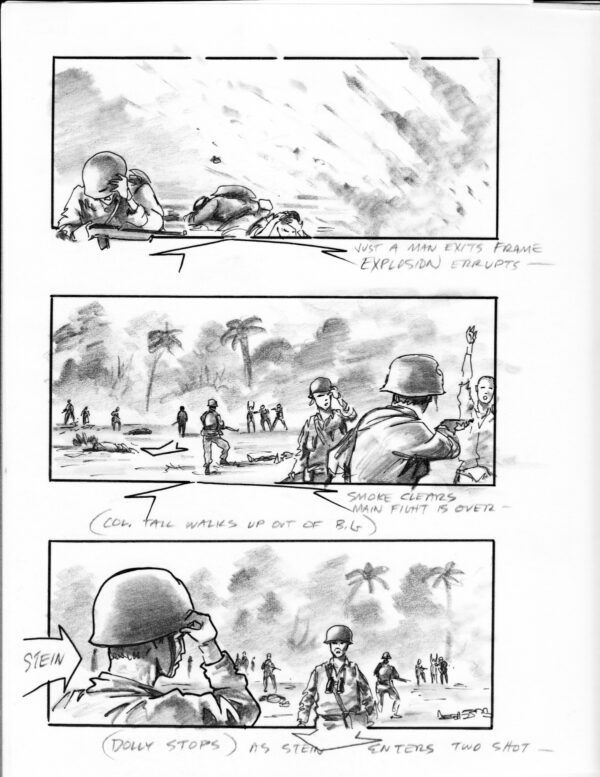

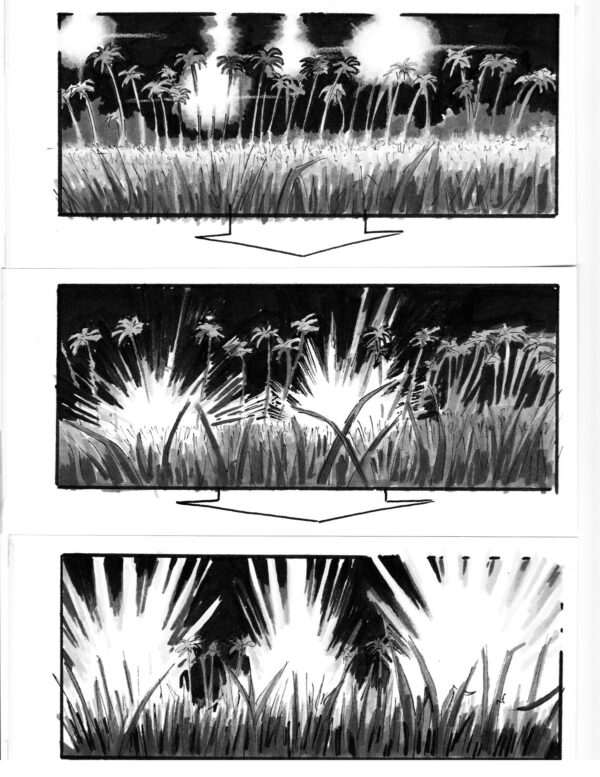

Mark Bristol’s storyboards for Terrence Malick’s The Thin Red Line.

Stagger onward rejoicing

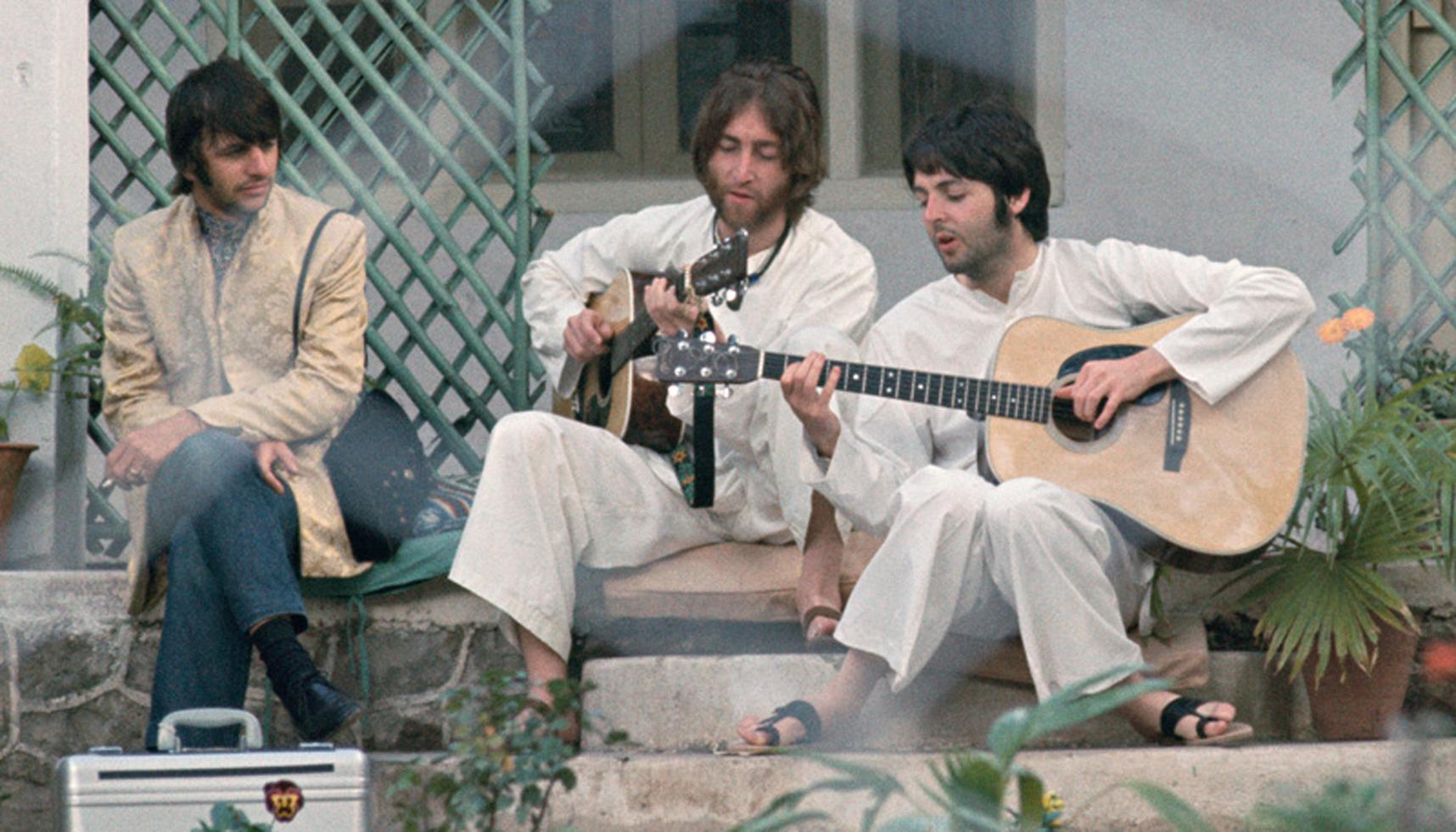

In 1969, when the Beatles were recording the album that became Abbey Road, Paul McCartney would come in every day to record a vocal track. (He lived near the studio, so it was easy for him to drop by.) The vocal he was trying to get right was “Oh! Darling” — a song that, some years later, John Lennon would say was better suited to his voice than Paul’s — and each day Paul would perform one take and one take only. There’s some serious shouting on that song, and Paul was taking care to protect his voice; several takes might do damage that would take time to heal.

Six years earlier, when the lads were recording their first album, they did the whole thing — fourteen songs — in one day, and they saved “Twist and Shout” for the end because John knew that once he had done that one, he wouldn’t have any voice left to do anything else.

Ortega y Gasset’s entire essay [on “The Dehumanization of Art”] is brilliant, and should be required reading in college humanities programs — it’s more relevant now than ever before…. But instead it’s almost never read. Instead, grad students are assigned Walter Benjamin’s essay from 1935 on “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction” — which embraced mass production as a “progressive” way to provide “visual and emotional enjoyment” in an “intimate” manner to millions of people. I have sympathy for Benjamin, but he was betrayed by the mass producers — much as we are getting betrayed by today’s tech overlords of creative ‘content’.

A great post by Mr. Gioia, and consistent with my recent comment that a Ruskinian account of contemporary culture must begin by attending to beauty. And we might begin that endeavor by considering Aphorism 19 from Ruskin’s Seven Lamps of Architecture: “All beauty is founded on the laws of natural forms.”

What follows is a kind of sequel to the introduction to Ruskin I published several years ago.

Ruskin begins The Stones of Venice by identifying what he believes to have been the essential characteristics of Venetian society in its heyday – which is to say, the twelfth century through the fourteenth:

The most curious phenomenon in all Venetian history is the vitality of religion in private life, and its deadness in public policy. Amidst the enthusiasm, chivalry, or fanaticism of the other states of Europe, Venice stands, from first to last, like a masked statue; her coldness impenetrable, her exertion only aroused by the touch of a secret spring. That spring was her commercial interest, — this the one motive of all her important political acts, or enduring national animosities. She could forgive insults to her honor, but never rivalship in her commerce; she calculated the glory of her conquests by their value, and estimated their justice by their facility.

Yet even as they calculated in this crassly financial way,

The habit of assigning to religion a direct influence over all his own actions, and all the affairs of his own daily life, is remarkable in every great Venetian during the times of the prosperity of the state; nor are instances wanting in which the private feeling of the citizens reaches the sphere of their policy, and even becomes the guide of its course where the scales of expediency are doubtfully balanced.

Ruskin goes on to say (somewhat wryly, I think) that this influence of private piety on public policy only happened when the leaders of Venice were rushed — whenever they had time to think they would suppress piety in favor of commercial self-interest.

