The central and absolutely essential premise of Ross Douthat’s new book Believe, the point from which the whole argument begins, is this: There is a genus of human belief and practice called “religion,” of which Christianity is one of the species. My problem with regard to Ross’s book is that I have come quite seriously to doubt this premise. My larger problem is that I don’t know quite how to do without this premise, since it is so deeply embedded in almost all discourse on … well, I guess I have to say on religion.

My difficulty was brought home to me when I was writing the Preface to my forthcoming book on Paradise Lost. That book is one of a series called Lives of the Great Religious Books, which meant that in said Preface I needed to explain and justify my claim that Milton’s poem really is a religious book — which, I argue, it is in some ways, though not in others: its relationship to Christianity is radically different than that of, say, the Book of Common Prayer, the subject of my previous book in the PUP series. In order to do this, I had to take the concept of “religion” seriously. Or semi-seriously.

I began thus:

Many years ago I heard it said — I wish I could remember by whom — that the only thing the world’s religions have in common is that they all use candles. Thus Sir James Frazer, in beginning his great The Golden Bough, wrote that “There is probably no subject in the world about which opinions differ so much as the nature of religion, and to frame a definition of it which would satisfy every one must obviously be impossible. All that a writer can do is, first, to say clearly what he means by religion, and afterwards to employ the word consistently in that sense throughout his work.”

But I had to settle on some kind of definition, so here’s the relevant footnote:

Emile Durkheim’s definition is a useful one: “A religion is a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, that is to say, things set apart and surrounded by prohibitions — beliefs and practices that unite its adherents in single moral community called a church”: Emile Durkheim, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life, trans. Carol Cosman (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001 [1912]), p. 46; italics in original. Durkheim is using the term church in a very broad sense, though one may doubt whether it can possibly be broad enough to cover all relevant cases. This definition contains both functional and dogmatic elements, but as Durkheim unfolds his conceptual frame the functional strongly dominates.

After that I went on to argue that Paradise Lost is religious in a dogmatic but not a functional sense. I think my argument is correct, given the premises — but, as I say, the premises are what I’ve come to question.

Basically, I’ve come to believe the various things we call “religions” … well, here’s what I wrote in a recent essay:

I often tell my students that whether Christianity is true or not, it is the most unnatural religion in the world. Even a cursory study of the world’s religions will show how obsessed humans are with finding some way to (a) gain the favor of the gods, or transhuman powers of any kind, and/or (b) avert their wrath. Religious seeking is almost always about these two universal desires: to get help and to avert trouble. But in Christianity it is God who comes to seek and save the lost (Lk 19:10); it is God who reckons with His own wrath, himself making propitiation for our sins, and not for ours only but also for the sins of the whole world (1 Jn 2:2). The standard — or rather the obsessive — practices of homo religiosus have no place here. In Jesus Christ, the Christian gospel says, God has done it all.

