The essay that I published earlier this year on “Resistance In the Arts” was largely inspired by my reading of one book, Ian MacDonald’s simultaneously maddening and magisterial Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. It’s important to to pay attention to that subtitle. McDonald wants to argue that the music that the Beatles made exemplifies the cultural movement that we call “the Sixties” better than anything else does, and he makes a very good case for that idea, in which I’m quite interested. But I’m even more interested in the final words of the actual narrative of the book, words written by way of introduction to a chronology of the 1960s. (That chronology, which serves as an appendix to the book, consists of four columns: what the Beatles were doing; what else was happening in pop music in the UK; key political and social events; and developments in the arts more generally — for instance, cinema, jazz, classical music, poetry, etc.) Here’s what MacDonald says to conclude his narrative and introduce that chronology:

There is a great deal more to be said about the catastrophic decline of pop (and rock criticism) — but not here. All that matters is that, when examining the following Chronology of Sixties pop, readers are aware that they are looking at something on a higher scale of achievement than today’s — music which no contemporary artist can claim to match in feeling, variety, formal invention, and sheer out-of-the-blue inspiration. That the same can be said of other musical forms — most obviously classical and jazz — confirms that something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties. Arguably pop music, as measured by the singles charts, peaked in 1966, thereafter beginning a shallow decline in overall quality which was already steepening by 1970. While some may date this tail-off to a little later, only the soulless or tone-deaf will refuse to admit any decline at all. Those with ears to hear, let them hear.

So that’s MacDonald’s blunt assessment. And what launched my essay was a double response to that paragraph. On the one hand, I thought that in relation to pop music, he is 100% correct. But the sweeping judgment I have highlighted, about “the soul of Western culture,” is less readily defensible. He wrote those words in the mid or late 1990s. In retrospect, it seems to me that classical music was in a much, much better place in the 1990s than it had been in the 1960s; similarly, the architecture of the Nineties was significantly more varied and inventive than architecture in the Sixties, partly as a result of certain technical changes, including CAD (computer-assisted design). I could give other examples.

Thus MacDonald’s Grand Narrative about Western culture — his assumption that Western culture is one giant, uniform Thing that is always on a single trajectory, either ascending or descending — is just nonsense, if also an all-too-common form of nonsense.

But: at any given moment in history in any given location, certain specific arts may operate at a higher level than they do at other times, or in other places. So I began my essay by noting how much better English drama was in the period between 1590 and 1620 than it ever had been before or ever would be again — and that is true even if you factor Shakespeare out of the equation. (You still have Marlowe, Webster, Jonson, Beaumont & Fletcher, etc.) Ditto the outpouring of genius in pop music between, say, 1962 and 1975, an outpouring that’s astonishing even if you factor the Beatles out of the equation. And what such stories suggest, or anyway what they suggest to me, is that circumstances can conspire to make a particular art form more dynamic at some moments than it is at others.

I’m not sure that I made myself perfectly clear in that essay. I’m a bit frustrated with it. But I still think that the chief point that I was pursuing is an absolutely vital one. We need to think about what kinds of circumstances encourage outstanding art and what kinds militate against outstanding art. In the essay I argued that there must be a balance between forces that enable and forces that resist, and that that balance is at once technological, economic, and social. You have to be able to do and make certain things, but the making should not be too easy, just as you should not be totally blocked from achieving what you’re trying to achieve. I mentioned the Beatles song “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which creates special effects through the use of five tape loops, loops which are placed within the song in a cunningly designed sequence. The loops (made by Paul McCartney on a tape recorder he had at home) were not easy to create, which is why there were only five of them; but five turned out to be the perfect number, because that allowed both repetition and variation, both of which are key to successful art. Moreover, while the Beatles were free to add those tape loops to the song, they were not (yet) free to spend six months in the studio or to make 10-minute songs.

The Beatles were immensely talented, to be sure, and were surrounded by equally talented support in the producer George Martin and the engineer Geoff Emerick; but Taylor Swift is also extremely talented and knows how to surround herself with gifted producers, engineers, and musicians, and yet, for all her enormous popularity, she isn’t changing the face of music. Her musical language is basic and predictable: given any two consecutive chords of a Swift song, the listener can predict with a high degree of confidence what the next one will be. She has not, to my knowledge, written or performed a single song that alters even in the tiniest way the landscape of pop music, while, by contrast, there was a period of five years during which the Beatles were doing that every few weeks. Maybe those conditions simply can’t be recreated; maybe Taylor Swift, and indeed everyone working in the aftermath of the Beatles’ meteoric career, is, in Harold Bloom’s term, belated. But, on the other hand, maybe we’re too quick to accept belatedness.

One of the reasons we still listen to the Beatles (one of the reasons we still read or watch Shakespeare) is that for them, in their time and place, they discovered the ideal balance between enablement and resistance; the stars aligned for them. (When the Beatles broke up the stars went out of alignment, forever; even if John Lennon had lived and the band had reassembled, they wouldn’t have been able to come close to what they achieved in the Sixties. The balance of resistances had altered, and for the worse.) I tried — and, I think, failed — to figure out what specifically it looks like when the stars so align for artists, and then to go beyond that to ask a question: Is there anything that we can do to help those stars to align?