Nevertheless, the piety of the great Venetians — and Ruskin believes it was sincere, that these men were not hypocrites but rather inconstant and/or skilled in compartmentalizing (as who among us is not?) — seemed to have the power to shape the city’s spirit and to sustain its prosperity, because “the decline of her political prosperity was exactly coincident with that of domestic and individual religion.” When that religion waned, so too did Venice’s political and commercial influence. Ruskin explains that precise correspondence between private piety and public success thus:

We find, on the one hand, a deep and constant tone of individual religion characterising the lives of the citizens of Venice in her greatness; we find this spirit influencing them in all the familiar and immediate concerns of life, giving a peculiar dignity to the conduct even of their commercial transactions, and confessed by them with a simplicity of faith that may well put to shame the hesitation with which a man of the world at present admits (even if it be so in reality) that religious feeling has any influence over the minor branches of his conduct. And we find as the natural consequence of all this, a healthy serenity of mind and energy of will expressed in all their actions, and a habit of heroism which never fails them, even when the immediate motive of action ceases to be praiseworthy. With the fulness of this spirit the prosperity of the state is exactly correspondent, and with its failure her decline, and that with a closeness and precision which it will be one of the collateral objects of the following essay to demonstrate from such accidental evidence as the field of its inquiry presents.

And he pauses at this point in his exposition to suggest that this history might have some relevance to British subjects who have ears to hear. The idea that London is the New Venice is a muted but constant refrain in The Stones of Venice.

This account of politics and religion in Venice is quite interesting, but the thing that makes Ruskin Ruskin is where his thought now takes him: “I would next endeavor to give the reader some idea of the manner in which the testimony of Art bears upon these questions, and of the aspect which the arts themselves assume when they are regarded in their true connexion with the history of the state.” And this is what the rest of The Stones of Venice, all three big volumes of it, does: to explain how the art of Venice — its painting, its architecture, its ornaments and designs in every medium — reveals the rise, the health, the majesty, the decline, and the humiliation of the city of Venice. Which is, I think it’s fair to say, an astonishing project.

The question I keep asking myself — that I’ve been asking myself for years — is: How can I think in a genuinely Ruskinian way about our own time and place? What would that look like? What would be the … I dunno, the ingredients I guess? The only thing I know for sure — and this goes back to the last sentence of my earlier Ruskin essay — is that we must begin by attending to beauty, and to the absence of it, in our public life. But that’s an abstract answer to a question that demands specificity.

The perception of colour is a gift just as definitely granted to one person, and denied to another, as an ear for music; and the very first requisite for true judgment of Saint Mark’s, is the perfection of that colour-faculty which few people ever set themselves seriously to find out whether they possess or not. […]

The fact is, that, of all God’s gifts to the sight of man, colour is the holiest, the most divine, the most solemn. We speak rashly of gay color and sad color, for color cannot at once be good and gay. All good color is in some degree pensive, the loveliest is melancholy, and the purest and most thoughtful minds are those which love colour the most.

– John Ruskin, The Stones of Venice

Ruskin thought about color all the time, and wrote about it often. See for instance this post. He seems to have thought color itself a mystical and revelatory thing, something he was surprised and delighted that God took the trouble to create.

In his poem “Little Gidding,” written during World War II, T. S. Eliot wrote that the Cavaliers and Puritans who fought in England’s Civil War, in the 17th century, now “are folded in a single party.” The same already seems true of Vendler and Perloff. Today college students are fleeing humanities majors, and English departments are desperately trying to lure them back by promoting the ephemera of pop culture as worthy subjects of study. (Vendler’s own Harvard English department has been getting a great deal of attention for offering a class on Taylor Swift.) Both Vendler and Perloff, by contrast, rejected the idea that poetry had to earn its place in the curriculum, or in the culture at large, by being “relevant.” Nor did it have to be defended on the grounds that it makes us more virtuous citizens or more employable technicians of reading and writing.

Rather, they believed that studying poetry was valuable in and of itself.

I like this essay, but I’m mentioning it here because Kirsch makes use of a common phrase that has always puzzled me: “valuable in and of itself.” Variants: “intrinsically valuable” and “valuable for its own sake.” I have never known what that means — or even could mean. Because: if you ask people to say more about valuing something for its own sake, they end up saying that it gives them pleasure or delights them or fascinates them. But to pursue something because it delights or fascinates you is not pursuing it for its own sake — it’s pursuing it for the sake of the delight or fascination.

When people say that something is “valuable in and of itself,” I think what they mean is simply that it has no economic or social value — note Kirsch’s contrast between intrinsic value and something valued because it “makes us more virtuous citizens or more employable technicians of reading and writing.” Someone might say that when we say some artifact or experience is intrinsically valuable we’re saying that it does not have any instrumental value — but isn’t a song that delights me instrumental to that delight? And isn’t that okay?

So I think that when we describe something as having intrinsic value, what we really mean is that the value it provides is higher than or nobler than any furthering of crassly economic or social ambitions. We’re indirectly and somewhat sloppily appealing to a hierarchy of goods. And maybe — especially in the context of debates about liberal education, which is at least partly the context of Kirsch’s essay — we should be more explicit about that, and conscious of what our hierarchy is and why we affirm it.

Russell Lynes’s 1949 essay for Harper’s, “Highbrow, Lowbrow, Middlebrow” — about which I’ll have more to say later — features this illustration by Saul Steinberg.

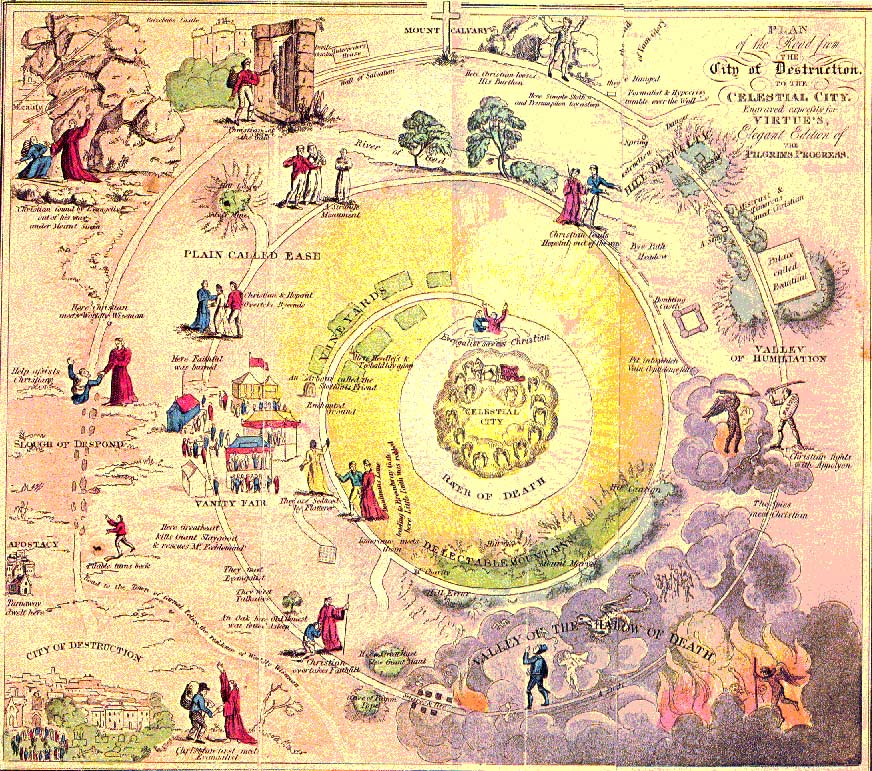

I’ve been teaching The Pilgrim’s Progress, something that always gives me great joy. I find it simply wonderful that so utterly bonkers a book was so omnipresent in English-language culture (and well beyond) for so long. You couldn’t avoid it, whether you loved it — as George Eliot’s Maggie Tulliver did, and lamented the sale of the family’s copy: “I thought we should never part with that while we lived” — or found it puzzling, as Huck Finn did when he recalled the books he read as a child: “One was ‘Pilgrim’s Progress’, about a man that left his family it didn’t say why. I read considerable in it now and then. The statements was interesting, but tough.”

