Skyscraper (1959) is a 20-minute documentary film — mainly in black-and-white, though color enters in an interesting way near the end — about the construction of a building in Manhattan called the Tishman Building, then carrying the address 666 Fifth Avenue. The number was recently changed to 660, which it could have been all along, since the building occupies several lots, including both 660 and 666. Perhaps its current owner, one of Jared Kushner’s companies, thought the association of a Trump family member with the Mark of the Beast was subject to unfortunate interpretation. But when it was completed in 1957 the three big sixes were quite prominently displayed on the façade.

You can see the film here, though that’s a bad print — if you happen to subscribe to the Criterion Channel you can see a much better version. It’s fascinating in a number of ways.

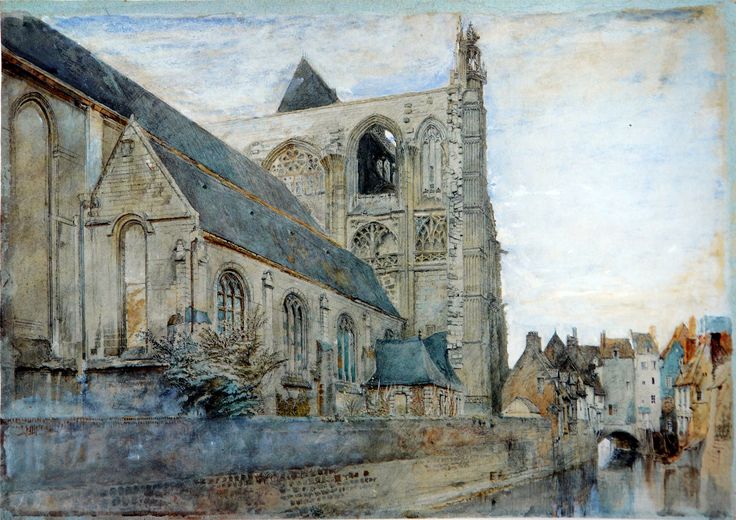

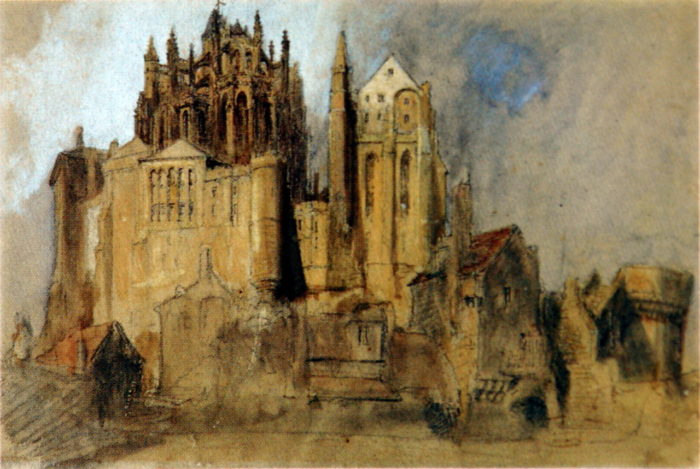

Some of the filming takes place high above the streets, and certain shots look down on St. Patrick’s Cathedral. The narrator comments that St. Paddy’s had seen three buildings go up at 666, but the real story is more complicated. The first buildings on that stretch of Fifth Avenue were a series of mansions — one of which was designed by the famous architect and infamous human being Stanford White — built for the Vanderbilt family.

This one came earlier and was designed by Richard Morris Hunt:

They called it Le Petit Château, isn’t that cute. A château with no green thing in sight is no château at all, in my book.

Gradually these were torn down; by the time the Tishman Building started construction, the area had been reduced, as far as I can tell, to a 12-story office building and a parking lot. (The various histories are a little vague on these points.)

In any case, in 1957 construction was preceded by demolition, and when the dump trucks carried away load after load of rubble they took it to New Jersey, where it was used to reclaim marshland. So there are who knows how many buildings in New Jersey built on ex-Manhattan rocks.

When the building opened, among its most notable features was its lobby, which featured two artworks by the great Japanese-American sculptor Isamu Noguchi, a flowing ceiling and a differently flowing waterfall-wall.

These were removed in 2020. Thanks a lot, Jared.

For a while, plans were ongoing to demolish the 41-story building — stripping it down to its steel frame and then rebuilding it twice as high, to a design by Zaha Hadid. These proved too ambitious. But surely it won’t be long before St. Patrick’s Cathedral watches yet another building on those lots come down and yet another rise up.

Anyway: the documentary is cool, you should watch it.