You know, when absolutely staggering greatness shows up, I don’t think we can pay too much attention to it. We should not just look at it and applaud it, but also try to ask ourselves, in the most serious and intense way possible, What enabled that, and how can we enable something else that’s equally great?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I keep thinking about a tossed-off comment in Ian MacDonald’s book. He’s writing about a song that John and Paul wrote together — I don’t remember which one, but it doesn’t matter — and in that song there’s a moment when the standard, the expected, harmonic progression calls for an A major chord — but the Beatles go to A minor instead. Many sophisticated musicologists, MacDonald says, have studied this moment and written with analytical rigor about the harmonic language the Beatles employ at this moment and the different ways one might conceptualize it. But that’s all wrong, MacDonald says.

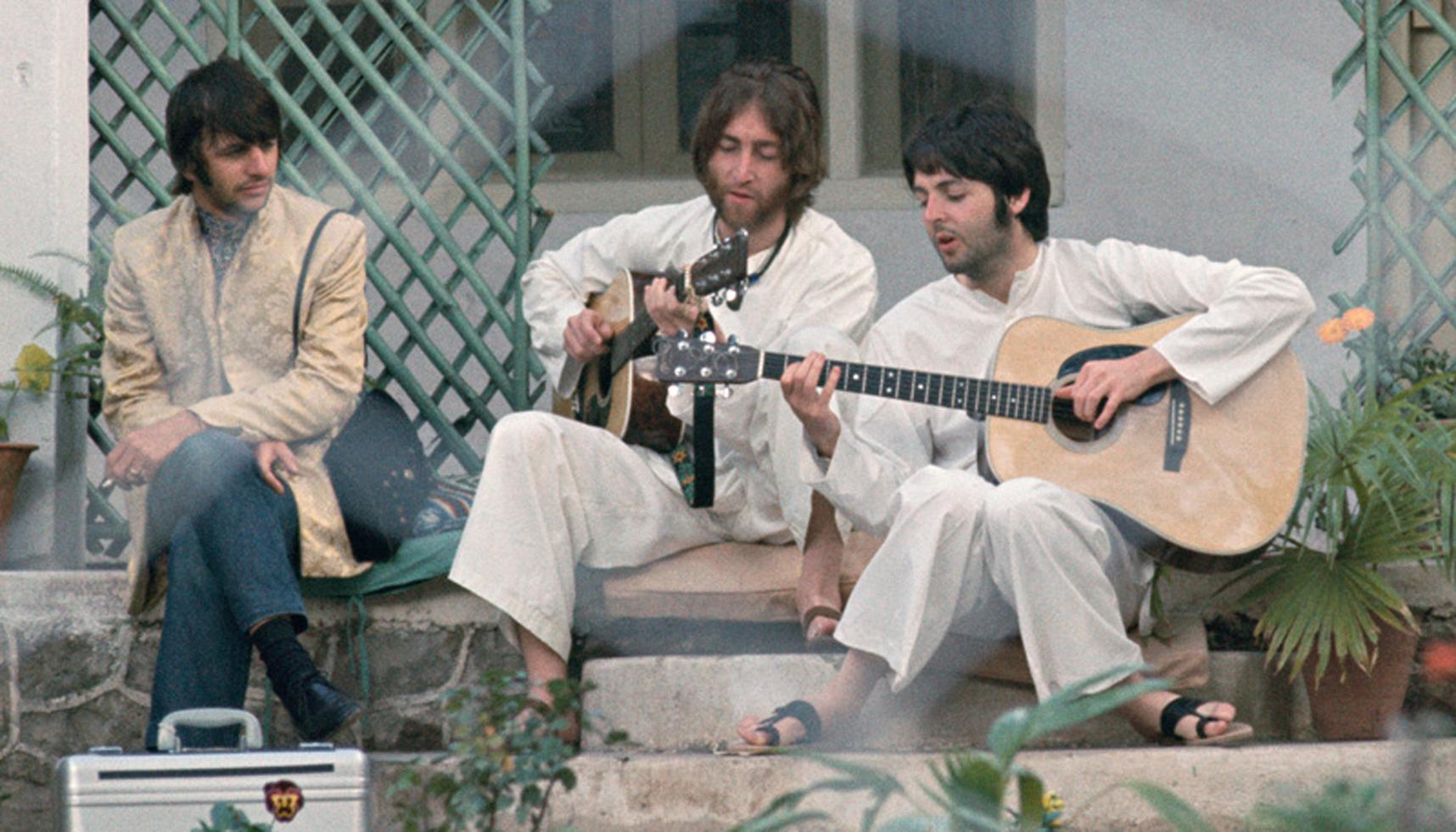

The key point is this: John and Paul were sitting in a room and each of them had a guitar on his lap. That’s the thing to remember, because every guitar player knows how much easier it is to play an A minor chord than an A major one — and, even more important, how much easier it is to riff on an A minor chord, to introduce hammer-ons and pull-offs that make the song sound better. (This is true when using standard tuning anyway — what I like to call Em7add11 tuning — which the Beatles almost always did.) Almost certainly, MacDonald says, at the moment when the A major chord would’ve been the most obvious thing in the world to play, either John or Paul went to the A minor instead — and lo and behold, it sounded cool. So they kept it.

Handmind at work.

You have to remember that neither of those guys could read music; neither of them wanted to read music. Nor did they have access to modern digital tools for music creation. What did they have? Four things:

- guitars

- ears

- hands

- musical memories

And those were the tools they needed.

And maybe that’s Step One. If we want to reinvigorate the arts, if we don’t want culture to come to a standstill, maybe we need to start with a radical minimalism. Artists: deprive yourselves of everything except the absolutely essential tools. You can’t stream, you can’t use a DAW, you can’t look anything up online, you don’t have an iPad. You have your sensorium and you have the most basic tools imaginable — a pencil, a lump of clay, a pennywhistle or a ukelele. Go.