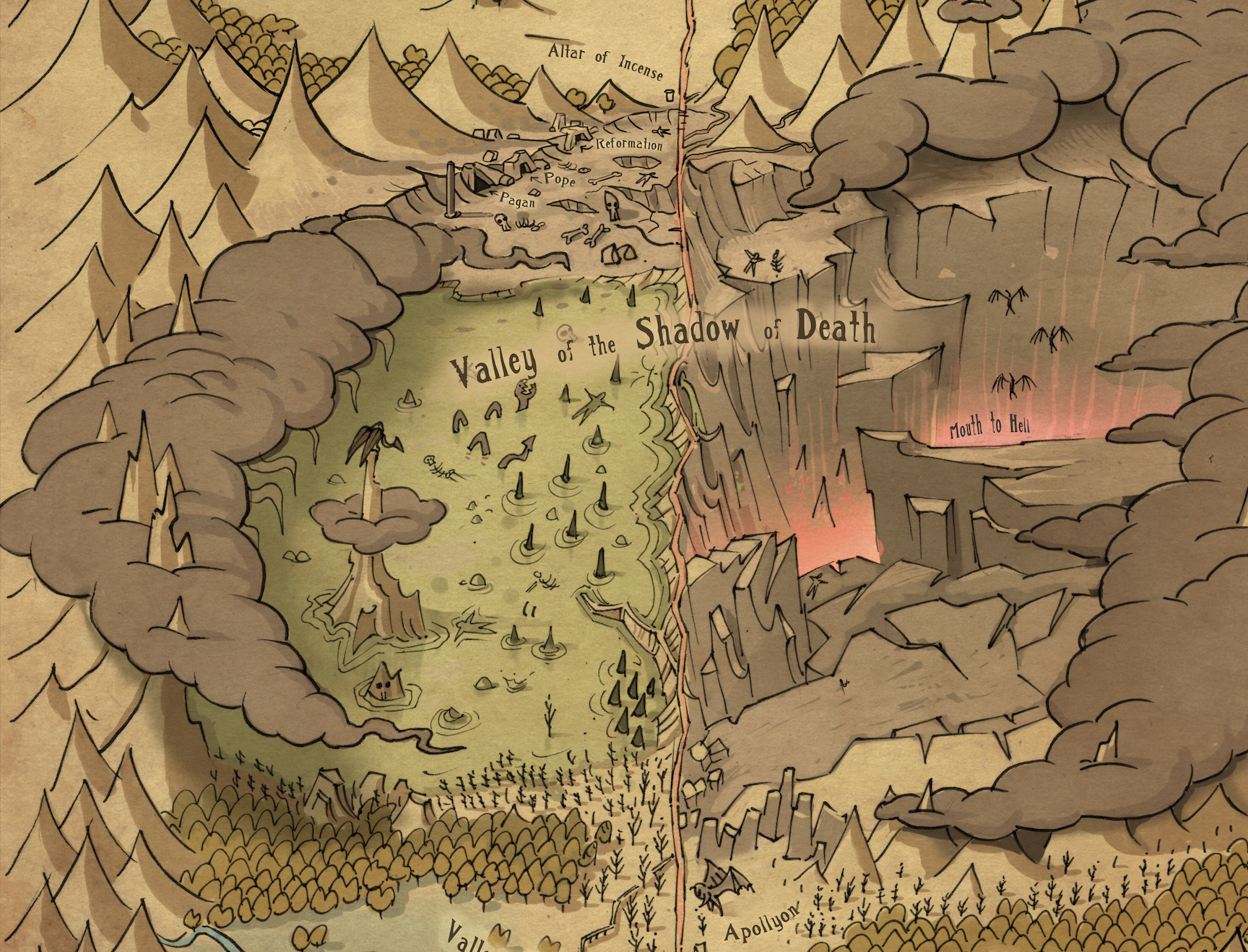

One of the “tough” things about the “statements” is the way they veer from hard-coded allegory to plain realism, sometimes within a given sentence. One minute Moses is the canonical author of the Pentateuch, the next he’s a guy who keeps knocking Hopeful down. But the book is always psychologically realistic, to an extreme degree. No one knew anxiety and terror better than Bunyan did, and when Christian is passing through the Valley of the Shadow of Death and hears voices whispering blasphemies in his ears, the true horror of the moment is that he thinks he himself is uttering the blasphemies. (The calls are coming from inside the house.)

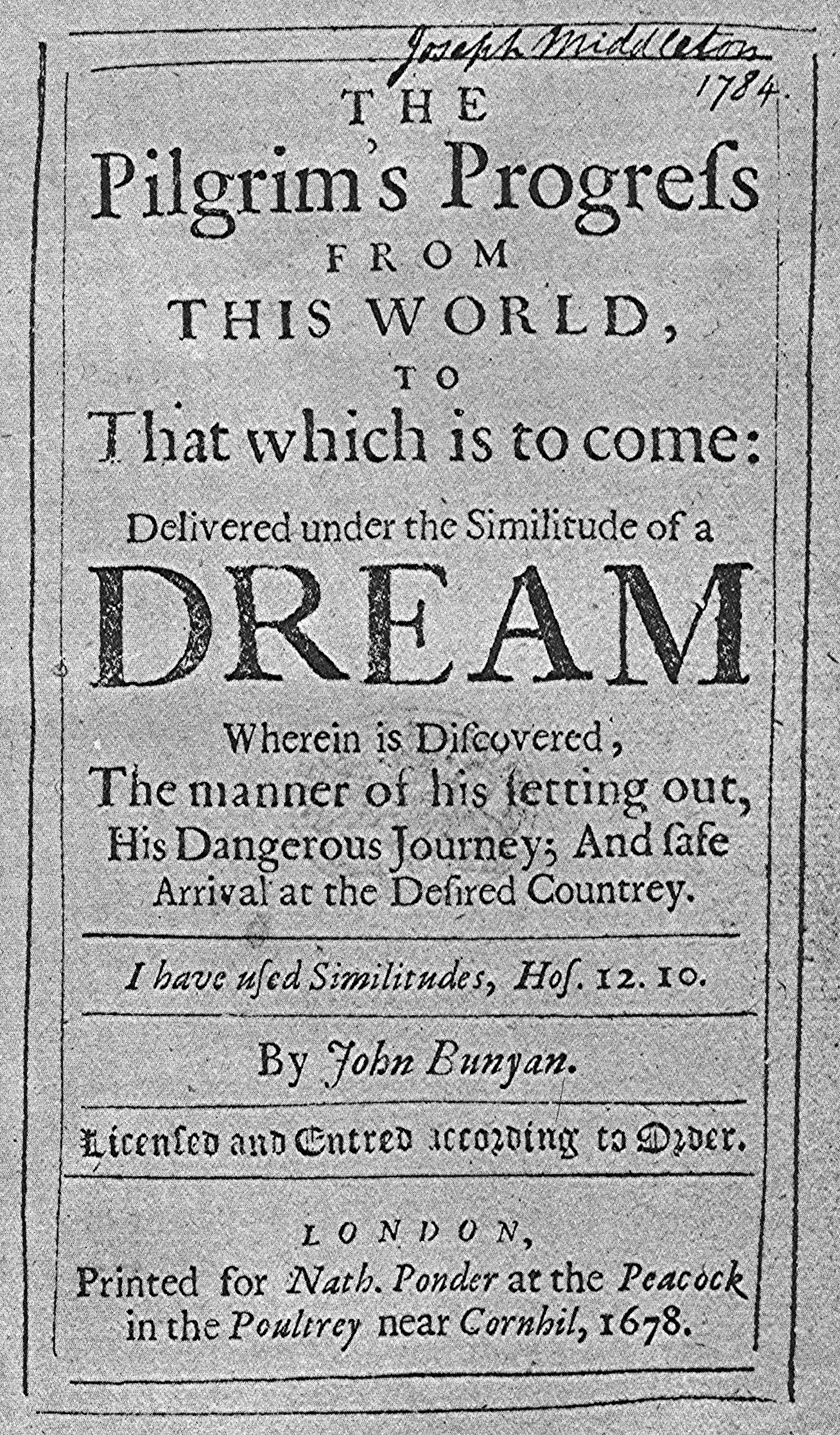

It seems likely that the last major cultural figure to acknowledge the power of Bunyan’s book is Terrence Malick, who begins his movie Knight of Cups with a voice declaiming the full title of the book: “The pilgrim’s progress from this world to that which is to come, delivered under the similitude of a dream; wherein is discovered the manner of his setting out, his dangerous journey, and safe arrival at the desired country.”

Those words are uttered by John Gielgud, because they are taken from a 1990 performance of Ralph Vaughan Williams’s The Pilgrim’s Progress: A Bunyan Sequence, which is a work that Vaughan Williams wanted to compose for his whole life, but only got to near his life’s end: it is his final operatic composition. And it’s wonderful.

The Pilgrim’s Progress is almost always illustrated, and prominent among those illustrations are maps. Here’s a post about those maps. From that post I learned that Garrett Taylor — an artist and animator who has worked for Pixar and on The Wingfeather Saga TV series — has mapped The Pilgrim’s Progress is four prints that you can buy here. I bought them and had them framed and they now adorn a wall of our house. I stop to look at them three or four times a day.

It would be wrong for me to post the full-resolution images here, but I think I can risk one portion of one image:

Now, if Mr. Taylor can just convince Pixar to film the whole book….

In my Christian Renaissance of the Twentieth Century class, we’re reading, back-to-back, passages from Jacques Maritain’s Art and Scholasticism (1920) and Karl Barth’s 1922 lecture “The Word of God and the Task of Theology” (reprinted in this excellent collection of writings by Barth, edited by Keith Johnson). It’s interesting to compare these two vital figures, because their tasks are in some ways quite different but in other ways very similar.

It is noteworthy, first of all, that Maritain and Barth, born just four years apart, grew up in a generally liberal Protestant world, a mild environment in which pietism and evangelicalism were either embarrassing or totally unknown, and Catholicism known but alien and unthinkable.

Barth’s lecture was given in response to critics of his great commentary on Romans, and is basically a defense of his “dialectical” method against the gentle anthropological pieties of liberal Protestantism. He wants German Protestants to realize that their project is doomed: it is neither fish nor foul, neither fully Christian nor fully secular; it is mealy-mouthed, tepid, timorous. Nietzsche had made the same point several decades earlier in his evisceration of David Strauss, but Nietzsche wanted the pastors and theologians to cast aside the last vestiges of supernaturalism and move forward boldly into a world freed from the “slave morality” of Christianity. (This move forward is also a move backward in the sense that Nietzsche wants to draw on the energies of a long-marginalized paganism, a paganism ripe for renewal and a final victory over Jewish and Jewish-inspired thought.)

Barth also wants theology to move both forward and backward: forward fearlessly into a modernity which has no time for warmed-over moralism, and backward to reclaim the radical and essential insights of Luther and Calvin. We have to be as fearless as Luther and Calvin, he thought, if we are to speak convincingly to the watered-down world liberal Protestantism had (largely inadvertently) created.

Maritain’s challenge to his readers is similar in that he believes that figures from the Christian past, especially Thomas Aquinas, speak to modernity more powerfully and effectually than any self-proclaimed “modernist” theologian or priest possibly could. But in another sense he has a very different problem than Barth — and the problem arises largely because Maritain is interested in the renewal of art.

