I haven’t forgotten about middlebrow matters, but right now my mind is on something else. Something related, though.

Readers of Gaudy Night (1935) will recall — stop reading if you haven’t read Gaudy Night and don’t want any spoilers — that the plot hinges on an event that occurred some years before the book’s present-day: a (male) historian fudged some evidence and a (female) historian caught him at it and reported the malfeasance, which led to his losing his job. Late in the book, but before the full relevance of this event to the plot has been revealed, there’s a conversation about scholarly integrity, which I will now drop into the middle of:

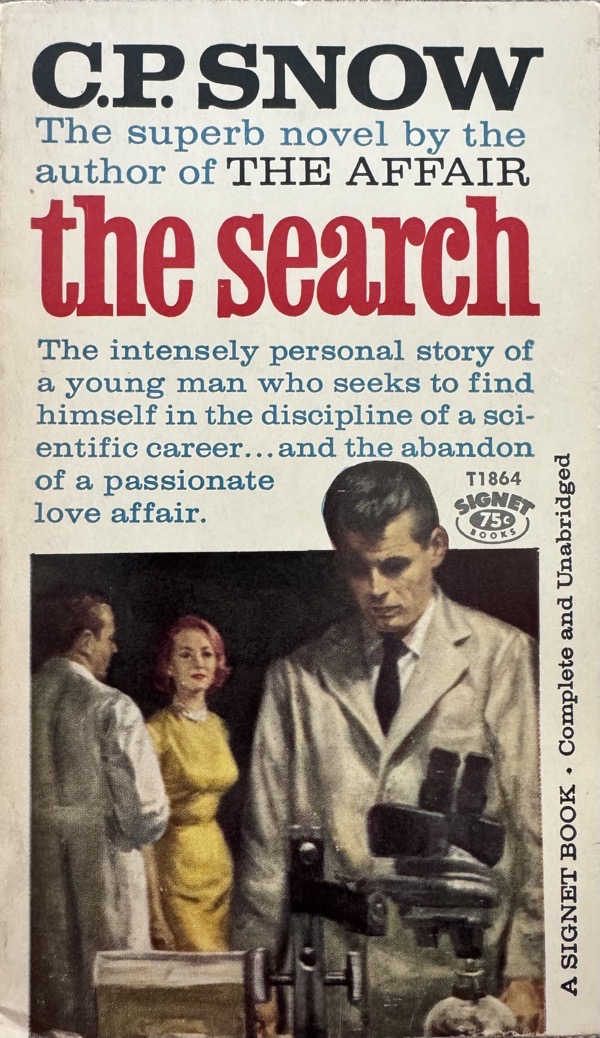

“So long,” said Wimsey, “as it doesn’t falsify the facts. But it might be a different kind of thing. To take a concrete instance — somebody wrote a novel called The Search — “

“C. P. Snow,” said Miss Burrows. “It’s funny you should mention that. It was the book that the — ”

“I know,” said Peter. “That’s possibly why it was in my mind.”

A person has been vandalizing Shrewsbury College and a copy of that novel, with certain pages torn out, has been found. The novel, by the way, appeared in 1934, around the time that Sayers began writing Gaudy Night. It would be interesting to know whether it was the direct inspiration for her story, or whether she read it after some elements were already in place. I hope to find out more about that.

And by the way, I am going to be spoiling that novel far more thoroughly than I will spoil Gaudy Night — but it’s not one that many people read, these days.

“I never read the book,” said the Warden.

“Oh, I did,” said the Dean. “It’s about a man who starts out to be a scientist and gets on very well till, just as he’s going to be appointed to an important executive post, he finds he’s made a careless error in a scientific paper. He didn’t check his assistant’s results, or something. Somebody finds out, and he doesn’t get the job. So he decides he doesn’t really care about science after all.”

“Obviously not,” said Miss Edwards. “He only cared about the post.”

