The inchoate and incomplete “theology of the city” that I wrote about last week has always, is my mind, been connected to London as strongly as to Jerusalem and Babylon and Rome. Here’s a new entry in my longstanding if intermittent series about the great city on the Thames.

He is known to us by another name, and linked in our minds with the city in which he was murdered, but throughout much of his adult life he would have been known as Thomas of London. Thomas, because he was born, probably in the year 1118, on the the feast-day of St. Thomas the Apostle, December 21; and London because he was born in that city, on the street called Cheapside. His father had come to England from Rouen, in the aftermath of the Norman Conquest; his mother was from Caen. Later stories that Thomas was Anglo-Saxon are wholly untrue. He was, as his shrewdest biographer says, “perhaps the first of England’s great men to be essentially and professedly a Londoner.”

“Cheapside” is derived from Old English words meaning “marketplace,” and we know what people would have brought to sell at the market by the nearby street names: Bread Street, Milk Street, Poultry, Honey Lane. When Thomas was born the place was more of an open area in the growing town than what anyone today would call a street, but it was a major thoroughfare, and when the Kings of England made royal progress from the Tower of London at the eastern end of the city to the Palace of Westminster, arcing along the great bend in the River Thames, they always passed along Cheapside.

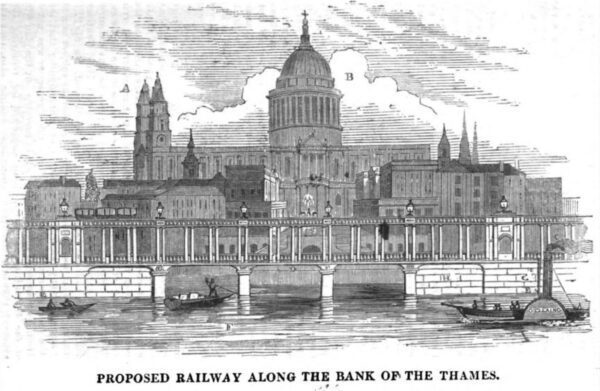

Just to the west of his birthplace Thomas would have seen, rising above the rest of the town, London’s greatest work in progress: St. Paul’s Cathedral. Construction had begun in 1087, after a great fire destroyed its predecessor and indeed much of the city — a story that would be repeated in 1666, leading to the building of yet another St. Paul’s, the great domed one that we know today. Scholars believe that the church Thomas saw going up, which is usually called Old St. Paul’s, was already the fourth church to be built on that site, which makes one wonder why the people of London didn’t give up and try elsewhere. But the site was both an intrinsically good one — situated on a small hill overlooking the Thames — and one hallowed by sanctity, for St. Erkenwald, a Bishop of London who died in 693, was buried there, and many pilgrims visited his grave to seek his intercession.

Later in life, when Thomas had become a great man, indeed the greatest churchman in England, he had learned clerks who worked for him, and one of them — William Fitzstephen, who was present at his murder — wrote a biography of Thomas that he prefaced with an account of the city in which Thomas was born. London was William’s native city too, and he took great pride in it and believed that its character explains a good deal about Thomas. London was the place of Thomas’s “rising,” as Canterbury was of his “setting.” William’s Descriptio Nobilissimi Civitatis Londoniae — Description of the Most Noble City of London — ranges widely over the customs and practices of the city: for instance, we learn of a magnificent riverside restaurant that not only created lavish feasts but prepared takeaway meals for customers in a hurry. We learn also about commerce, sports and games, green meadows, wells of sweet water, and places of learning.

But William also wishes that we should know how pious a city London was, how “blessed in Christ’s religion.” Though we now believe that no more than 20,000 people lived there, William says that the city boasted thirteen major churches and 126 smaller ones. The major ones were monastic foundations of one kind or another, the smaller ones parish churches. It was this atmosphere of piety, William believes, that nourished the boy who would one day become St. Thomas Becket, St. Thomas of Canterbury. By the time Thomas was ten years old, William says, the boy already radiated holiness. At that age Thomas was sent for his schooling across the river to Merton Priory — situated in what is now a part of the metropolis but then was in the countryside, well beyond what William would have thought of as the boundaries of London — and when Thomas’s father Gilbert came to visit him there he found the prior, Robert, prostrating himself before the boy. When Gilbert expressed horror at this reversal of proper roles, the prior replied, “I know what I am doing. This boy will be a great man before the Lord.”

A likely story, one might be pardoned for thinking. And even at that time there were many in England who doubted that London could such an incubator of holiness. Richard of Devizes, a monk from Winchester and a contemporary of William’s, wrote bluntly: “If you do not wish to dwell with evildoers, do not live in London.” For him, and for many outside the capital, the city was already known as a place of all kinds of sin, but especially of naked avarice. And if one revisits William’s Descriptio with this in mind, one might notice that he spends more time describing the commerce and sports and games than the churches. He is never anything less than admiring of the worldly greatness of his native city. It was that particular greatness to which Thomas of London was a natural heir; but in the end he chose a different inheritance.