Once he became a Catholic, Maritain entered a church that for the previous century had not been following the liberal Protestant line of cultural accommodation — reconciling itself to its cultured despisers — but rather had been doing something like the opposite: insulating itself, protecting itself, from modernity. Thus the famous last item in Pio Nono’s Syllabus of Errors: “The Roman Pontiff can, and ought to, reconcile himself, and come to terms with progress, liberalism and modern civilization.” (Pio Nono: Nope.)

For Maritain this is in one essential sense vitally correct, indeed necessary to the survival of Catholicism. But Maritain knows that however necessary such self-protection may be, it can lead to a generalized prejudice against the new and different. So in this little book he takes pains to insist that even by the standards we acquire through the study of medieval Scholastic thought, Stravinsky and Satie are outstanding composers whose music is worth our most serious attention. (He struggles a bit with certain visual artists, and I may do a post on that.)

So, in short: Barth wants to lead liberal Protestantism away from an accommodationist tendency that had become sheer cultural capitulation, while Maritain wants to lead orthodox Catholicism away from its tendency to mere reaction against the new, to reflexive revulsion. But both of them think that the cure for the intellectual diseases of their ecclesial communities is: Ad fontes! Back to the sources!

David Brooks: “Does consuming art, music, literature and the rest of what we call culture make you a better person?” Answer:

But, okay, there’s more to say. Anything we experience may, depending on the circumstances, help to make us better people, but we have to be disposed to change, willing to change for the better. And maybe one thing art can do is to shape our dispositions, put us in a frame of mind or heart to live differently. (That’s what happened to Maggie Tulliver when she read The Imitation of Christ, which is not a work of art exactly but is a book artfully shaped.)

I still think one of the most useful approaches to this whole set of questions is Nick Wolterstorff’s early book Art in Action. Here’s a quote:

What then is art for? What purpose underlies this human universal?

One of my fundamental theses is that this question, so often posed, must be rejected rather than answered. The question assumes that there is such a thing as the purpose of art. That assumption is false. There is no purpose which art serves, nor any which it is intended to serve. Art plays and is meant to play an enormous diversity of roles in human life. Works of art are instruments by which we perform such diverse actions as praising our great men and expressing our grief, evoking emotion and communicating knowledge. Works of art are objects of such actions as contemplation for the sake of delight. Works of art are accompaniments for such actions as hoeing cotton and rocking infants. Works of art are background for such actions as eating meals and walking through airports.

Works of art equip us for action. And the range of actions for which they equip us is very nearly as broad as the range of human action itself. The purposes of art are the purposes of life.

I think these statements provide a great entry into the conversation about what art does and is, because they make the notion of “becoming a better person” less abstract. A mother whose lullaby soothes her baby and also calms herself is, perhaps, making herself a better person in that context, at that moment.

Brian Eno, from a 1995 diary entry:

Whatever you now find weird, ugly, uncomfortable and nasty about a new medium will surely become its signature. CD distortion, the jitteriness of digital video, the crap sound of 8-bit – all these will be cherished and emulated as soon as they can be avoided.

It’s the sound of failure: so much of modern art is the sound of things going out of control, of a medium pushing to its limits and breaking apart. The distorted guitar is the sound of something too loud for the medium supposed to carry it. The blues singer with the cracked voice is the sound of an emotional cry too powerful for the throat that releases it. The excitement of grainy film, of bleached-out black and white, is the excitement of witnessing events too momentous for the medium assigned to record them.

Wish I had seen this before I wrote my “Resistance in the Arts” essay. But I think if I had read a lot more Eno I probably wouldn’t have felt the need to write the essay at all.

Criticism of this kind is a misuse of learning to muddle discussion for the sake of scoring points rather than to clarify it for a curious public. There is plenty of intelligent and reasonable criticism of Wilson’s work to be had from people who know the poems well — the Bryn Mawr Classical Review was positive but not uncritical, and I myself think her choices at Odyssey 15.365 were the wrong ones — and there is no need to give credence to people who consider their own desire for attention an adequate substitute for the knowledge and consideration that must attend real critical judgment.

This is well said. To almost everyone writing about art today I want to say: Dragging every scholar, every critic, every translator, every artist, every artwork before the bar of your political tribunal might, just conceivably, not be the only or even the best thing you can do when confronted by a work of art.

I don’t think we’ve ever needed genuine works of art — imaginative creations that press us to see the world in larger or at least different ways than our standard everyday media-navigation categories allow — more than we do now. But our current resources are few, because of the ways the major art-related organizations have lost any discernible sense of purpose. They are merely reactive to social-media pressure. Examples:

In light of these developments I’ve come to believe that the most important thing I can do here on this blog is to write about art as art — which is not to say that art lacks political purposes and implications. Often it is powerfully political. But no artwork worthy of our attention approaches politics the way that journalists and people on X do, as a matter of checking the right boxes to avoid exclusion from the Inner Ring. One thing good art always does is to remind us that our experience is dramatically larger than our quotidian political categories suggest. We are unfinalizable; we sprawl. The failure to recognize that is a terrible disease of the intellect.

I am finished — not altogether, but largely, I think — with political and cultural disputation. I want to write about works of art that transcend the box-checking, that thwart easy dismissals, that shake us up. And if the current art scene doesn’t offer any of that, then I can always continue to break bread with the dead.

The essay that I published earlier this year on “Resistance In the Arts” was largely inspired by my reading of one book, Ian MacDonald’s simultaneously maddening and magisterial Revolution in the Head: The Beatles’ Records and the Sixties. It’s important to to pay attention to that subtitle. McDonald wants to argue that the music that the Beatles made exemplifies the cultural movement that we call “the Sixties” better than anything else does, and he makes a very good case for that idea, in which I’m quite interested. But I’m even more interested in the final words of the actual narrative of the book, words written by way of introduction to a chronology of the 1960s. (That chronology, which serves as an appendix to the book, consists of four columns: what the Beatles were doing; what else was happening in pop music in the UK; key political and social events; and developments in the arts more generally — for instance, cinema, jazz, classical music, poetry, etc.) Here’s what MacDonald says to conclude his narrative and introduce that chronology:

There is a great deal more to be said about the catastrophic decline of pop (and rock criticism) — but not here. All that matters is that, when examining the following Chronology of Sixties pop, readers are aware that they are looking at something on a higher scale of achievement than today’s — music which no contemporary artist can claim to match in feeling, variety, formal invention, and sheer out-of-the-blue inspiration. That the same can be said of other musical forms — most obviously classical and jazz — confirms that something in the soul of Western culture began to die during the late Sixties. Arguably pop music, as measured by the singles charts, peaked in 1966, thereafter beginning a shallow decline in overall quality which was already steepening by 1970. While some may date this tail-off to a little later, only the soulless or tone-deaf will refuse to admit any decline at all. Those with ears to hear, let them hear.

So that’s MacDonald’s blunt assessment. And what launched my essay was a double response to that paragraph. On the one hand, I thought that in relation to pop music, he is 100% correct. But the sweeping judgment I have highlighted, about “the soul of Western culture,” is less readily defensible. He wrote those words in the mid or late 1990s. In retrospect, it seems to me that classical music was in a much, much better place in the 1990s than it had been in the 1960s; similarly, the architecture of the Nineties was significantly more varied and inventive than architecture in the Sixties, partly as a result of certain technical changes, including CAD (computer-assisted design). I could give other examples.

Thus MacDonald’s Grand Narrative about Western culture — his assumption that Western culture is one giant, uniform Thing that is always on a single trajectory, either ascending or descending — is just nonsense, if also an all-too-common form of nonsense.

But: at any given moment in history in any given location, certain specific arts may operate at a higher level than they do at other times, or in other places. So I began my essay by noting how much better English drama was in the period between 1590 and 1620 than it ever had been before or ever would be again — and that is true even if you factor Shakespeare out of the equation. (You still have Marlowe, Webster, Jonson, Beaumont & Fletcher, etc.) Ditto the outpouring of genius in pop music between, say, 1962 and 1975, an outpouring that’s astonishing even if you factor the Beatles out of the equation. And what such stories suggest, or anyway what they suggest to me, is that circumstances can conspire to make a particular art form more dynamic at some moments than it is at others.

I’m not sure that I made myself perfectly clear in that essay. I’m a bit frustrated with it. But I still think that the chief point that I was pursuing is an absolutely vital one. We need to think about what kinds of circumstances encourage outstanding art and what kinds militate against outstanding art. In the essay I argued that there must be a balance between forces that enable and forces that resist, and that that balance is at once technological, economic, and social. You have to be able to do and make certain things, but the making should not be too easy, just as you should not be totally blocked from achieving what you’re trying to achieve. I mentioned the Beatles song “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which creates special effects through the use of five tape loops, loops which are placed within the song in a cunningly designed sequence. The loops (made by Paul McCartney on a tape recorder he had at home) were not easy to create, which is why there were only five of them; but five turned out to be the perfect number, because that allowed both repetition and variation, both of which are key to successful art. Moreover, while the Beatles were free to add those tape loops to the song, they were not (yet) free to spend six months in the studio or to make 10-minute songs.

The Beatles were immensely talented, to be sure, and were surrounded by equally talented support in the producer George Martin and the engineer Geoff Emerick; but Taylor Swift is also extremely talented and knows how to surround herself with gifted producers, engineers, and musicians, and yet, for all her enormous popularity, she isn’t changing the face of music. Her musical language is basic and predictable: given any two consecutive chords of a Swift song, the listener can predict with a high degree of confidence what the next one will be. She has not, to my knowledge, written or performed a single song that alters even in the tiniest way the landscape of pop music, while, by contrast, there was a period of five years during which the Beatles were doing that every few weeks. Maybe those conditions simply can’t be recreated; maybe Taylor Swift, and indeed everyone working in the aftermath of the Beatles’ meteoric career, is, in Harold Bloom’s term, belated. But, on the other hand, maybe we’re too quick to accept belatedness.

