The Writer’s Map An Atlas of Imaginary Lands edited by Huw Lewis-Jones Chicago, 256 pp., $45

This review originally appeared in The Weekly Standard (November 04, 2018)

Barring some unforeseen miracle of publishing occurring in the next few weeks, The Writer’s Map will be my book of the year for 2018. It gathers intelligently charming meditations from writers and festoons them with map after map after map after map of imaginary, and sometimes non-imaginary, lands. (Only after several days of staring at the beautifully reproduced images did I force myself to read the words, but I am glad I finally did.) I am so enamored of this book that I bitterly resent what takes me away from it, whether that be the need to eat, or sleep, or write this review. But when duty calls, I sometimes answer.

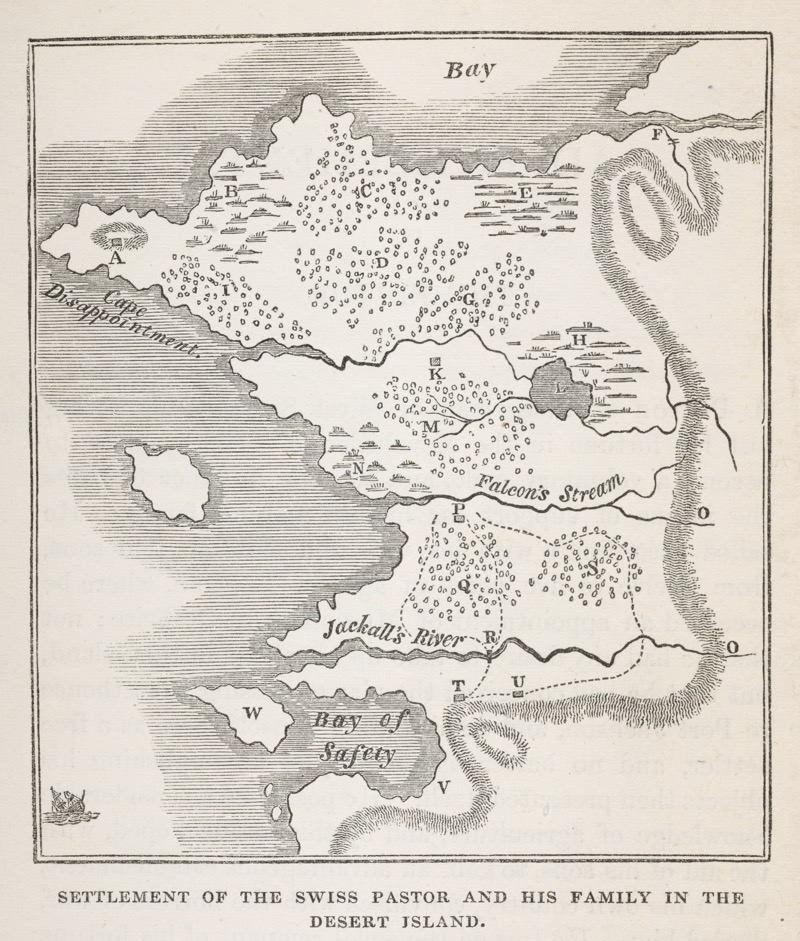

Map of New Switzerland, the settlement farmed into existence by the Swiss Family Robinson. British Library, London, via University of Chicago Press

The love of maps is widespread, but not all of us love them for the same reasons. Marlow, the narrator of Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, traces his career as a sailor to a love of maps:

Now when I was a little chap I had a passion for maps. I would look for hours at South America, or Africa, or Australia, and lose myself in all the glories of exploration. At that time there were many blank spaces on the earth, and when I saw one that looked particularly inviting on a map (but they all look that) I would put my finger on it and say, “When I grow up I will go there.”

For me maps have almost the opposite effect: They make me glad that I can see so much while staying home. (This tendency has only strengthened as air travel has become more unpleasant.) In his prologue to this volume, Philip Pullman explains one source of the pleasure I feel:

I first learnt how to make a map at the age of about eight, when our teacher showed us how to pace out the length and breadth of the school playground and draw it on paper. Such power! To see things as if from above, and to make different sorts of marks on the paper to show trees, and rivers, and walls and buildings.

Indeed, “to see things as if from above”: to take in a landscape with a glance, to see its bones as well as its flesh, to perceive what the poet Gerard Manley Hopkins called its “inscape,” the distinctive frequency at which its nature vibrates. I have a sense, looking at an excellent map, that I see something about a place that cannot be seen from ground level. Certain distinctive kinds of story emerge from certain landscapes: Things happen in the mountains that can’t happen on the plains, in an ancient city that can’t happen in a new one. Maps reveal this to us all at once. The novelist David Mitchell spent much of his childhood making maps, only later deciding what stories they contained; and to this day he makes similar sketches when writing his novels.

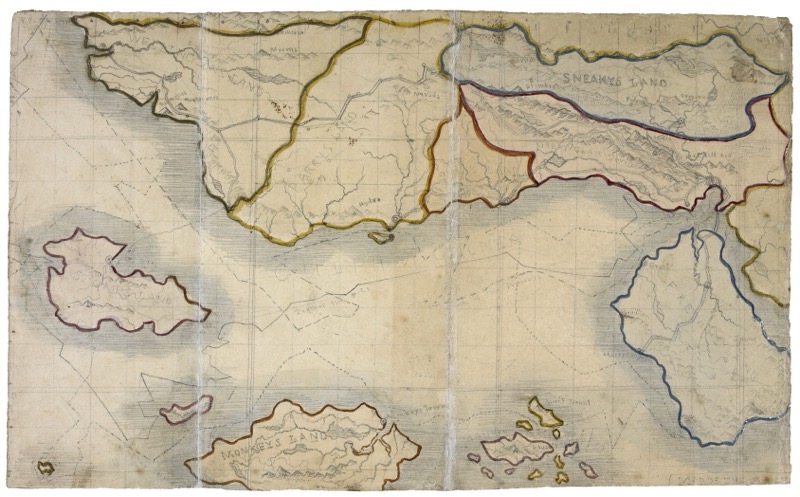

A map drawn by Branwell Brontë depicting imaginary realms — Sneakys Land, Monkeys Land, and others — dreamed up by his sister Charlotte in 1826. British Library, London, via University of Chicago Press

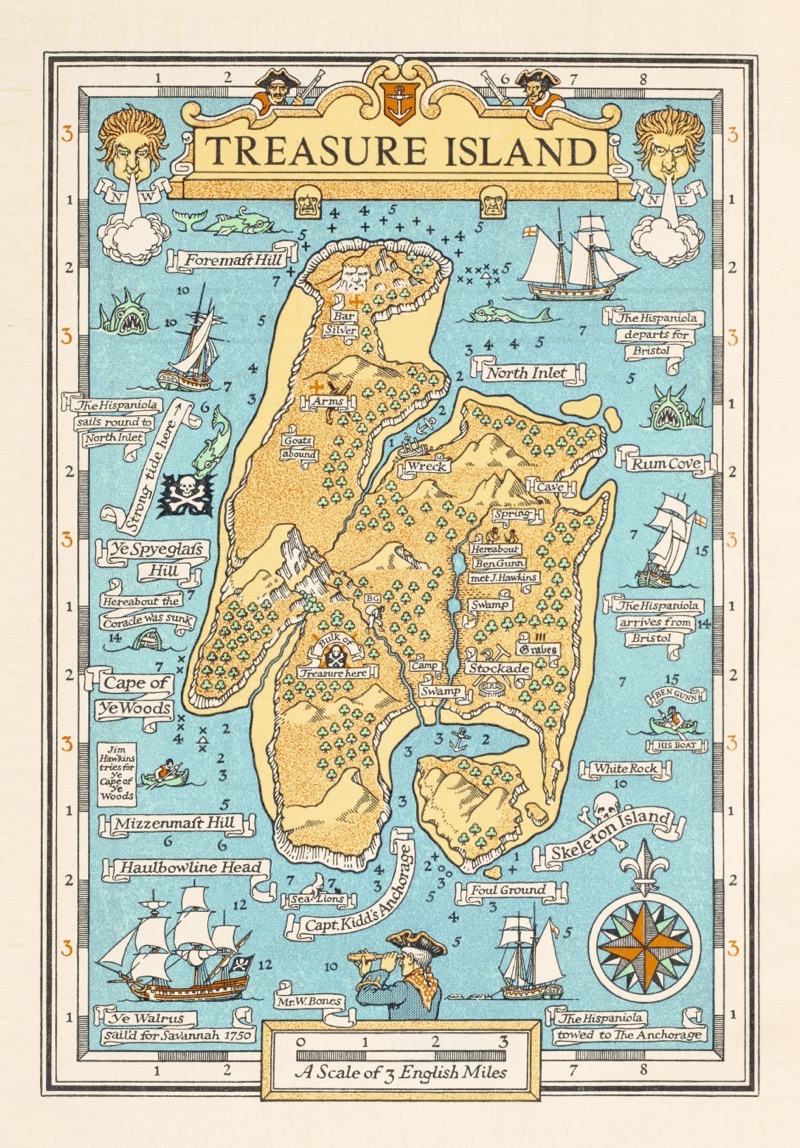

That connection between imaged place and story is a key reason why, as Robert Macfarlane convincingly suggests in his contribution to The Writer’s Map, the best maps are of islands. Helen Moss would agree. Remembering her childhood, she writes, “No imaginary friends for me; I could never get the hang of them. It was imaginary islands every time.” During the rainy Scottish summer of 1881, Robert Louis Stevenson made an elaborate (and very skillfully drawn!) map for his stepson, and from that map emerged, inevitably it seems, the story called Treasure Island. The whole tale was implicit in the shape of the place, and when no other places are on the map that kind of thing can be more easily seen.

A map by the Scottish illustrator Monro Orr to accompany a 1934 edition of Robert Louis Stevenson’s ‘Treasure Island.’ British Library, London, via University of Chicago Press

This is true even when places aren’t literally islands but are self-contained to a degree that nothing outside their boundaries is effectively real. A.A. Milne’s Hundred Acre Wood might as well be an island, as might Trollope’s Barsetshire, Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha County, and Richard Adams’s Watership Down. (Adams knew from the beginning the boundaries of his locale, because it is a real place, but Trollope and Faulkner only started making maps when they were well into their storytelling and had begun to be confused.)

Macfarlane tells us that “the Inuit people are also known to have carved three-dimensional maps of coastlines from wood. In this way, the maps were portable, resistant to cold, and, if they were dropped into water, would float and could be retrieved.” This is admirable, and it occurs to me that one could do this for the whole world; perhaps the resulting object could be called a “globe.” But the flatness of maps is, for me, key to their charm, because of the way flatness enables distinctness while requiring imagination. And my very favorite maps appear as the endpapers of books. Several of those are reproduced in The Writer’s Map, including those from Graham Greene’s Journey Without Maps, Malcolm Saville’s Mystery at Witchend, and a book adapted from the British TV series Ivor the Engine (featuring a exceptionally lovely map, by Peter Firmin, of the Merioneth and Llantisilly Railway, located in “the top left-hand corner of Wales”). There is something wonderfully daydream-conducive about being able to pause in the midst of a narrative and flip instantly to the two-dimensional representation of the world you are inhabiting, especially when that representation surrounds and encloses the fictional world.

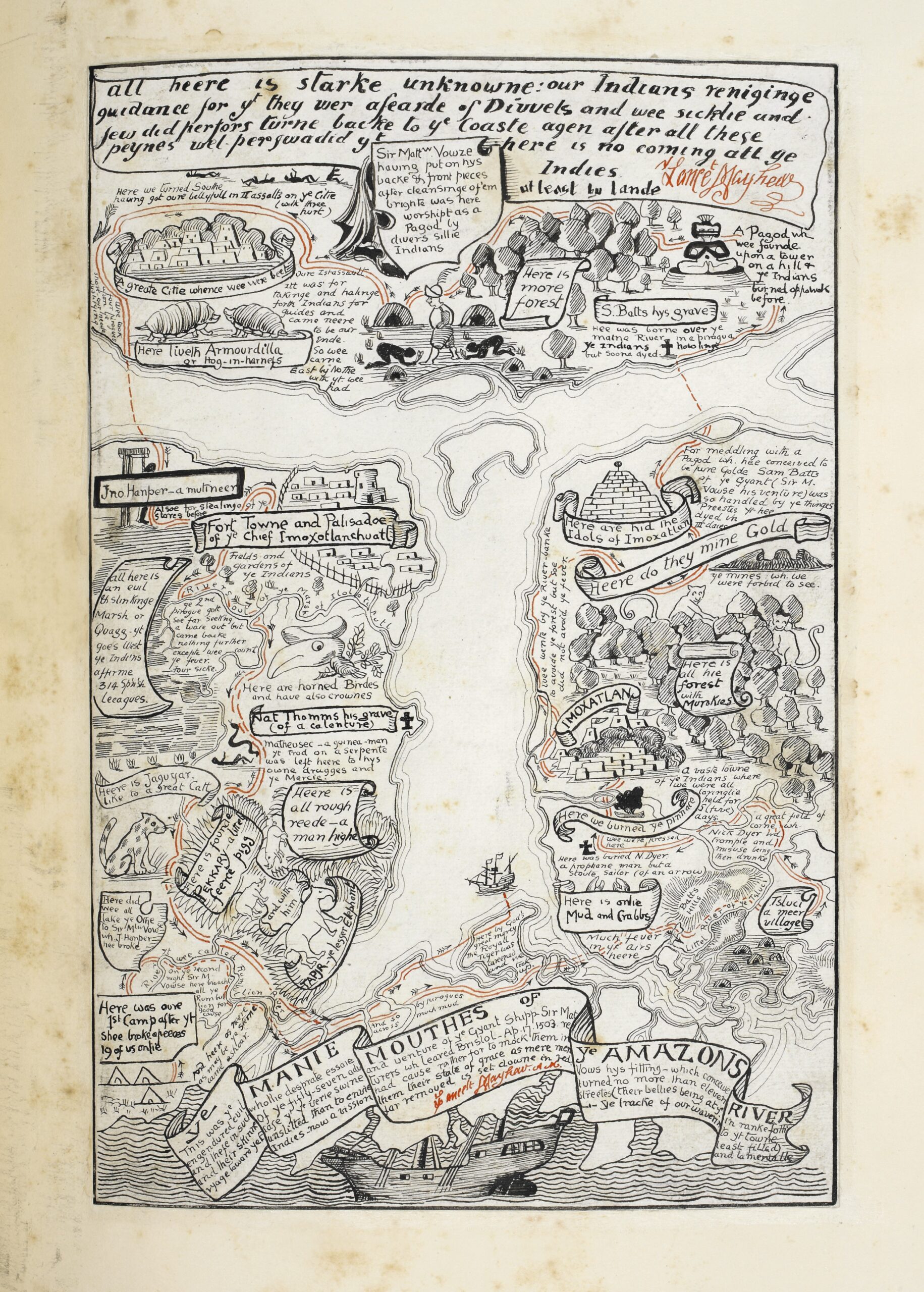

A map made by Rudyard Kipling to appear with “The Beginning of Armadillos” in his ‘Just So Stories’ (1902). British Library, London, via University of Chicago Press

But maybe the Inuit were on to something as well. One of the most delightful chapters in The Writer’s Map is by Miraphora Mina, who designed an especially important map for the Harry Potter movies. In the books, the Marauder’s Map—created by Messrs. Moony, Wormtail, Padfoot, and Prongs—is a simple folded piece of parchment that can be opened with a tap of a magic wand and the incantation “I solemnly swear that I am up to no good,” and in that opened state reveals the whereabouts of every single person in Hogwarts Castle. One sees their names gliding through the hallways or remaining motionless in an office or bedroom. The map can be sealed from prying eyes simply by closing it, tapping it again, and murmuring the phrase “Mischief managed.”

But Mina seems to have realized that the four Marauders created something that tends to blur the lines between the map and what it represents, and for this reason she made a very elaborate map indeed, something approaching the character of a pop-up book, with multiple layers of flaps and an extensive repertoire of accordion-like unfoldings. The world the map describes comes alive, it rises out of the map and demands our attention. When I first saw her work, in Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban, I laughed out loud and desperately wanted one of my own.

Mina says that for her “the best stories are those where real and imaginary places are constantly overlapping, colliding perhaps, the fantasy and the everyday”; she further suggests, “Mapmaking is often like this. It’s a daily process of managing mischief—overcoming dangers, problems, half-truths, illusions, deadlines and distractions—and tiptoeing along the edges of the known while also opening up new realms for adventure.” This happens to be a very neat description also of the images in The Writer’s Map and their complex relationship to the stories that they emerge from or that emerge from them.

And now, duty done, mischief managed, I plunge back into this delightful world of imaginary worlds. Please do not interrupt me again.