In The Long Week-End, their entertaining, sardonic, and often insightful social history of England between the two world wars, Robert Graves and Alan Hodge assert that in the years immediately following the Great War, “Detective-novel writing was not yet an industry; Sherlock Holmes stood alone.” (That comment, like this post, refers only to the British situation; the American situation was quite different.)

This is perhaps a bit of an exaggeration. Historians like Graves and Hodge tend to ignore the Sexton Blake stories, presumably on the grounds that they were mass-produced, by multiple authors who worked from simplistic templates, and were aimed primarily at younger audiences. But they were extraordinarily popular and it seems that almost everyone read at least some of them. (When Dorothy L. Sayers was ill at school — the Godolphin School in Salisbury — she wrote to her parents to ask them to send her some Sexton Blakes.) And then, on what one presumes G&H would have thought a higher level of literary ambition, there were the Father Brown stories — but Chesterton, having written a pile of them between 1910 and 1914, did not write another until 1923.

Meanwhile, the Sherlock Holmes wagon continued to roll, though with a pause (as many things paused) in the war years, during which Conan Doyle published only one Holmes story, “His Last Bow,” which was an exercise in patriotism and, moreover, a spy story rather than a tale of detection. But Conan Doyle would, with great reluctance and annoyance, resume Dr. Watson’s accounts of Holmes’s adventures in 1921.

Two other data points should be introduced here. First, the publication in 1913 of what would become one of the most influential novels of detection ever written, E. C. Bentley’s Trent’s Last Case. And second, the 1910 trial and conviction of Dr. Crippen, which renewed interest in what we now call True Crime.

If you look at these matters from the perspective of the year 1914, here’s what I think you see:

- the Sexton Blake stories rolling ever onward, but according to a fixed formula;

- the Holmes stories continuing but more slowly, and at a far lower standard than Conan Doyle had established in the 1880s and 1890s;

- an interesting experiment in a type of detective radically different than Holmes (Father Brown), which appeared to be complete;

- another interesting experiment, this one a playful questioning of the plot conventions of the tale of detection (Trent’s Last Case);

- a renewal of interest in True Crime.

So the future of tales of detection did not appear to be bright, and there was no reason to think that it would become a central genre of fiction.

Then the War came, and such topics were placed, not on the back burner but off the stove altogether. It was difficult, or embarrassing, or just plain shameful to think about a domestic murder or a crime of passion or a killing for money when the greatest slaughter in the history of humanity was ongoing. One could easily imagine that period marking the end of the detective story as a popular genre of fiction.

When the War ended, though, it became possible and indeed desirable to think about such matters again. It was presumably a kind of relief to be able, once more, to consider malice and death on a human scale — death as a tragedy and a misery but not an unimaginably vast horror. So Conan Doyle resumed his Holmes stories with “The Adventure of the Mazarin Stone” in 1921, and Chesterton his tales of Father Brown with (I think) “The Resurrection of Father Brown” in 1923. But even more to the point:

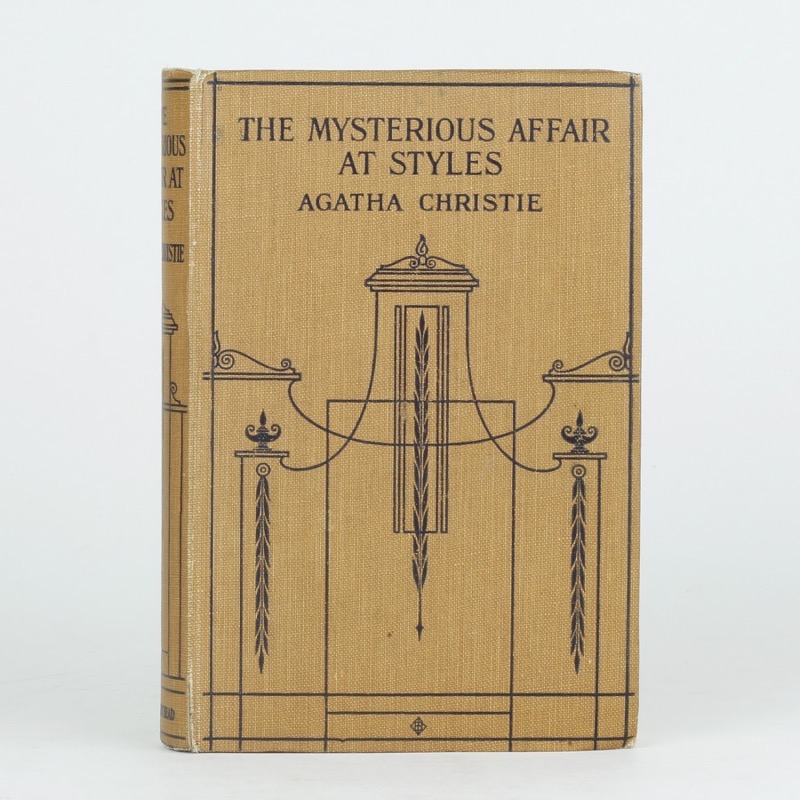

- Agatha Christie published her first mystery novel, The Mysterious Affair at Styles, in 1920;

- Freeman Wills Crofts published his first, and by far most influential, mystery novel, The Cask, also in 1920;

- Dorothy L. Sayers wrote her first detective novel, Whose Body?, in 1921, though it was not published until 1923;

- The Thompson-Bywaters trial was held in 1922, and after the execution of the convicted murderers in January of 1923, their story became a matter of extravagant public fascination for a very long time.

And so we were off to the races. The Golden Age of detective fiction — influenced at least as much by True Crime as by previous stories and novels — had begun. And I cannot help thinking that it was shaped, then and later, by the great shadow of Death hanging over Europe in the aftermath of the Great War.