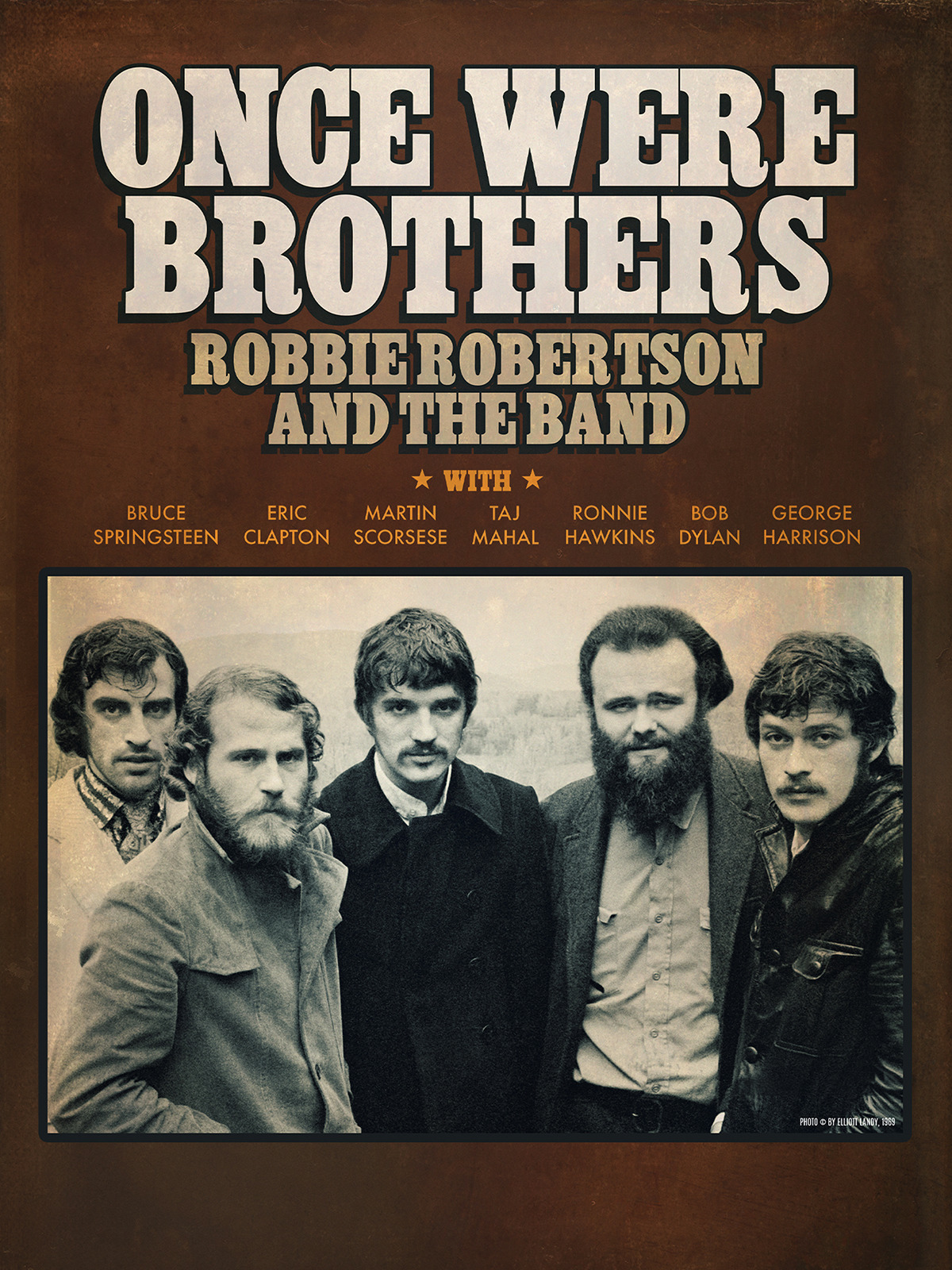

The fascinating and deeply sad documentary Once Were Brothers concerns the career of The Band — primarily as seen through the eyes of Robbie Robertson. Levon Helm, dead lone before the documentary was made, would have told a rather different story, and for damn sure wouldn’t have subtitled the movie “Robbie Robertson and The Band.” For Levon they were always The Band, five equal partners. But that’s a debate for another day.

