From my book Original Sin: A Cultural History:

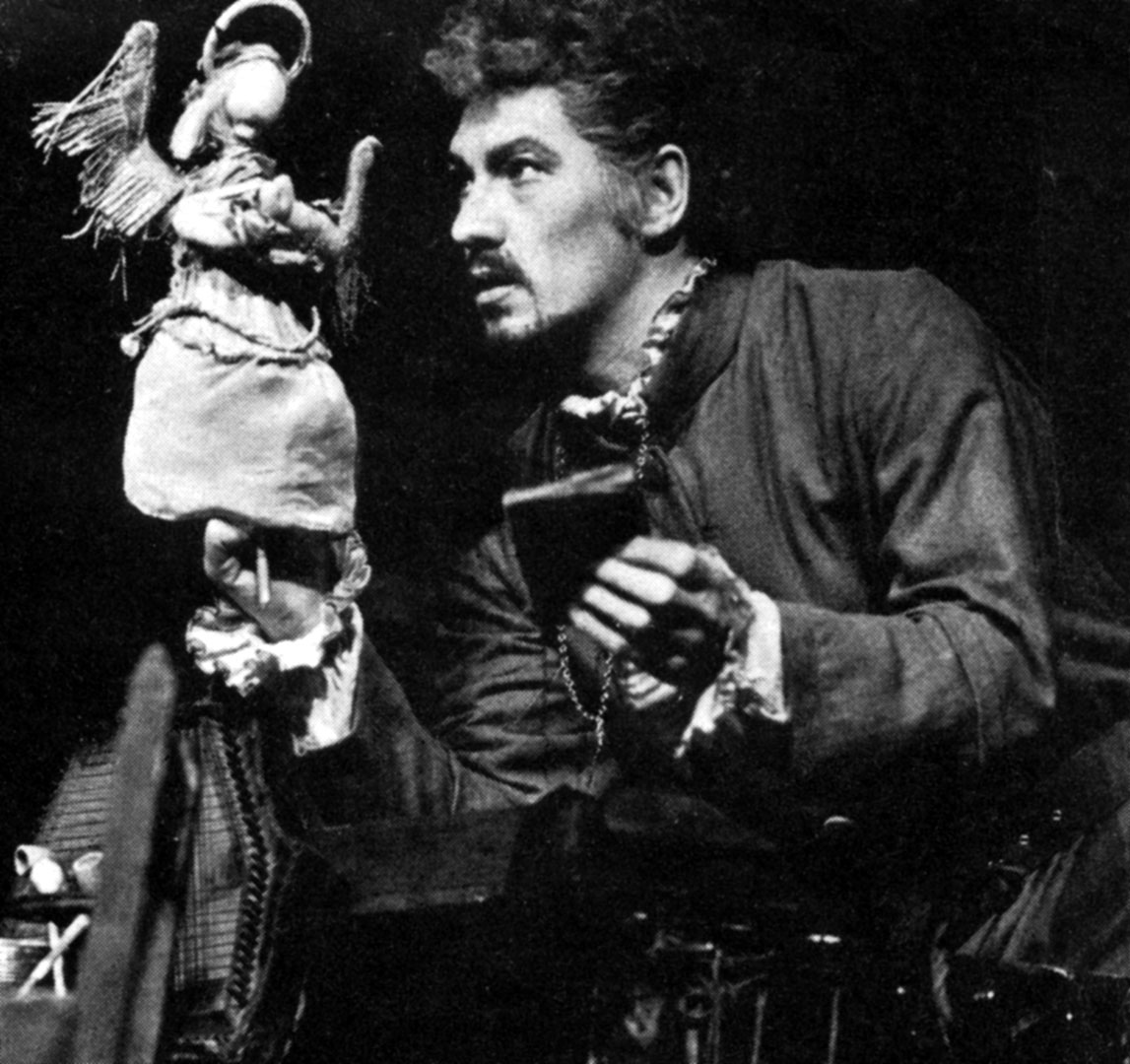

In 1974, the famous theatrical director John Barton staged [Christopher Marlowe’s] Doctor Faustus for the Royal Shakespeare Company and chose for the leading role an unknown young actor by the name of Ian McKellan. Shrewd move, that; but he made other decisions that are equally interesting and important, though from a different point of view. The directorial problem with which Barton was faced is simple yet serious: how … could we [moderns] possibly take seriously the appearance of the Good and Evil angels? And his solution was a brilliant one: he made them into hand puppets, held by Faustus himself, their lines spoken by him.

A brilliant solution on more than one count: not only does he avoid sniggers from the audience at the appearance of the debating spirits, but he simultaneously enables an understanding of Faustus that is perfectly commensurate with twentieth-century psychology. For if it was the genius of Prudentius and his followers to reach into the divided self and pull out its voices, giving them bodily substance and individual identity, it was the genius of Freud and his followers to stuff them all back into the box. When Freud sees the Good Angels and Evil Angels of our stories as projected externalizations of our own inner conflicts — puppets made by us and able to speak only through our acts of ventriloquism — he is simply returning us to the world of Augustine, in which “the devil made me do it” is scarcely a legitimate excuse. Do we sin because we heed the devilish voice in our ears? Or do we heed that voice because we have already sinned? Whatever answer we might give has little practical significance. The divided self is our inheritance no matter what, and in the pain and disorientation of that experience we may not even care whether we were torn from the inside out or the outside in.