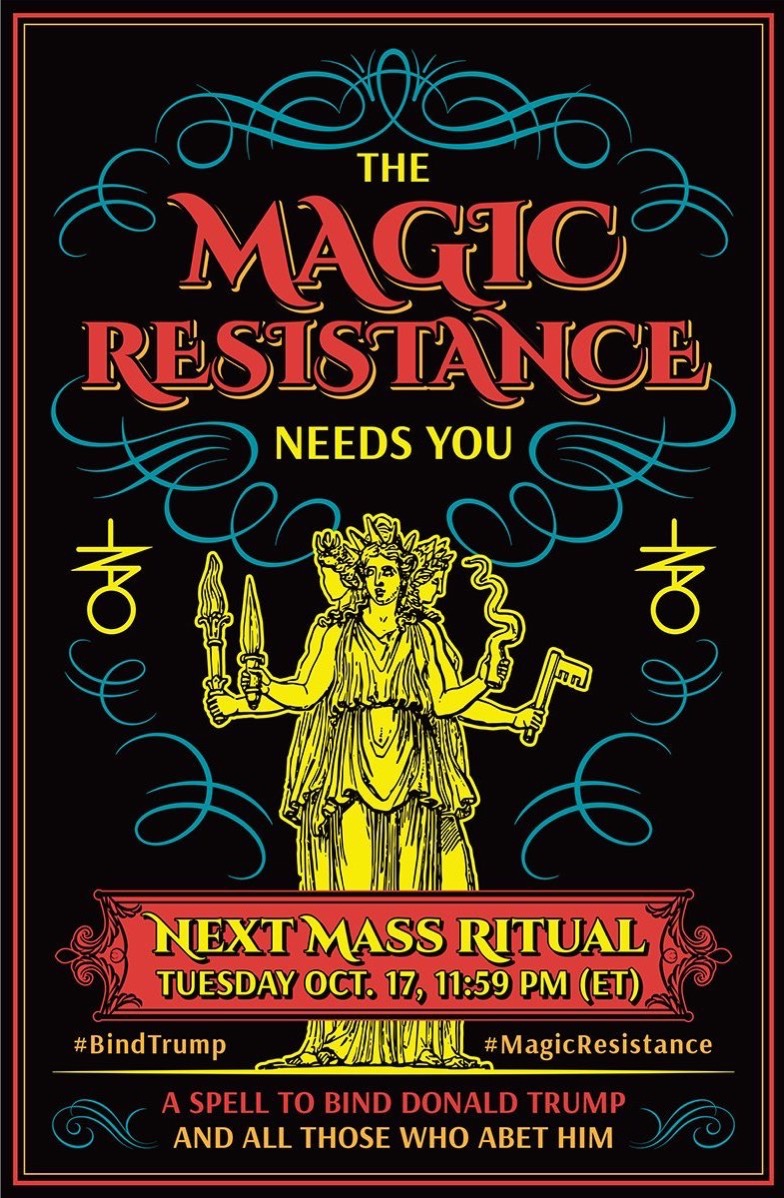

I say: This may be true or it may be false, but it is the Christian account of things, and it is very, very weird — so weird that it is easy, indeed natural, for us to fall back on the standard model of religion and turn our prayers into spells. How often do we think, perhaps in some unacknowledged place deep inside our minds and hearts, that when we come to church and say the appointed words and perform the correct actions, we are somehow getting Management to take our side?

The distinction between spells and prayers is Roger Scruton’s — read the post for the context — and it’s a useful one. I think it is the natural human tendency, the natural religious tendency if you must, to look for spells that can influence or even control the Powers That Be. But what use is a spell if the Name above all names — Jesus Christ — has already redeemed the world?

(I am speaking here of the greatest thing a religion might be expected to do. We also ask smaller things, and in those cases we often fall back on the old spell-habit, not realizing how secondary even the things that most concern us really are in the divine economy. Our inability to keep these matters in their proper perspective is a great theme in the letters of the apostle Paul, but that’s a subject for another time.)

Back to Ross’s book, near the end of which he writes this:

Some people’s encounters with religion in childhood aren’t negative or abusive so much as they are just sterile and empty, making the faith of their ancestors feel like a dead letter when it comes time to start on their own journey. That was how it was for the British novelist Paul Kingsnorth. He was raised to experience his isle’s Christianity as a hopeless antiquarianism, a thing that mattered only as a foil for modernity. His own adult spiritual progress grew naturally out of his environmentalism, which led him first into a kind of “pick’n’mix spirituality,” and then into a commitment to Zen Buddhism, which lasted years but felt insufficient, lacking (he felt) a mode of true worship.

He found that worship in actual paganism, a nature-worship that made sense as an expression of his love of the natural world, and he went so far as to become a priest of Wicca, a practitioner of what he took to be white magic. At which point, and only at that point, he began to feel impelled toward Christianity — by coincidence and dreams, by ideas and arguments, and by the kind of stark mystical experiences discussed in an earlier chapter of this book.

In Ross’s account, I think I’m right to say, this is a gradual convergence on the True Religion, and while I do believe that the Christianity Kingsnorth now professes (and professes shrewdly and eloquently) is indeed true, I don’t believe that when he was a Wiccan — saying actual spells! — he was close to that truth than when he was a Buddhist or “spiritual but not religious.” In fact, Buddhism has a better understanding of the uselessness of spells than Wicca. Buddhism, though the very concept of “god” is not intrinsic to it, in its frank acknowledgment of a cosmos wholly beyond our control might be closer to the Christian understanding of the world than any practice committed to the efficacy of spells.

I dunno. I’m still thinking this through. But right now my thoughts are running along these lines:

While I doubt the genus/species premise of Ross’s book, almost everyone else in the world accepts its validity. A point that in intellectual humility I should bear in mind. And because the whole world accepts its validity, maybe Ross is right to structure his book in this way.

But I am not at all convinced that a move from, say, atheism to Wicca is necessarily “a step in the right direction” — i.e., once you’ve entered the genus-town of “religion,” you’re closer to the species-house of Christianity than you were before. Indeed, I wonder whether many people might be less interested in Christianity as a result of such a move, since they might plausibly think that as long as they’re operating within the genus, does it really matter what species they prefer? (The “We all get to God in our own way” line has had a very long run and doesn’t show any signs of slowing down.)

It’s common to call people who move from one religion to another “searchers,” and usually Christians think of that as a good thing. But I doubt that many of the people we call searchers are really searching. We Christians don’t seek, we are found by the One who seeks us. And that may be more of a frightening than a consoling thought. I believe that C. S. Lewis, as God approached him, was feeling the right feelings:

I was to be allowed to play at philosophy no longer. It might, as I say, still be true that my “Spirit” differed in some way from “the God of popular religion.” My Adversary waived the point. It sank into utter unimportance. He would not argue about it. He only said, “I am the Lord”; “I am that I am”; “I am.”

People who are naturally religious find difficulty in understanding the horror of such a revelation. Amiable agnostics will talk cheerfully about “man’s search for God.” To me, as I then was, they might as well have talked about the mouse’s search for the cat.

Finally: Near the end of his book Douthat calls Christianity “the strangest story in the world,” a claim I enthusiastically endorse. But I think that if we take that claim with the seriousness it deserves, we might have to abandon the idea that Christianity is one of the things we call “religion.” Religion — if we must use the word — is a human activity that can be described more-or-less as Durkheim describes it. Christianity is something else altogether, I can’t help thinking. “For God so loved the world, that he gave his only Son, that whoever believes in him should not perish but have eternal life” is not only stranger than we imagine; it’s stranger than we can imagine.

It occurs to me, belatedly, that some of my earlier posts on enchantment are relevant to the argument I’m making here:— e.g. this one. But I’m wondering whether I’m moving the goalposts somewhat: perhaps I am criticizing Ross for something I’ve done myself. I’ll think about it and revisit the topic later.