In the documentary, the one song that gets the most attention is “The Weight.” And for good reason. It was a step forward for Robertson as a songwriter – there’s a touching moment when he describes playing it for Dylan and notes how proud Dylan was of him. You can tell that that pride meant a lot to Robbie. But it was also a step forward for The Band. In an old interview clip Richard Manuel says that in making that song “we found a vocal thing that we didn’t know we had,” and he’s surely talking primarily about the harmonies on that song, especially the rising “and-and-and” at the end of each chorus. (There’s a great passage in Mystery Train where Greil Marcus recalls living in San Francisco when Music from Big Pink was released: “The day after the record hit the stores you could hear people on the street singing the chorus to ‘The Weight’; before long, the music became part of the fabric of daily life.”)

Elsewhere in the documentary Bruce Springsteen marvels at the presence in a single group of three singers as extraordinary as Manuel, Levon, and Rick Danko; and George Harrison muses on the boon to a songwriter of being able to compose for such singers, knowing that any given song might be a better fit for one than for the others. But the three voices complemented one another so beautifully, with Danko as an absolute master of bluegrass-style high harmony singing, Levon somewhere in the middle, and Manuel able to go high or low as the situation demanded. (One of the amazing things about “The Weight” is that, right in the middle of the song, Danko picks up the lead vocal from Levon — and it sounds fantastic.)

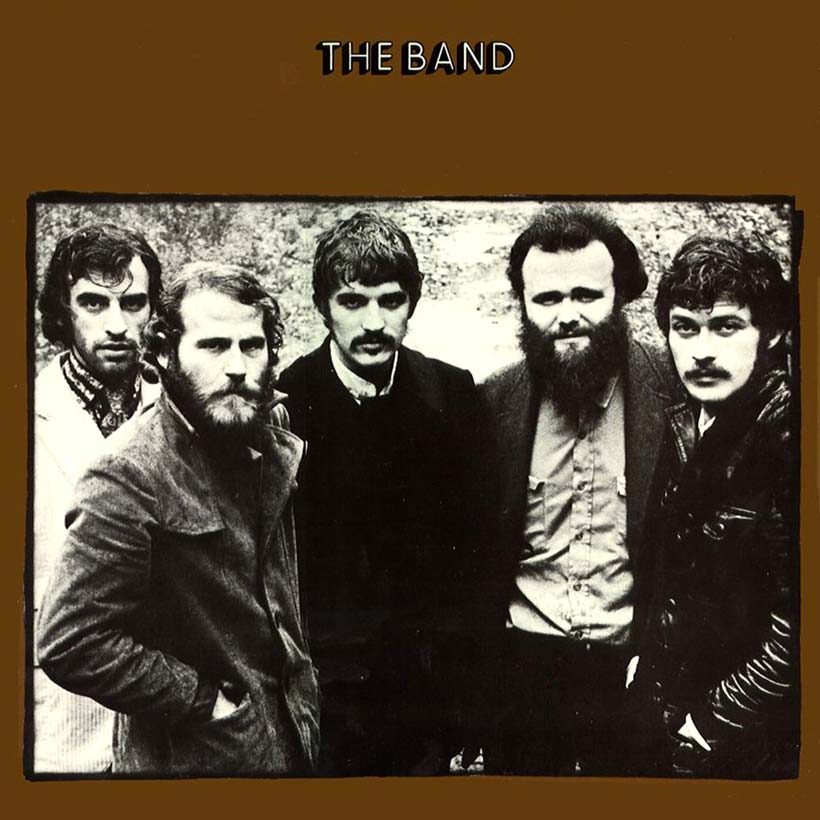

So “The Weight” was the moment The Band discovered what it could do in songwriting and singing, and maybe arranging as well. Soon after recording Music from Big Pink Danko broke his neck in a car accident and was immobile for quite some time, so instead of going on tour the guys continued to hang out in Woodstock and made another record: The Band, or, as it’s commonly known, the Brown Album. And this is when they put into practice everything they learned when making their first album; this is when they came into their inheritance.

It’s an astonishing record, in my view one of the half-dozen best in the history of rock music. Not one song is anything less than superb — and that makes it different than any of their other albums, including Big Pink, all of which are very much hit-and-miss. Nothing else they ever did comes close to this masterpiece.