One of the reasons we still listen to the Beatles (one of the reasons we still read or watch Shakespeare) is that for them, in their time and place, they discovered the ideal balance between enablement and resistance; the stars aligned for them. (When the Beatles broke up the stars went out of alignment, forever; even if John Lennon had lived and the band had reassembled, they wouldn’t have been able to come close to what they achieved in the Sixties. The balance of resistances had altered, and for the worse.) I tried — and, I think, failed — to figure out what specifically it looks like when the stars so align for artists, and then to go beyond that to ask a question: Is there anything that we can do to help those stars to align?

You know, when absolutely staggering greatness shows up, I don’t think we can pay too much attention to it. We should not just look at it and applaud it, but also try to ask ourselves, in the most serious and intense way possible, What enabled that, and how can we enable something else that’s equally great?

I don’t know the answers to those questions, but I keep thinking about a tossed-off comment in Ian MacDonald’s book. He’s writing about a song that John and Paul wrote together — I don’t remember which one, but it doesn’t matter — and in that song there’s a moment when the standard, the expected, harmonic progression calls for an A major chord — but the Beatles go to A minor instead. Many sophisticated musicologists, MacDonald says, have studied this moment and written with analytical rigor about the harmonic language the Beatles employ at this moment and the different ways one might conceptualize it. But that’s all wrong, MacDonald says.

The key point is this: John and Paul were sitting in a room and each of them had a guitar on his lap. That’s the thing to remember, because every guitar player knows how much easier it is to play an A minor chord than an A major one — and, even more important, how much easier it is to riff on an A minor chord, to introduce hammer-ons and pull-offs that make the song sound better. (This is true when using standard tuning anyway — what I like to call Em7add11 tuning — which the Beatles almost always did.) Almost certainly, MacDonald says, at the moment when the A major chord would’ve been the most obvious thing in the world to play, either John or Paul went to the A minor instead — and lo and behold, it sounded cool. So they kept it.

Handmind at work.

You have to remember that neither of those guys could read music; neither of them wanted to read music. Nor did they have access to modern digital tools for music creation. What did they have? Four things:

And those were the tools they needed.

And maybe that’s Step One. If we want to reinvigorate the arts, if we don’t want culture to come to a standstill, maybe we need to start with a radical minimalism. Artists: deprive yourselves of everything except the absolutely essential tools. You can’t stream, you can’t use a DAW, you can’t look anything up online, you don’t have an iPad. You have your sensorium and you have the most basic tools imaginable — a pencil, a lump of clay, a pennywhistle or a ukelele. Go.

Many spoilers follow.

Wes Anderson’s Asteroid City begins with a framing story: We seem to be watching a television show from the 1950s, and in that show our Host — something like the Stage Manager from Our Town — presents to us a new play called Asteroid City. From time to time we return to this framing story, in which we learn (in nonconsecutive order) how a playwright named Conrad Earp came up with the idea for his play, how the play was cast, how changes were made to it, how its director came to live backstage amid the props, and so on. We’re even told that the playwright died in an accident.

The play itself is presented to us in full color, featuring a slightly more-pastel-than-usual version of the typical Wes Anderson color palette. Though, as noted above, there is a backstage, and at one point we even see an actor leave the scene he’s playing to go backstage and ask the director whether he’s playing his part properly, the moment we’re placed within the world of the play we’re given a 360º camera rotation — in 90º increments: quarter-turn, stop; quarter-turn, stop; etc. — to demonstrate that the play’s world completely surrounds us, that for us there should not be, cannot be, any “backstage.”

Here’s what happens. It’s 1955. Many people converge on a meteor crater in the desert somewhere near the convergence of California, Arizona, and Nevada. Some teenage student scientists, along with their parents, have come to receive awards (from a general in the U.S. Army) for their inventions; a busload of younger students are there on a field trip; a country-and-western band get stuck when they miss their bus out of town. (Or “town” — the population is 87.) In the middle of the award ceremony a spaceship arrives and hovers over the crater; an alien descends from the ship and takes a basketball-sized chunk of the meteorite; the government confines everyone to the site for a week and forbids communication with the outside world. Tentative romantic relationships begin. One of the teenage scientists manages to get word out to his high-school newspaper; with the information embargo broken, the government decides to let everyone go home; before everyone can leave the spaceship returns to drop off the meteorite; the general re-imposes lockdown; chaotic resistance ensues; the actor has his motivational crisis and goes backstage; the lockdown is lifted; everyone goes home. So it’s a comedy, basically.

Or not. Many of Wes Anderson’s movies are tonally awkward, and this one more than most. The awkwardness here arises from one major plot point that I have omitted. That actor who has a crisis about his motivations? He’s playing a photojournalist named Augie Steenbeck … hang on. Let’s pause a moment to pursue clarity. You’ll see a lot of commentary on this movie saying that Jason Schwartzman plays Augie Steenbeck. This is not true. In the movie Asteroid City Jason Schwartzman portrays an actor named Jones Hall who, in the play Asteroid City, portrays a photojournalist named Augie Steenbeck who visits a town called Asteroid City. All clear now? Okay.

Well … perhaps I should add that, depending on how you understand this TV-show framing, it’s possible that Jason Schwartzman is playing an unnamed actor who, for the purposes of television, is playing the stage actor Jones Hall, who plays the photojournalist Augie Steenbeck. But let’s pretend I didn’t say that.

Augie Steenbeck has come to Asteroid City because his son Woodrow is one of the teenage scientists to be honored. He brings Woodrow and also his three younger daughters. He has a big problem, though: his wife, the mother of his four children, has been dead for three weeks and he hasn’t told them. Now, under pressure from his father-in-law, whom he talks to on the phone, he decides to tell them — and does, in the flat tones that all of Wes Anderson’s characters typically use, while holding her ashes in a Tupperware container.

Jones Hall, the actor playing Augie, doesn’t understand Augie. He’s doesn’t know what’s going on his Augie’s head — that emotionless flatness of tone hides Augie from the man performing him. He’s also confused about some of Augie’s actions, especially one odd thing: after he convinces Conrad Earp to cast him as Augie, he asks “Why does Augie burn his hand on the Quickie Griddle?” (Quickie Griddle pictured above, at the bottom of the frame. Augie is just about to touch it.) Augie has toasted a sandwich, and when talking to the woman he may be falling for, he suddenly places his palm on the hot griddle. But Conrad Earp doesn’t know why Augie does that: “He just sort of did it while I was typing.” Hall’s ongoing puzzlement about Augie then takes him backstage to talk to the director. “I still don’t understand the play,” he says. “Doesn’t matter,” the director replies. “Just keep telling the story.”

Hall is not satisfied. The big chaotic scene of resistance to the general’s diktat is still going on, and he doesn’t think he’ll be missed if he stays away a few moments longer. “I need some fresh air,” he says, to which the director replies, “You won’t find any.” But Augie goes out on the fire escape anyway and lights a cigarette.

•

Think of a movie like The Grand Budapest Hotel. How might one defend treating a subject like the Bloodlands of the mid-twentieth century in this peculiar way, with its chocolate-box colors, farcical action, exaggerated and anti-naturalistic acting styles? Asteroid City is, I think, Wes Anderson’s attempt to answer that question. That’s what I’m slowly getting around to explaining.

•

We primarily see Augie interacting with Midge, the woman he may be falling for, as they look at each other across the gap that separates his tiny motel cottage from hers. Each of them is framed for the other; they speak but are separated by the walls. And now, when Jones Hall goes out onto the fire escape, he finds himself immediately opposite another fire escape, one attached to another theater, and he is looking at another actor, another person who has left the theatrical space for some fresh air and a smoke — and it’s a person he recognizes. “Ah,” he says, it’s you, the wife who played my actress.” The inadvertent switch of nouns is of course telling.

In some earlier version of the play Asteroid City Conrad Earp had written a scene between Augie and his wife, a scene in which she advises him how to navigate his life without her. Jones Hall has forgotten the scene, but “the wife who played his actress” remembers it word for word, and quietly recites it to him as they look at each other across their respective fire-escape platforms. Jones Hall has traveled from the brightly-colored environment of Asteroid City to the disorderly backstage collection of props and makeup to what is for him the “real world” — the world of “fresh air.” Was the director wrong to tell him he wouldn’t find any?

What’s the opposite of “fresh”? One opposite is artificial, and it’s noteworthy that the actress who recites her discarded lines, her discarded part, is dressed for a period drama, wearing the rococo costume of a seventeenth-century aristocrat. Jones Hall learns something he needs to know about his character not through inhaling fresh air, not through re-entering the “real world,” but through a chance encounter with words of explanation, words rejected because they were too explicit, because they said too much — and delivered to him by a Goddess of Contrivance, the very embodiment of artifice.

Again, this is all part of the frame story, and the final part part of the frame story involves a flashback to a visit paid by Conrad Earp to a place very like the Actors Studio, an institution created in the very period in which our story is set. There Conrad Earp and the movie’s equivalent of Lee Strasberg encourage the actors gathered there — several of whom eventually make up the main body of the cast of the play Asteroid City — to “workshop” the dialogue of the play. Some of them enter, or feign to enter, a kind of trance state, in the midst of which the camera closes in on Jones Hall, who looks directly at us and says a single sentence, a sentence then taken up and chanted by the whole room: “You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep.”

