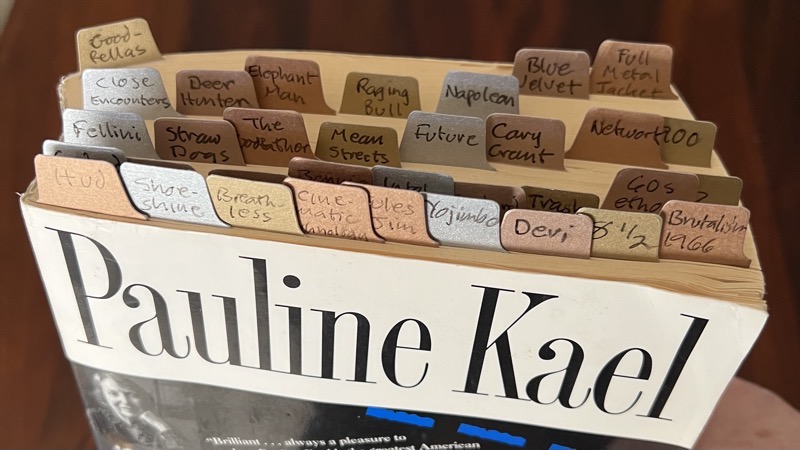

That’s my copy of Pauline Kael’s For Keeps, the enormous collection of the essays on and reviews of movies that she most wanted to preserve. It’s pretty marked up, because Kael, more than any other film critic, helps me to understand what I think about movies. Re: my three categories of thinker, Kael is neither a good Explainer nor a reliable Illuminator — nothing in Renata Adler’s notorious takedown of Kael is wrong, exactly, even if it relies far too heavily on strategic omission — but she’s one hell of a Provoker.

You’ll notice how much how many more markers there are in the early pages then there are in the later ones. This has something to do with my own interests, but I think it has a lot more to do with how Kael’s relationship to the movies changed over the decades. This first occurred to me as I was reading her review of Blade Runner, which is a largely hostile one … but the hostility really wasn’t, for me, the problem (especially since that initial theatrical release of the movie was indeed badly flawed). Rather, while reading I just felt that Pauline Kael was not made to be reviewing movies like Blade Runner, that by this point the movies had a traveled down a path that was simply alien to her sensibility.

She was still capable of having intense responses to movies, positive ones as well as negative. For instance, there’s a scene in My Left Foot that — in one of her last reviews — she says might be the most emotionally wrenching she had ever seen in movies. (Any of you who have seen My Left Foot will know precisely the scene that she’s talking about.) So it’s not as though she had come to hate new movies; she thought that some were good and most were not so good, and that was no different in the Eighties than it had been in earlier decades. But it is pretty obvious that her intellectual and aesthetic formation is not really suited to the direction that movies take from the Eighties onward.

She retired in 1991, largely because of the onset of Parkinson’s disease, which some people think may have affected her mind. I don’t know about that, but certainly many of the reviews that she wrote in the Eighties were indistinguishable from the work of other critics. That was never true of her earlier work, which was sometimes right and sometimes wrong, sometimes exhilarating and sometimes exasperating, but it was all very obviously written by Pauline Kael and could not have been written by anyone else.

I think maybe she might’ve retired a decade too late; but she certainly should have gotten started a decade earlier. She only began publishing regularly in her forties, and didn’t commence her regular column for the New Yorker until she was fifty. If her talents had been recognized earlier she could have taken over for James Agee, who was only a decade older than her, as the most important American writer about film. It would’ve been wonderful to get Kael’s real-time takes on the films that emerged from the late Forties to the late Fifties.

In 1969 Kael wrote a long essay for Harper’s called “Trash, Art, and the Movies” that I’m going to return to in another post — it helps me think about what I was talking about in yesterday’s post — but I’ll leave you with a passage from it that’s classic Kael, and that shows you what we’ve been missing in writing about movies since she left the scene:

A good movie can take you out of your dull funk and the hopelessness that so often goes with slipping into a theatre; a good movie can make you feel alive again, in contact, not just lost in another city. Good movies make you care, make you believe in possibilities again. If somewhere in the Hollywood-entertainment world someone has managed to break through with something that speaks to you, then it isn’t all corruption. The movie doesn’t have to be great; it can be stupid and empty and you can still have the joy of a good performance, or the joy in just a good line. An actor’s scowl, a small subversive gesture, a dirty remark that someone tosses off with a mock-innocent face, and the world makes a little bit of sense. Sitting there alone or painfully alone because those with you do not react as you do, you know there must be others perhaps in this very theatre or in this city, surely in other theatres in other cities, now, in the past or future, who react as you do. And because movies are the most total and encompassing art form we have, these reactions can seem the most personal and, maybe the most important, imaginable. The romance of movies is not just in those stories and those people on the screen but in the adolescent dream of meeting others who feel as you do about what you’ve seen. You do meet them, of course, and you know each other at once because you talk less about good movies than about what you love in bad movies.