I have occasionally referred to a distinction made by Bill James in his work on evaluating the quality of baseball players: career value vs. peak value. How do you compare a player like (for example) Eddie Murray, who was a superb if not absolutely great player for a very long time, with Pete Reiser, who was transcendently great but (because of injuries) only for a short time? Similarly: The Band’s career value can’t compare with that of U2 – but no rock group’s peak value has ever been higher.

Did it have to be that way? Did they just have it in them to make one great album? Sometimes that’s all a group, or a musician, has. But I think they were so deeply immersed in what Dylan used to call “historical-traditional music” that they could have and should have produced much more excellent work. Drugs did them in, frankly, and in an especially ugly way.

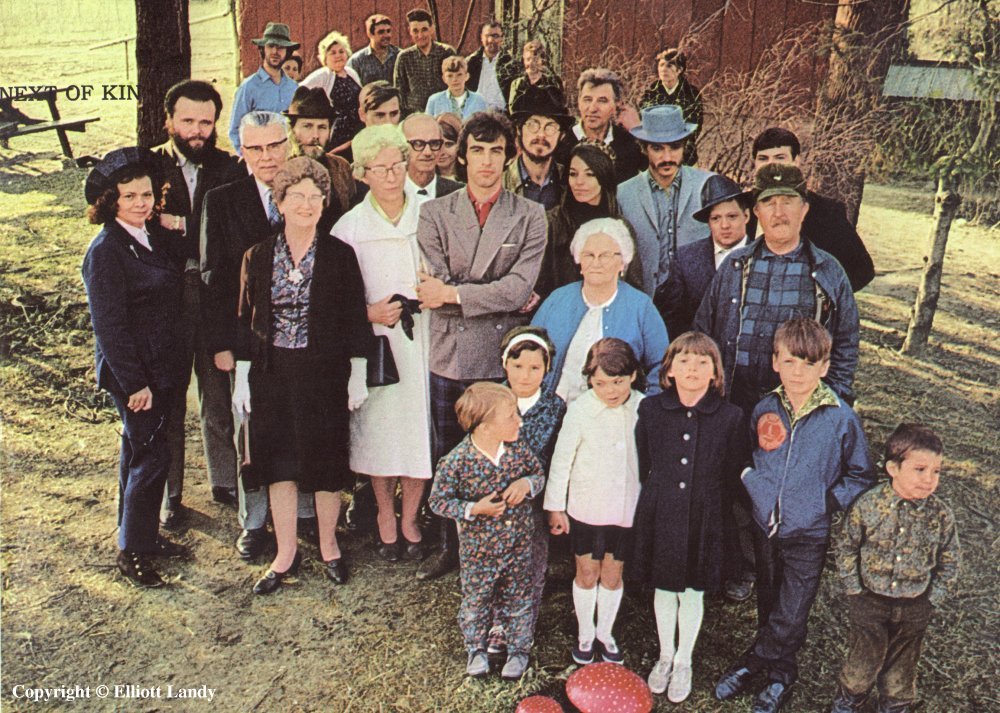

In Once Were Brothers we hear from the wonderful photographer Elliot Landy, who did so much to document life in Woodstock in those days. What struck him is how “grounded” the members of The Band were, how “gracious” — the way country people are gracious, he said. He was taken with their evident love for one another, and — here I think of something Robbie said somewhere else, that “We were rebelling against the rebellion” — their determination to put a photo of their families in the album gatefold.

Yet they came to hate one another, or something close to hate. When two guys (Robbie and Garth Hudson) are coming to work every morning while the other three are in bed till mid-afternoon, sleeping off the previous night’s festivities … well, that’s not a recipe for fellow-feeling. Robbie loved Richard Manuel – everybody seems to have loved him – but when Manuel insisted on driving while dead drunk, with Robbie’s wife Dominique in the car, and then crashed it…. “Richard could’ve killed my wife,” Robbie says in the documentary — not angrily, but, the point is, that’s not something you easily forget, easily set aside. And there were many such events in Woodstock in those days.

My suspicion is this: if they had stayed off the drugs, or even kept their use to a reasonable level, then I think we would have gotten much more great music from The Band. And then maybe some guys who really loved one another would have had friendships to sustain them in their later years. As I say, it’s a deeply sad story.