Neither the Dean, who has read the book, nor Miss Edwards, who hasn’t, is quite accurate. The scholar, whose name is Arthur Miles, probably would have gotten the post even without the paper; but it’s perfectly possible that he rushed the paper, failed to be appropriately self-critical, because he knew that the vote for the Director of a new scientific institute would be coming soon. Miles doesn’t know; he can’t be sure; maybe he would’ve made the mistake anyway. But in any case, as soon as he is told that there’s a problem with his paper, he runs the numbers again, sees the error, and immediately admits that he was wrong.

Let me pause for two digressions:

- Sayers specifies what pages were torn from the book — but I don’t have access to the edition that Sayers had read, which I assume was the first hardcover edition, so I don’t know what exactly was excised, but I suspect that it was the part where Miles admits his mistake. (The whole business is a flaw in Sayers’s plot, because it’s impossible to imagine the Responsible Party having read Snow’s book and known which pages to tear out; but DLS clearly was determined to get a discussion of The Search into her own novel, so she found a way.)

- As it happens, this is Snow’s most autobiographical novel: what happened to Miles also happened to him. He began his career as a chemist, and wrote a paper (published in Nature) which was then discovered to contain an embarrassing mistake — upon which he abandoned his work as a scientist and became a novelist and bureaucrat.

Now, back to Gaudy Night:

“The point about it,” said Wimsey, “is what an elderly scientist says to him. He tells him: ‘The only ethical principle which has made science possible is that the truth shall be told all the time. If we do not penalize false statements made in error, we open up the way for false statements by intention. And a false statement of fact, made deliberately, is the most serious crime a scientist can commit.’ Words to that effect. I may not be quoting quite correctly.“

Wimsey’s summary is a good one. This is indeed what the “elderly scientist,” a man named Hulme, says to him. And Miles does not disagree. What’s more on his mind, though, is the picture of his future laid out for him by another senior scientist:

“You’ve got to work absolutely steadily, without another suspicion of a mistake. You’ve got to let yourself be patronised and regretted over. You’ve got to get out of the limelight. Then in three or four years, you’ll be back where you were; though it will be held up against you, one way and another, for longer than that. It will delay your getting into the Royal [Society], of course. That can’t be helped. You’ll have a lean time for a while; but you’re young enough to get over it.”

Faced with this prospect, Miles realizes that he could only manage all this (“Watching the dullards gloat. Working under Tremlin. Having every day a reminder of the old dreams”) if he had a genuine devotion to science. But: “It occurred to me I had no devotion to science.”

N.B.: the point is not that the event has taken away his devotion to science, but rather, “I am not devoted to science, I thought. And I have not been for years, and I have kept it from myself till now.” The revelation of his error leads to a revelation of what had been true about him all along: “There were so many signs going back so far, if I had let myself see, if it had been convenient to see.” Indeed, it now becomes clear to him that his desire to become the director of a scientific institute — an administrative position, not one that would involve him directly in research — precisely because on some unconscious level he didn’t want to be a scientist any more: “I had thrown myself into human beings — to escape the chill when my scientific devotion ended.”

It should be clear, then, that “he decides he doesn’t really care about science after all” is not an adequate explanation of what happens.

But there’s also a twist in the tail of this story, which in Gaudy Night Sayers calls attention to:

“In the same novel,” said the Dean, “somebody deliberately falsifies a result — later on, I mean — in order to get a job. And the man who made the original mistake finds it out. But he says nothing, because the other man is very badly off and has a wife and family to keep.”

”These wives and families!“ said Peter.

”Does the author approve?“ inquired the Warden.

”Well,“ said the Dean, ”the book ends there, so I suppose he does.”

Or does he? And is that an accurate description of the case? Several facts here are relevant:

- The man who has falsified the data, Sheriff, is one of Miles’s oldest friends.

- Miles got Sheriff his current job and has been guiding his research, trying to keep him on the straight and narrow — he’s a feckless fellow, and a habitual liar, but Miles had hoped that he was ready to reform.