You can’t wake up if you don’t fall asleep. I think this is as close as Wes Anderson has ever come to explaining and defending his very peculiar style of filmmaking. What he’s telling us is that the most vital and the most painful things in life cannot be confronted directly, explicitly, artlessly. There must be masks — contrivances, artifice — that distract us, lull us, distract our agitated minds. As Touchstone says, “The truest poetry is the most feigning.” Tragic experience, to be properly worked through, must wear the mask of comedy. And perhaps for the deepest griefs a single mask is insufficient; you may need several. So here we see layer after layer being peeled away, but no matter how many layers we remove we just find more artifice.

And I think this is Anderson saying that he wants to make art about some of the most profound of human experiences — but doesn’t know how to make it explicitly and directly about those experiences. Or doesn’t want to. Or doesn’t believe in doing so. In some ways, then, you can see this movie as a kind of a commentary on his other films, above all, I think, The Grand Budapest Hotel. If you want to know why Wes Anderson takes such a mannered and apparently frivolous attitude towards matters of the greatest depth and significance, I think he’s explaining that in Asteroid City. He’s obeying Emily Dickinson’s instruction to “Tell the truth but tell it slant.” And he’s doing that because, as the bird says, “human kind / Cannot bear very much reality.”

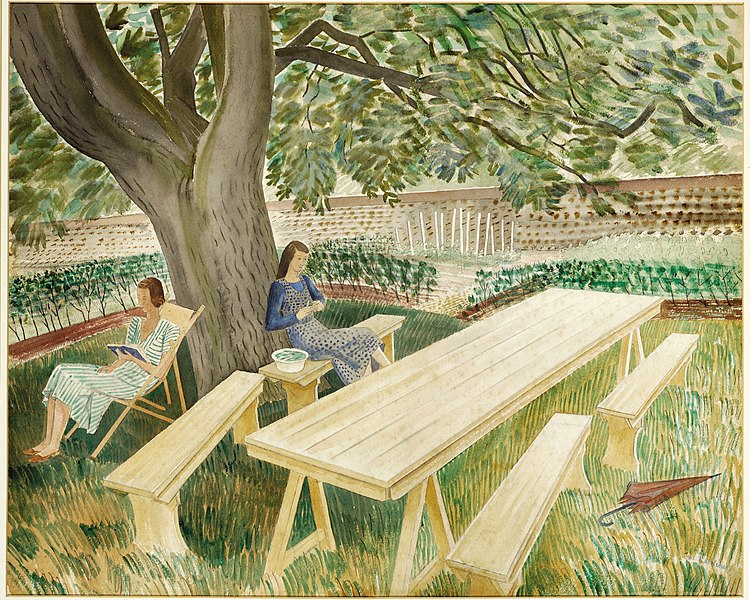

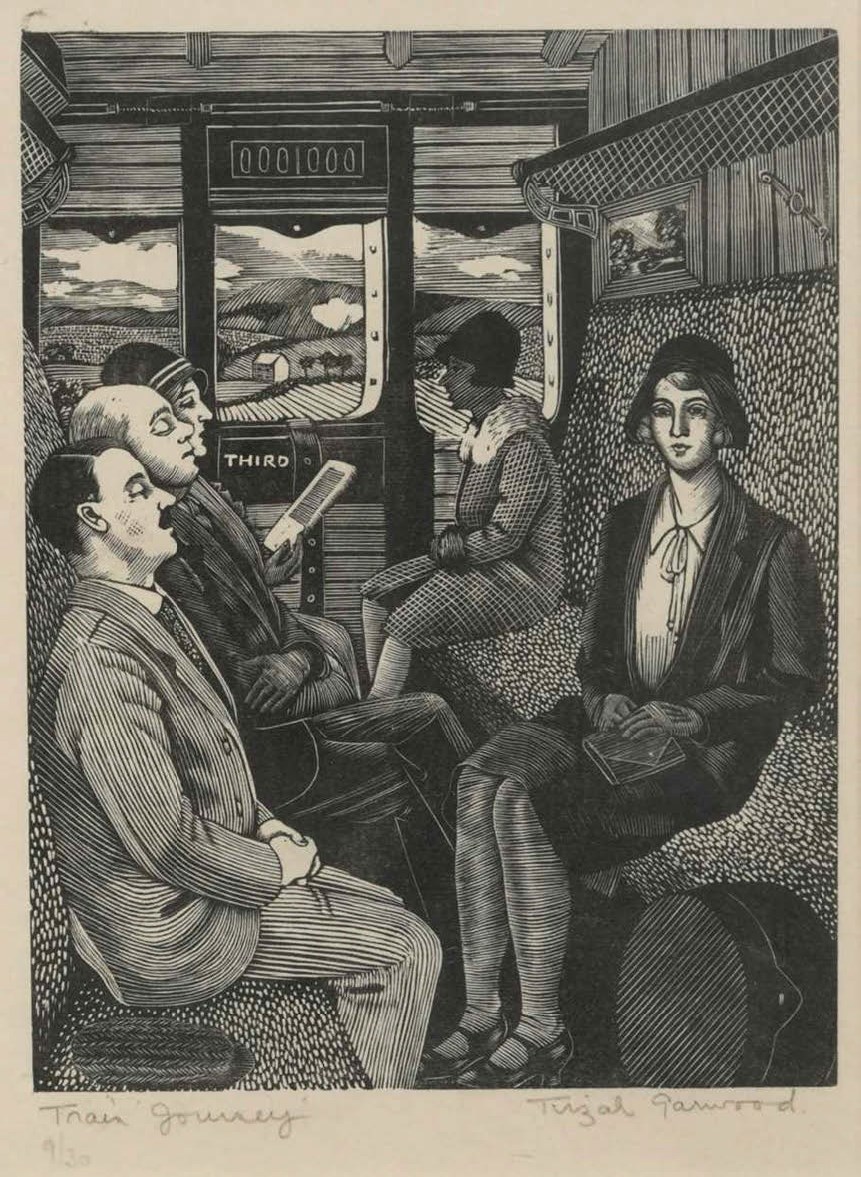

Regular readers of this will know of my fondness for the art of Eric Ravilious. Ravilious was married to another highly gifted artist, Tirzah Garwood, whose work I have posted a couple of times; but she deserves more attention than I have given her. (In the Ravilious painting above, that’s her on the right, accompanied by her friend Charlotte Bawden. I will write at some point later about the Bawdens, Charlotte and Edward.) Here they are together:

Here’s something of a self-portrait:

(Compare Ravilious’s “Train Landscape.”) Garwood worked in several media, and when you look at the image below you’ll wish she had done more in that curious medium, embroidery.

(Also perhaps a bit of a self-portrait?) Larger version here.

Alas, neither Eric nor Tirzah were blessed with long life. In the Second World War Eric was an official “War Artist,” and in August 1942 his plane was lost somewhere over Iceland. He was 39. Tirzah suffered from recurrent cancer and died in 1951 at the age of 42. Their three children survived them, and their youngest, Anne Ullmann (born 1941), still celebrates and advocates for her parents’ work.

A brilliant, angry, nearly-despairing essay by Justin Smith-Ruiu, one that grows out of a reading of William Gaddis’s brilliant, angry, almost-completely-despairing novel JR:

Is there any more vivid expression of the reduction of lived reality to two-dimensional catchphrases than the one conveyed in a sentence beginning with, “Speaking as an X …”? Our entire social reality is built up out of catchphrases now, and the people who really ought to be criticizing this nightmarish condition have instead abnegated their duty as intellectuals and have taken on the task of enforcing the repetition of certain catchphrases and of muffling other ones. And there is really no one left to perform that last doomed heroic gesture of [Edward] Bast’s, and to force us to hear something truly beautiful through all the noise, incessant and insane, of the Discourse. […]

In fact the sorry truth is that [mass entertainments] may well be the best thing on offer, simply because the forces that produced them have absolutely bulldozed the last surviving hopes for art as a sphere of autonomous creation. But if that’s the case, well, then at least we have an archive of how things used to be, of postmodern novels from the late twentieth century, for example, which we are still free, for now, to go back and consult at our leisure, in order to remind ourselves how irreducibly complicated, and ultimately insaisissable, artists and intellectuals once knew the world to be.

The “gesture” he refers to in the first paragraph quoted is the great moment when Bast, a failed or anyway failing composer, tries to make JR, an 11-year-old idiot savant of finance, pause in his manic quest for cash to take just a few moments to listen to Bach’s haunting and glorious cantata Ich hatte viel Bekümmernis. Smith-Ruiu is right to call Bast’s desperate buttonholing of JR a mere gesture, because it’s hopeless, impossible … but perhaps all the more beautiful for that.

For a moment I thought that, in the sentence I’ve highlighted, Smith-Ruiu meant to use the word “abdicated,” but on reflection decided that “abnegated” is indeed the right word.

Claude Monet, The Thames below Westminster

David Hockey, from A Rake’s Progress (1963)

Claude Monet, The Museum at Le Havre

From the Wilton Diptych (National Gallery)

“The Teleprinter,” Eric Ravilious (1941)

Dear colleagues,

I must congratulate you all on what is, so far, a perfect execution of our Plan. You will recall that when we first met, more than a decade ago, we found ourselves confronted with a dramatic decline in enrollment in university humanities courses — throughout the Western world, but especially in the U.S.A. The self-declared radicals who dominated teaching in the humanistic disciplines seemed determined to alienate students as thoroughly as possible from literature, philosophy, and the arts; meanwhile, parents were frantically pushing their offspring towards courses in business and computer science. Very few young readers and thinkers could resist this double discouragement, especially since the forces doing the discouraging seemed in other respects to stand for opposing visions of what the world should be.

