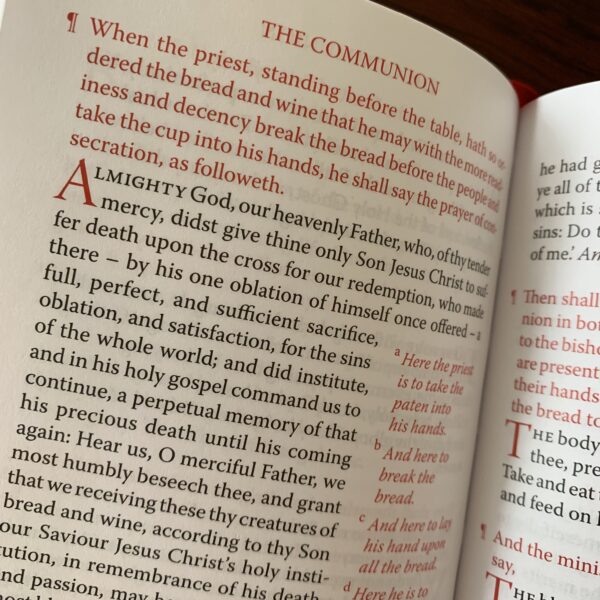

The Scriptural Book of Common Prayer is a wonderful resource that does its job a little too well. That job is to lead readers to the biblical sources that underlie almost every phrase in the prayer book. But some biblical sources are more important than others.

The famous first line of the Collect for Purity is: “Almighty God, unto whom all hearts be open, all desires known, and from whom no secrets are hid….” At the Scriptural BCP page, if you click on that line, here’s what you get:

Gen 17:1 When Abram was ninety-nine years old, the Lord appeared to Abram, and said to him, “I am God Almighty; walk before me, and be blameless.

1 Sam 2:3 Talk no more so very proudly, let not arrogance come from your mouth; for the Lord is a God of knowledge, and by him actions are weighed.

1 Kings 8:39 then hear in heaven your dwelling place, forgive, act, and render to all whose hearts you know–according to all their ways, for only you know what is in every human heart—

1 Chron 28:9 “And you, my son Solomon, know the God of your father, and serve him with single mind and willing heart; for the Lord searches every mind, and understands every plan and thought. If you seek him, he will be found by you; but if you forsake him, he will abandon you forever.

Job 42.4 ‘Hear, and I will speak; I will question you, and you declare to me.’

Ps 38:9 O Lord, all my longing is known to you; my sighing is not hidden from you.

Ps 44:21 would not God discover this? For he knows the secrets of the heart.

Ps 139:1-4 O Lord, you have searched me and known me. You know when I sit down and when I rise up; you discern my thoughts from far away. You search out my path and my lying down, and are acquainted with all my ways. Even before a word is on my tongue, O Lord, you know it completely.

Jer 17:10 I the Lord test the mind and search the heart, to give to all according to their ways, according to the fruit of their doings.

Ezek 11:5 Then the spirit of the Lord fell upon me, and he said to me, “Say, Thus says the Lord: This is what you think, O house of Israel; I know the things that come into your mind.

Matt 12:25 He knew what they were thinking and said to them, “Every kingdom divided against itself is laid waste, and no city or house divided against itself will stand.

John 2:24-25 But Jesus on his part would not entrust himself to them, because he knew all people and needed no one to testify about anyone; for he himself knew what was in everyone.

1 Cor 3:20 and again, “The Lord knows the thoughts of the wise, that they are futile.”

Heb 4:13 And before him no creature is hidden, but all are naked and laid bare to the eyes of the one to whom we must render an account.

Rev 3:1 “And to the angel of the church in Sardis write: These are the words of him who has the seven spirits of God and the seven stars: “I know your works; you have a name of being alive, but you are dead.

Rev 3:8 “I know your works. Look, I have set before you an open door, which no one is able to shut. I know that you have but little power, and yet you have kept my word and have not denied my name.

Rev 3:15 “I know your works; you are neither cold nor hot. I wish that you were either cold or hot.

Acts 1:24 Then they prayed and said, “Lord, you know everyone’s heart. Show us which one of these two you have chosen.”

Just having so many sources listed is daunting. And some of them, like the passage from Job, seem unrelated to the collect, while others (1 Samuel 2:3, and the passages from Revelation, which are about our works, not our heart) are only tangentially related at most. I think all this might be more useful — especially for people new to the prayer book, or new to the Bible — if the references were confined to the essential ones.

Nevertheless: a wonderful resource, and a testament to how skillfully and sensitively Thomas Cranmer and the other authors of the prayer book wove the words of Scripture into their liturgies.