- Sheriff had promised Miles, and also his own wife, that he was working on a safe project when he was in fact working on a high-risk, high-reward one — one he thought likely to lead to a prestigious position that, now that the paper has been published, he is indeed about to be offered.

- Miles has a sense of responsibility for Sheriff because he had hoped to hire him for a position at the aforementioned Institute, but gave up on the idea when he realized that his own position was compromised. He thinks perhaps he should have pushed harder for Sheriff anyway.

- Early in his career Miles had had the opportunity to consciously fudge data himself, and seriously considered it — he thought that he might eventually be found out, but only after achieving a brilliant career from which summit he could just say “Whoops, I made a mistake” — but instead abandoned the research project. He thought, though, that in the future he would have compassion for any scientist who succumbed to a similar temptation.

- And most important of all, Sheriff is married to Audrey, Miles’s former lover, for whom, though he himself is now happily married, he cherishes a strong and lasting tendresse — despite the fact that Sheriff basically stole her affections while Miles was abroad.

The Search is not a great novel, but this is perhaps its best element: the faithful portrayal of Miles’s complex and ever-shifting and deeply human responses to Sheriff’s lying. (It reminds me a bit of the greatest scene of this kind I know, the moment in Middlemarch when Lydgate has to decide how to vote for the chaplaincy of a new hospital. I wrote about that thirty years ago [!!] near the end of this essay.)

On the one hand, he knows exactly what Sheriff did and why:

I had no doubts at all. It was a deliberate mistake. He had committed the major scientific crime (I could still hear Hulme’s voice trickling gently, firmly on).

Sheriff had given some false facts, suppressed some true ones. When I realised it, I was not particularly surprised. I could imagine his quick, ingenious, harassed mind thinking it over. For various reasons, he had chosen this problem; it would not take so much work, it would be more exciting, it might secure his niche straight away. … But I must not know, half because he was a little ashamed, half because I might interfere. So [his research assistant] and Audrey must, for safety’s sake, also be deceived.

All this he would do quite cheerfully. The problem began well. … Then he came to that stage where every result seemed to contradict the last, where there was no clear road ahead, where there seemed no road ahead at all. There he must have hesitated. On the one hand he had lost months, there would be no position for years, he would have to come to me and confess; on the other his mind flitted round the chance of a fraud.

There was a risk, but he might secure all the success still. I scarcely think the ethics of scientific deceit troubled him; but the risk must have done. For if he were found out, he was ruined. He might keep on as a minor lecturer, but there would be nothing ahead.

Miles does not excuse Sheriff at any point; he knows that the man’s dishonesty is habitual, perhaps pathological. But he also knows that Sheriff and Audrey have reached a certain accommodation in their marriage, that Audrey understands who her husband is but loves him and needs him anyway. Miles writes a letter that would expose and run Sheriff, and then, realizing that it would also ruin Audrey, …

I shall not send the letter, I was thinking. Let him win his gamble. Let him cheat his way to the respectable success he wants. He will delight in it, and become a figure in the scientific world; and give broadcast talks and views on immortality; all of which he will love. And Audrey will be there, amused but rather proud. Oh, let him have it.

For me, if I do not send the letter, what then? There was only one answer; I was breaking irrevocably from science. This was the end, for me. Ever since I left professionally, I had been keeping a retreat open in my mind; supervising Sheriff had meant to myself that I could go back at any time. If I did not write I should be depriving myself of the loophole. I should have proved, once for all, how little science mattered to me.

There were no ways between. I could have held my hand until he was elected, and then threatened that either he must correct the mistake, or I would; but that was a compromise in action and not in mind. No, he should have his triumph to the full. Audrey should not know, she had seen so many disillusions, I would spare her this.

The human wins out over the scientific. Maybe, Arthur thinks, it always does. But Gaudy Night shows that sometimes the scientific — in the sense of a strict commitment to the sacredness of honest research — can sometimes have its own victories. And Gaudy Night also suggests that the choices might not be as stark as Snow’s story suggests. More on that in another post.