•

When Thomas was a very small boy, another Londoner had a vision. We do not know much with certainty about this man, not even his name. He is usually called Rahere or Raherius. He was clearly associated in some way with the court of King Henry I: in the fragmentary and confused records that have come down to us, he is sometimes referred to merely as a courtier, sometimes as Henry’s herald, though most often as the King’s jester. But in a document from 1115 his name is listed as one of the canons of (that is, priests attached to) St. Paul’s Cathedral. The taking of holy orders is not necessarily incompatible with playing the fool in a king’s court, especially in a period when kings had wide latitude to make gifts to their favorites; but the stories about Rahere do make for a curious amalgamation.

In any event, Rahere’s story now takes a turn: When he was on pilgrimage to Rome he fell ill, and when he was near death St. Bartholomew appeared before him and pledged to spare his life, but only on the condition that Rahere return to London and build a hospital. (In some versions of the story, Rahere in his vision is attacked by a terrifying monster, which the saint drives away.) Upon his return Rahere got busy. With royal and episcopal approval, he acquired a site next to the great livestock market of Smithfield, about half a mile north-west of Cheapside, and began, in 1123, to build both a church and a hospital, both named for the saint who has rescued him from death. He became the prior of the church, a position he held until his death in 1144; and there he is buried.

Thanks to the Great Fire of London in 1665 and the general depredations of time, nothing remains of the Cheapside of Thomas Becket, but some of what Rahere built remains to be seen. The site stands just at the northwestern edge of the City of London, which is why the Fire, which started in Pudding Lane in the eastern part of the city and near the river, never reached it; and when Henry VIII chose to re-found the hospital after he had dissolved England’s monasteries, it became formally known as the “House of the Poore in West Smithfield in the suburbs of the City of London of Henry VIII’s Foundation.” The original hospital and its several chapels are long gone — though a late-medieval replacement for one those chapels remains as the church of St. Bartholomew the Less — so the chief embodiment of Rahere’s great project is the church known as St. Bartholomew the Great, or, more familiarly, Great St. Bart’s.

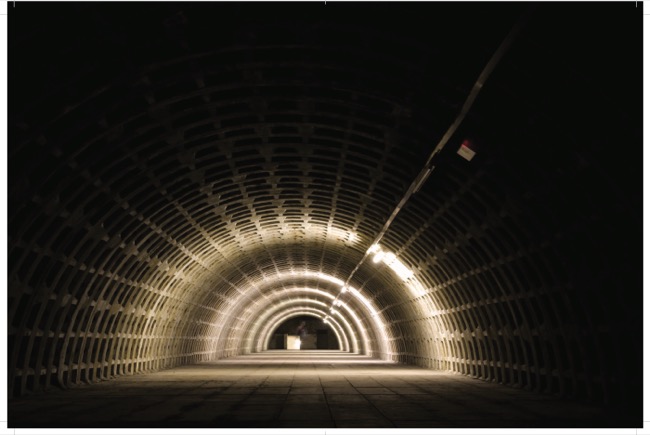

The visitor, or worshipper, today enters the church by passing along a walkway that is almost a tunnel — an urban version of a holloway, an old path sunk below the surrounding ground and overgrown by vegetation. For the city has been built up, level by level, in the nine hundred years since Rahere’s workmen laid the foundation for the church, and the surrounding streets run six fit or more above the entrance. Opening the doors, you find yourself in a tiny area, a dark wooden partition blocking any view. But you may well smell incense. And then you walk through one of the little interior doors and and ancient walls rise up around you, the heavy thick Norman stonework, the rounded arches, the windows that seem small if you have been in Gothic or new-Gothic churches recently. Around you is great mass, and a sense of the numinous, as though prayers that have risen up from this place for nearly a millennium have lest behind some invisible, yet palpable, residue.

I have visited Great St. Bart’s many times, but when I think of it I always recall the time I attended Evensong when a visiting Russian choir sang music from Rachmaninoff’s Vespers. The somber and gorgeous music, which though composed in the twentieth century is shaped by ancient forms and tones of Russian music and prayer, seemed uncannily congruent with the dim and forbidding beauty of the old church. I was almost surprised when I looked around me to see people in modern clothing rather than robed and cowled monks.

Meanwhile, just a few feet away, the work of Barts (as the hospital is now generally called) went on, its multifarious electrical machinery humming, its practitioners generally oblivious not only to the worship going on in the church but to the curious and wonderful fact that that worship and their own labors on behalf of the sick arose from a single impulse, a single obedience, on the part of a man who once had found himself far from home and close to death and helpless in the face of his own suffering. The call of those who served in that hospital at its founding was “to wait upon the sick with diligence and care in all gentleness,” as the call of the monks was to pray for all who suffered in this life, and in the next too, if their place in the next life was Purgatory.

And we should remember too the goings-on a few feet on the other side of the church from Barts, in the great Victorian edifice of Smithfield Market, where the lorries come and go all day and most of the night, where the gods of commerce receive their proper worship as they did when William FitzStephen looked upon his city with such admiration. But this was also once a place of execution too; and also nearby was the site of Bartholomew Fair, that “school of vice which has initiated more youth into the habits of villainy than Newgate itself” (so the Newgate Calendar said). All the world’s wisdom and folly in a few square yards, with an ancient and beautiful church in the middle of it.

This is amazing.

This is amazing.