We quickly came to agreement on two points: first, that our chances of restoring the university humanities to their proper calling were so small that we could scarcely justify extending any efforts in that direction; and second, that in any case what matters in the long term is not the university disciplines but rather the cultural achievements that those disciplines once cared for: the novels and plays and poems, the treatises and dialogues, the sonatas and symphonies, the paintings and sculptures and beautifully designed buildings.

The key moment in our deliberations, as I recall, came when one of you reminded us of a (probably apocryphal) statement by the novelist Stendhal, who upon eating ice cream for the first time declared, “This is perfectly delicious. What a pity it isn’t forbidden.”

What a pity it isn’t forbidden. With that thought our Plan was born. The key, we realized, was to transform the works we love from objects of praise to objects of suspicion: things that required “trigger warnings” and deserved skeptical critique — perhaps utter denunciation for racism or homophobia or racism or ableism or … anything else we could think of.

Of course, we had to be careful — we had to work by suggestion and implication. We thought that if we made these accusations directly and explicitly we would be laughed at. Looking back, we can see that our caution was in one sense unnecessary: in this environment, no charge against great works of art could possibly be too outrageous. Still, our caution has served us well: We whispered the quiet part, and our colleagues eagerly said the quiet part out loud. Soon enough they were pronouncing their fatwas day in and day out.

What a pity it isn’t forbidden — the universal human desire for what we are told to hate and despise is our greatest ally. If we persist in our efforts, perhaps one day even Bach will be wholly excluded from concerts, even Shakespeare from theaters, even Homer and Dante from literature classes … and then the Renewal can at last begin.

Yours in the Great Cause,

Comrade Gamma

I began to learn that instrumentalists and singers often didn’t want or need … validation from the accompanist. Actually, most of the time, they preferred that you supply your steady support by staying clear of their path, not answering their every idea, but rather laying something down more locked into the bass and drums, even grid-like. If you are constantly trying to interact with every idea they present, you are not really accompanying, properly speaking — you are hijacking their ideas in a sense, and putting the focus on what you’re doing instead. It becomes more, “Look at me everyone, I’m so hip and adept at catching the soloist/singer’s ideas!” But what it’s really saying to the soloist/singer (and the audience) is: “Please like me!” It’s overbearing. It feels like one of those people you know who, when in a conversation with you, is constantly affirming what you’re saying — “Yeah … totally … exactly!” — before you’ve even finished your thought.

Mehldau started thinking back to his teenage years when he worked in a pizza joint in West Hartford, Connecticut:

I remembered the guy Jeremy at Papa Gino’s who was flipping pies within a few short months while I struggled at the grill. He didn’t give a shit — it was 5:45 evening rush hour, the place was packed and customers were eyeing him impatiently. But he was as cool as a cucumber, getting the pizzas in and out of the big oven. Maybe the thing was to just not give a shit with comping as well — not to throw away your taste and sensibility, mind you, but to bring a little of that cavalier pie-flipping thing into it. I started watching this less sensitive kind of comping going on at jam sessions or on gigs, and I didn’t always dig it. But I also noticed that other people often did — most importantly, the soloists they were comping behind. So what did it matter what I thought?

What a great analogy.

“Comping” is a universal term in jazz. It probably derives from “accompaniment,” maybe also from “complement,” but it has a distinctive valence: the good comper is the musician who can support the soloist in meaningful ways without becoming a rival for the audience’s attention. The best comper improves and strengthens the audience’s response to the soloist without anyone ever noticing.

Albert Murray, whom I’ve been thinking about a lot — see this post, and I’ll have an essay on him in the next issue of Comment, which I will no doubt call your attention to when it appears — used to say that his role was to comp for other artists: his friend Ralph Ellison (who was a music major in college and played the trumpet) was a great soloist, but Murray’s job was so support that kind of high-flying virtuosity with an imaginative but also reliable groove.

I love this idea of critical and essayistic writing as a kind of comping for the artists and thinkers I admire and learn from. I’d like to think that my best work exhibits some of the virtues of the quiet, cool, comping jazz pianist.

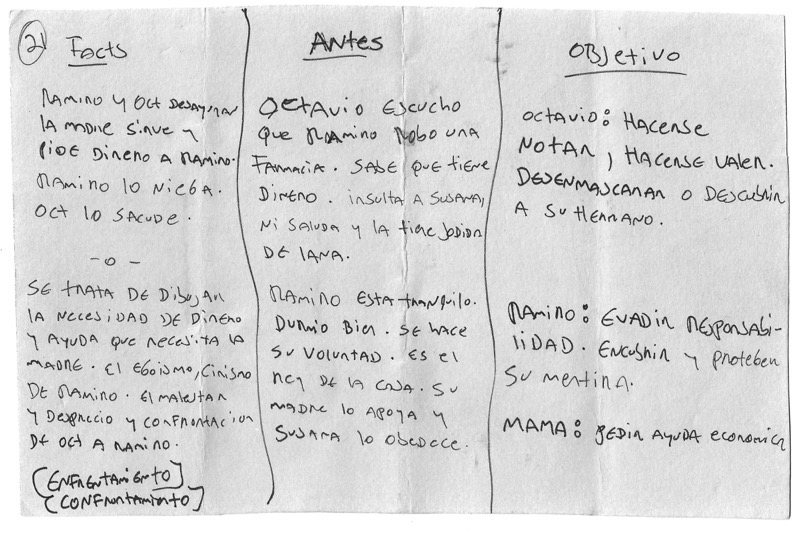

When preparing to shoot a scene, the film director Alejandro Iñárritu prepares note cards to help him organize his thoughts. ”During the production of a film, it’s easy to lose track of and forget the original intentions and motives that you had three years ago in your head and that are always so important.” Moreover, “As Stanley Kubrick once said, making a movie is like trying to write poetry while you’re riding a roller coaster. When one is shooting a film, it feels like a roller coaster, and it’s much more difficult to have the focus and mental space that one has during the writing or preparation of a film.”

So to forestall these problems, Iñárritu grabs a blank note card and divides it into columns, usually featuring six categories:

I love stuff like this – the improvisations, the invented methods and practices, what Matt Crawford calls the jigs, that any creative person must develop in order to manage the complexities of a serious project.

An anti-slavery medallion by Josiah Wedgwood

But:

Wedgwood seems to have thrown himself behind the cause of abolition out of genuine conviction. The medallion presented a marketing opportunity of sorts, but he manufactured it in large numbers at his own cost and ran the risk of alienating wealthy customers who opposed abolition. At the same time, as Hunt acknowledges, Wedgwood’s business was inextricable from the socioeconomic structures that sustained the slave trade. He depended on secure colonial shipping routes and sold extensively to the American colonies: Boston and Kingston were the perfect place to offload wares that had passed the peak of fashion back in Britain. Closer to home, many of his British customers derived their fortunes, one way or another, from colonial trade, including the trade in human beings. This trade helped to fuel the boom in domestic consumption that allowed Wedgwood to dream of selling high-quality artistic tableware to a growing middle-class market. Colonial commodities such as coffee, tea and sugar, with their accompanying social rituals, provided the raison d’être for many of Wedgwood’s most successful products.

I don’t know who Noah Kulwin is — someone, I don’t remember whom, linked to this post, which among other things talks about the assassination of JFK. If this sounds like I’m picking on poor Mr. Kulwin, my apologies; I really don’t mean to. I just want to illustrate a point.

In the post Kulwin quotes Don DeLillo’s comments on the Zapruder film. Here’s the key part:

The Zapruder film is a home movie that runs about eighteen seconds and could probably fuel college courses in a dozen subjects from history to physics. And every new generation of technical experts gets to take a crack at the Zapruder film. The film represents all the hopefulness we invest in technology. A new enhancement technique or a new computer analysis — not only of Zapruder but of other key footage and still photographs — will finally tell us precisely what happened.

For the rest of his post Kulwin speaks of “DeLillo’s faith in technology” and wants to argue with it. But of course — as anyone would know after reading even a smidgen of his fiction — DeLillo doesn’t have any faith in technology. Kulwin has misunderstood the last sentence of the quote above. He thinks DeLillo is making a claim, but in fact the novelist is narrating a perspective.

You can tell this is so by looking at the previous sentence, in which DeLillo speaks in broadly cultural terms of “all the hopefulness we invest in technology.” By “we” he doesn’t mean himself and his interviewer; he means Americans in general. And the sentence that follows — the one that Kulwin misunderstands — is not a statement of his own views, but a kind of expansion of or commentary on that hope. DeLillo is not saying that he believes that a new enhancement technique or a new computer analysis will finally tell us precisely what happened; he’s saying that the hope Americans invest in technology makes us — collectively, as a society — believe that a new enhancement technique or a new computer analysis will finally tell us precisely what happened.

As I’ve said many times before — e.g. here — I don’t think my students today are any worse than my students from years or even decades ago. But I believe that students today need more explanation of how writers think, how fictional narrative works. They have grown up in a media environment in which, as far as I can see, language is almost exclusively used for three purposes: to praise cultural friends, to condemn or mock cultural enemies, and to declare the Truth. The idea that language might be used to explore a way of seeing the world without judging that way — without issuing a 👍 or a 👎 — is pretty foreign to most of them, especially since most of the literature they’ve been assigned in school is either intrinsically didactic or is taught to them didactically.

This leads fairly regularly to misreadings of the type that Kulwin commits. Again, I know nothing about Kulwin, so I’m not trying to account for his error — only to note that it’s a very common kind of error these days. We live in a moment too polemical and defensive for undidactic art to flourish; most people, it seems, suspect any artwork that doesn’t declare its principles unambiguously.

Some years ago Mandy Patinkin described the lunch meeting at which Rob Reiner recruited him to play in The Princess Bride. He recalled that

He said to me, ‘The way I want everybody to play this is as though you have a hand of cards, and I want all of us to almost show the hand to the audience, but we never really show it. That’s how I want it to happen.’ So, he collected a bunch of people who would play cards that way.

