack.

Grief, she saw now, was a mode of money. Death was a mode of money. Not, of course, the positive, cash-in-the-bank, the active fiction of money that the economic system painted so faux-optimistically. But that had never been the truth about money, had it? Money, by population mass, was debt, and debt was the key trope of negativity, and absence, and lack. Lack drove the economy, compelled people into work and ensured their persistence, lubricated the flow of capital and investment and liquidity. The whole system was a spider’s web stitched together, with a kind of tender fragility, over the empty mouth of debt, down which the wind was sucked.

All this is reminiscent of David Graeber’s 2012 book Debt: The First Five Thousand Years, and in that wide-ranging and fascinating book Graeber cites an anthropologist and former economist named Philippe Rospabé who makes the provocative comment that money arises “as a substitute for life.” If you give me life, if you sustain my life, if you save my life, I cannot replay you directly — cannot repay you in, as it were, the currency of the benefit you provided. Money, then, as Graeber puts the key point, “is first and foremost an acknowledgment that one owes something much more valuable than money.” John Ruskin famously wrote — a line cited in Roberts’s new novel — “There is no wealth but life,” which may well be true, but would equally be true to say that there is no debt but life.

•

In this morally fraught context, the very thing that makes money useful — its fungibility, its ability to be converted — abstracts it to some degree from our lifeworld. As our currency moves from (say) chickens to cowrie shells to gold coins to paper bills to binary digits readable on our smartphones, money extracts itself from its human context — it becomes in an eerily powerful sense autonomous.

In Charles Williams’s strange poetic sequence based on Arthurian legend, Taliessen through Logres, one poem describes King Arthur’s building of a mint and issuing of coins. “Kay, the king’s steward, wise in economics,” is pleased:

Traffic can hold now and treasure be held,

streams are bridged and mountains of ridged space

tunnelled; gold dances deftly across frontiers.

The poor have choice of purchase, the rich of rents,

and events move now in a smoother control

than the swords of lords or the orisons of nuns.

Money is the medium of exchange.

But Taliessen the poet is horrified: “I am afraid of the little loosed dragons” — the dragons, representing King Arthur Pendragon, stamped on the coins — because “When the means are autonomous, they are deadly.” The coins both represent the King and substitute for him: an abstract fungibility is meant to extend but ultimately threatens to replace the personal presence and authority of the monarch.

The Archbishop of Canterbury steps in and tries to pour oil on the troubled waters by demoting money, as it were: to Kay’s claim that “money is the medium of exchange” the Archbishop replies that “money is a medium of exchange.” The greater and more necessary currency is that of the circulation of gifts in Christian community, what Williams in his theological writings called the Way of Exchange: “dying each other’s life, living each other’s death.” The Archbishop’s speech is a nice little exercise in peacemaking, as perhaps is fitting the episcopal role, and it clearly attempts to incorporate Jesus’s bizarre commandment to his disciples to “make friends for yourselves by means of dishonest wealth so that when it is gone, they may welcome you into the eternal homes”; but such splitting-the-difference is perhaps too easy. It assumes that money can be constrained to accept its place as a secondary medium of exchange, subservient to the greater authority of charity. But Taliessen’s fear of what happens when the means become autonomous seems to me a well-warranted fear.

Which brings us back to By the Pricking of Her Thumb. The book concerns itself with many things — love and loss; the difference between “real life”and an increasingly compelling online world; the films of Stanley Kubrick — but the central and compelling concept is this: what if the long-promised Singularity comes, or something rather like it, and what has become self-aware is simply … money itself? What if our future is a future of, in the strongest sense possible, Smart Money?

It really and truly doesn’t bear thinking of. After all, money is powerful enough, influential enough, near-sentient enough, as it is already. As Gioia writes,

Money. You don’t know where it’s been,

but you put it where your mouth is.

And it talks.

Well, one thing led to another, so… The place:

Well, one thing led to another, so… The place: