A while back I commented on a post by Robin Sloan in which he says this:

Sometimes I think that, even amidst all these ruptures and renovations, the biggest divide in media exists simply between those who finish things, and those who don’t. The divide exists also, therefore, between the platforms and institutions that support the finishing of things, and those that don’t.

Finishing only means: the work remains after you relent, as you must, somehow, eventually. When you step off the treadmill. When you rest.

Finishing only means: the work is whole, comprehensible, enjoyable. Its invitation is persistent; permanent.

I like this, but I want to make a distinction between resting from your labors on a particular project and resting from your labors altogether, through retirement or death.

My attitude toward the works I have completed — at at this point that’s fifteen books and a couple of hundred essays and reviews — is that I have never finished anything to my own satisfaction, I have only been forced to abandon it. That’s why I am psychologically incapable of re-reading anything I’ve written. I may retrieve small chunks of it for one purpose or another, but I’ve never re-read anything of mine longer than a blog post. I learned early in my career that revisiting what I’ve published brings only regrets. So, you know, as the man said: “Fare forward, voyagers.”

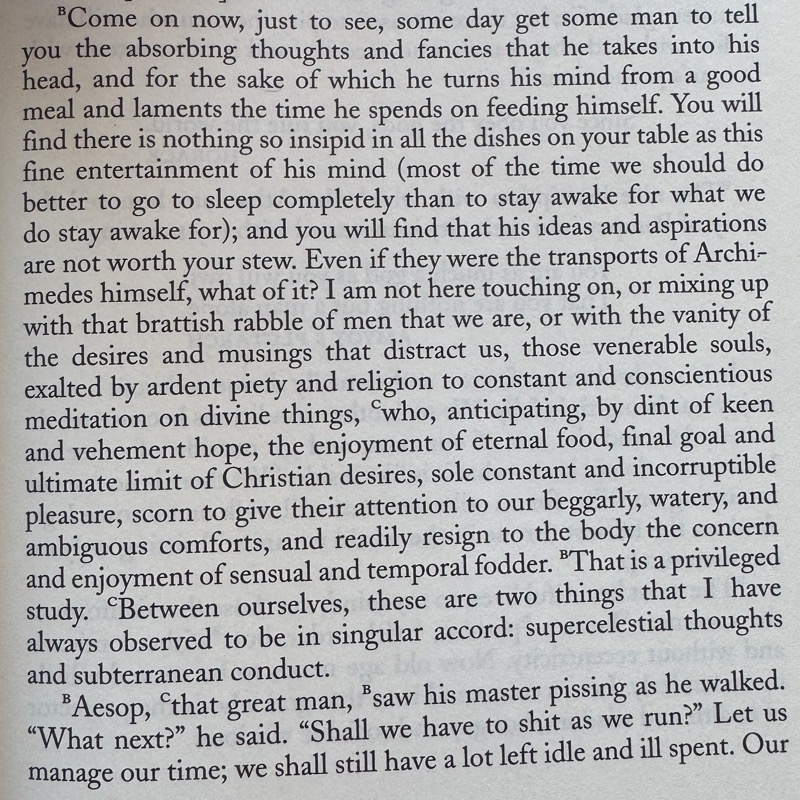

Maybe for this reason I am drawn toward the work that is never finished in the sense that it’s never handed over to someone else, never designated as complete. Take Montaigne’s Essays for instance, a page of which, in a modern edition or translation, looks like this:

Montaigne published the first edition of the Essays in 1580 – that’s the main text here. Then in 1588 he published a second edition with new essays and revisions to the earlier ones: those are marked [b]. He continued up to the end of his life to add new essays and revise the old ones: those most recent changes are marked [c]. Montaigne died at age 59, but if he had lived twenty years longer we might have had further editions of the Essays and, consequently, texts with markings of [d], [e], and [f].

I love this. “Essay” means “trial” or “attempt,” of course, and thus Montaigne’s book by its very nature invites second and third thoughts, second and third trials: iteration that ends only when you die, or when you grow tired of it all and retreat into a life of pure contemplation.

I’m a big fan of contemplation, but I tend to contemplate most effectively when I have a pen in my hand. And a notebook provides endless opportunities to revisit, rethink, fail again, fail better. Though I never re-read my published works, I re-read my notebooks regularly: I consider such revisitations essential to thought, to growth, to intellectual and moral and spiritual maturation.

For me — for my personal wants and needs and satisfactions — my notebooks are the most important writing I do. Then come my essays, and then my books. I think I have written some good books, and they’re made a place for themselves in the world — I’ve sold about 300,000 copies all told, most of those The Narnian and How to Think, which is nothing compared to having a YouTube channel, but not altogether contemptible for a writer of books — but if I had not been in a profession that places a premium on the publication of books, I don’t know that I ever would’ve written a single one. (Maybe a collection or two of essays, though, if I had found any publisher charitable enough to put them out.) It has been good for me to be pushed towards book-writing, but it’s not my natural métier — the essay is. And maybe the notebook is, even more.

But what about blog posts, like this one? This blog stands at the juncture of the essay and the notebook. Some of these posts are essays, though usually briefer than the ones that get published by other people; others are basically notebook entries shared with the public. What makes a post an essay is completeness: a story told to the end, a train of thought traced to a destination, a pattern of ideas or responses fully woven. Conversely, you can tell that a post is essentially a notebook entry when I say something like “I’ll revisit this idea later” or “Perhaps a topic for a future post.”

In my recent series of posts on the family I was writing on a topic so complex, so nuanced, so difficult that it would have been an impertinence, I think, to issue a finished word. I would dishonor the multiplicity of people’s experiences, the complexity of my own experience, by offering anything like a complete statement. So I put some thoughts out there, related them to one another as best I could, and now I am pausing to reflect. Probably there will be more later. On a blog there can always be more later, and one of the best uses of hyperlinks is to link to your earlier self, even (or especially) when you think your earlier self was wrong about something or left something out.

It’s great to finish (or in my case abandon) something: to tell this story, to make this argument as well as you possibly can, crafting it with all your skill, and sending it out into the world to make its way as best it can. But there’s a place also — and I feel this increasingly strongly as I get older — for the tentative and incomplete, for “I’ll revisit this later,” for “Oh, I forgot this when I wrote that” — for, maybe above all, being corrected by charitable but honest readers and then being able to try again on the basis of what the lawyers call “information and belief.” I am always, and hope I always will be, gathering more information and developing my beliefs. As the man also said, “Old men ought to be explorers.”