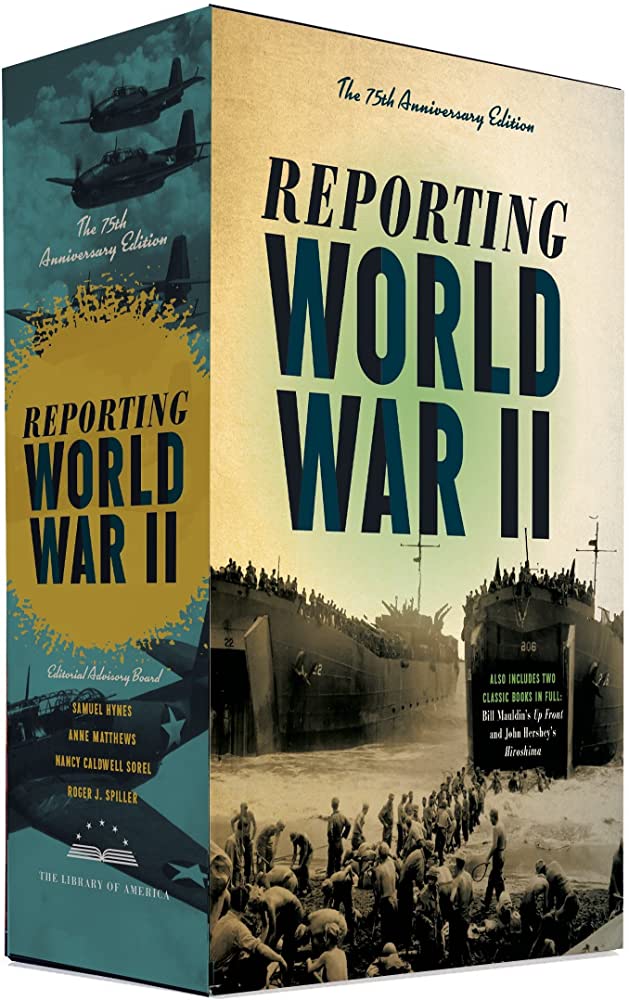

This is the two-volume Library of America anthology of World War II journalism — reports sent back from the field, or written on the home front, tracking the war week by week — and these books have given me one of the most powerful reading experiences of my life. It has taken me a long time to get through them; sometimes after only twenty or thirty pages I had to set the book aside for a while, for a few days or a week, and return to it when my nerves had settled.

That war is arguably (I want to say “surely”) the worst thing to have happened to humanity — any true account of it features horror after horror after horror; so much so that after a while you wonder whether you should be reading about it at all. Something James Agee wrote about watching documentary footage of the war — originally published in The Nation in March of 1945 and included in the second of these volumes — is compelling about its specific topic, but also about even reading these accounts of the nightmare:

I am beginning to believe that, for all that may be said in favor of our seeing these terrible records of war, we have no business seeing this sort of experience except through our presence and participation…. Perhaps I can briefly suggest what I mean by this rough parallel: whatever other effects it may or may not have, pornography is invariably degrading to anyone who looks at or reads it. If at an incurable distance from participation, hopelessly incapable of reactions adequate to the event, we watch men killing each other, we may be quite as profoundly degrading ourselves and, in the process, betraying and separating ourselves the farther from those we are trying to identify ourselves with; none the less because we tell ourselves sincerely that we sit in comfort and watch carnage in order to nurture our patriotism, our conscience, our understanding, and our sympathies.

A necessary point powerfully put. Yet on balance I do think the war is worth reading about, if for no reason than to cure the reader of the sheer frivolity endemic to our current political discourse, especially the discourse of our politicians. Our political world is a room in which there are no grownups, and if it does nothing else reading these accounts will bring that fact quite forcibly home to you. But it also reminds us of — here I want to avoid the all-too-common phrase “what human beings are capable of,” because the real point to be noted is not what we can do but what so often we gleefully or determinedly do. What we seem hard-wired to do, and to do more effectually as the power of the nation-state (supported by its corporate allies) increases. But that’s a topic for another day.

Some writers appear frequently here, and two stand out most vividly in my mind. The first is A. J. Liebling — after reading a few of his pieces I was so taken by their brilliance that I stopped reading them and bought the LoA volume devoted to his war writing. I’ll read that one straight through when I can. The other is Martha Gellhorn, who spent much of the war writing for Collier’s.

I’ll end here by quoting one passage in particular, in part because it reminds me that even in the midst of the horror there were dignity and grace and … something still more. In the immediate aftermath of D-Day Gellhorn, having been denied a press pass, disguised herself as a nurse and slipped onto the first hospital ship sent to gather and treat the wounded from the beaches of Normandy. Having been loaded with injured soldiers, Allied and German alike, the ship moved back into open water, headed for England. As the doctors (four of them), nurses (six), and orderlies (fourteen) worked desperately and nonstop to treat hundreds of men, German fighters swarmed overhead trying to kill them all. Gellhorn:

The American medical personnel, most of whom had never been in an air raid, tranquilly continued their work, asked no questions, showed no sign even of interest in this uproar, and handed out confidence as if it were a solid thing like bread. If I seem to insist too much in my admiration for these people, understand that one cannot insist too much. There is a kind of devotion, coupled with competence, which is almost too admirable to talk about; and they had all of it that can be had.