I think that’s actually a pretty good explanation for why The Princess Bride is such a brilliant movie, but whether it is or not, it’s a great way to describe what the greatest stories always do. You get a peek at the cards maybe, but not enough to be sure about the whole hand. You have to guess; you have to think; you have to ask difficult questions like “How might I behave if I had a great hand? A lousy one?” You have to imagine. All the great artists and writers do.

The Struggle With The Audience:

By 2020, [Sam] Carter was a battle-hardened veteran of the music scene. He’d been making records with this group for twelve years, and Architects had had enough success not to worry too much about negative reactions to new material. It was also quickly apparent that Creatures was going to be a big hit. Despite all this, he found the reaction to hard to deal with: “It was doing huge numbers on the streaming services, but all I could see were these horrible comments.” On YouTube and Instagram, the negative reactions become increasingly extreme as people competed to make the most negative comment. “It’s hard, when you’ve put your heart and soul into something, and someone says, ‘I’m never listening to your band again, you’ve ruined it’.”

Carter then makes a striking assertion. If social media had come along earlier, he says, “Sergeant Pepper wouldn’t exist. The most important records of our time wouldn’t exist.”

This whole essay by Ian Leslie is great, and a useful counterpart to my post the other day about the challenges of chasing eyeballs.

However, there’s another side to the story of artists and their audiences. My buddy Austin Kleon wrote last week,

One reason I feel so lucky to be an independent writer with a great audience: I don’t answer to any shareholders but readers. I don’t have to grow my business if I don’t want to. I can do my thing the way I want to do it for the people who want it. And I can do it the way I want to do it.

I think Austin has this attitude because he has never tried to get famous, to go viral, all that crap; he has tried (a) to do good, honest, useful, helpful work that (b) supports his family. Turns out there’s an audience for that! And Austin can call his audience “great” because he has set a tone — a tone of generosity, kindness, thoughtfulness — and they’ve picked up on that. So maybe the lessons here are:

See also: this blog’s mission statement.

Here’s a little offshoot of my work on Auden’s The Shield of Achilles.

This painting by Piero di Cosimo — see a larger version here — is called The Finding of Vulcan on the Island of Lemnos, but it wasn’t always called that. For a long time it was thought to represent the story of Hylas, the beautiful warrior and companion of Heracles who was abducted by nymphs. But, the great art historian Erwin Panofsky pointed out in his 1939 book Studies in Iconology, the image doesn’t really fit the story. Compare Piero’s painting with that of John William Waterhouse and you’ll see the difference: Waterhouse’s nymphs are clearly drawing Hylas into the water, in accordance with the myth, but Piero’s nymphs are doing something different: they’re helping a fallen youth get up from the ground. (Or, rather, one of them is: the others are looking on with curiosity, amusement, or concern, and talking about this odd stranger.)

What’s going on here? To answer you have to go back to Homer: Iliad, Book I. There Hephaestus speaks to his mother Hera:

You remember the last time I rushed to your defense?

[Zeus] seized my foot, he hurled me off the tremendous threshold

and all day long I dropped, I was dead weight and then,

when the sun went down, down I plunged on Lemnos,

little breath left in me. But the mortals there

soon nursed a fallen immortal back to life.

But “the mortals there” is not what Homer wrote; instead he wrote Σίντιες ἄνδρες, the “Sintian men.” The problem for later scholars is that nobody knows who the Sintian men were. Servius, a Latin grammarian and contemporary of Augustine of Hippo, wrote a learned commentary on Vergil in which he drew on that passage from Homer: Vulcano contigit, qui cum deformis esset et Iuno ei minime arrisisset, ab Iove est praecipitatus in insulam Lemnum. illic nutritus a Sintiis…. “Vulcan, because he was deformed and Juno did not smile on him, was hurled by Jove onto the island of Lemnos. There he was nurtured by the Sintii.”

This caused great confusion for scholars in the Renaissance for whom the word Sintii was meaningless. They therefore assumed, as learned philologists of that era were wont to assume, that some scribal error had occurred. Instead of nutritus a Sintiis Servius’s original text surely was nutritus absintiis, nurtured on wormwood. No, said others, it was nutritus ab simiis: He was nurtured by apes — and thus, we might say, a type of Tarzan. (Lord Greystoke, meet your ancestor Vulcan.) Boccaccio, in his enormously influential Genealogy of the Pagan Gods, accepted the Simian Hypothesis, and so evidence of it turns up in, for instance, an allegorical fresco, possibly by Cosmè Aura, in the Palazzo Schifanoia in Ferrara:

See in the upper-left corner Vulcan’s forge, and, nearby, the apes pulling some kind of elaborate palanquin?

But there was a third opinion — philologically the least convincing, surely, but artistically the most appealing: Servius’s text read nutritus ab nimphis — nurtured by nymphs. And that, Panofsky convincingly argued, is the reading Piero adopted. Those nymphs aren’t drawing Hylas into the water — there is no water — they’ve come running when they heard a big thump, or perhaps saw “Something amazing, a boy falling out of the sky,” and now they’re chattering away about this remarkable event as one of them helps the stunned but unharmed god to his feet. Poor little fellow. (He looks about two-thirds their size.) Some of the nymphs seem to find the whole thing funny, but in the end they’ll take good care of him.

UPDATE: I’ve been corresponding with Adam Roberts about this and we’ve both been searching for the mysterious Sintians. The wonderful Sententiae Antiquae blog quotes from the Homeric scholia:

“[The Sintian men}: Philokhoros says that because they were Pelasgians they were called this because after they sailed to Brauron they kidnapped the women who were carrying baskets. For they call “harming” [to blaptein] sinesthai.

But Eratosthenes says that they have this name because they are wizards who discovered deadly drugs. Porphyry says that they were the first people to make weapons, the things which bring harm to men. Or, because they were the first to discover piracy.

This story of a god being raised by PIRATE WIZARDS sounds like the best idea for a fantasy novel I have ever heard.

Don’t Fear the Artwork of the Future – The Atlantic:

What is so tiresome about the fear of AI art is that all of this has been said before—about photography. It took decades for photography to be recognized as an art form. Charles Baudelaire famously called photography the “mortal enemy” of art. The Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which was among the first American institutions to collect photographs, didn’t start doing so until 1924. The anxiety around the camera was nearly identical to our current fear of creative AI: Photography wasn’t art, but it was also going to replace art. It was “mere mechanism,” as one critic put it in 1865. I mean, it’s not art if you’re just pushing some buttons, right?

This is one of the laziest tropes of pseudo-thinking, but also one of the most common. If you want to try it for yourself, follow these steps:

Indubitable! (Just make sure you don’t notice any situations in the past in which the people who were afraid were right. Nobody says, “Those who worry about appeasing Putin should remember that in the late 1930s a bunch of nervous Nellies worried about appeasing Hitler too.”)

But often there’s another element of dumbness to this kind of take: not just the inability to reason sequentially, but the ignoring of inconvenient facts. For while photography didn’t “replace art,” it largely did replace certain kinds of art, and radically changed the cultural place of drawing and painting.

For my part, I think some of these changes were good and some were not so good. When it became clear that to most people photographs looked more “real,” more precisely representational, than paintings, painters began exploring various alternatives to straightforward representation: first Impressionism, pointillism, and later on completely non-representational painting. (Nowadays “photorealistic painting” is merely a joke or meta-artistic game, as in the works of Chuck Close.) I think these were exciting and vital developments, and I wouldn’t want to see them undone. But, that said, when I think about how Picasso could draw at the age of eleven —

— I do find myself wondering how he might have developed as an artist if he had been working in the days before photography. If much was gained when Picasso was liberated from straightforwardly representational art, we can’t know what was lost. But we lost something.

The rise of photography had a broader cultural consequence too. Before photography became commonplace, an ability to draw was almost a requirement for travelers. People needed to be able to make competent sketches of the exotic places they visited, because otherwise how would they be able to remember everything, or properly describe it to others? A world in which Ruskin had simply taken photographs in Venice rather than draw its monuments would be a diminished world.

So, did photography kill art? By no means. Did it change it radically? It certainly did. And were all those changes positive ones? Nope.

In a famous letter, John Adams wrote from Paris to his beloved Abigail:

To take a Walk in the Gardens of the Palace of the Tuilleries, and describe the Statues there, all in marble, in which the ancient Divinities and Heroes are represented with exquisite Art, would be a very pleasant Amusement, and instructive Entertainment, improving in History, Mythology, Poetry, as well as in Statuary. Another Walk in the Gardens of Versailles, would be usefull and agreable. But to observe these Objects with Taste and describe them so as to be understood, would require more time and thought than I can possibly Spare. It is not indeed the fine Arts, which our Country requires. The Usefull, the mechanic Arts, are those which We have occasion for in a young Country, as yet simple and not far advanced in Luxury, altho perhaps much too far for her Age and Character.

I could fill Volumes with Descriptions of Temples and Palaces, Paintings, Sculptures, Tapestry, Porcelaine, &c. &c. &c. — if I could have time. But I could not do this without neglecting my duty. The Science of Government it is my Duty to study, more than all other Studies & Sciences: the Art of Legislation and Administration and Negotiation, ought to take Place, indeed to exclude in a manner all other Arts. I must study Politicks and War that my sons may have liberty to study Painting and Poetry Mathematicks and Philosophy. My sons ought to study Mathematicks and Philosophy, Geography, natural History, Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture, in order to give their Children a right to study Painting, Poetry, Musick, Architecture, Statuary, Tapestry and Porcelaine.

Only the last two sentences of the letter are typically quoted, but I think it’s useful to see the larger context, especially Adams’s regret at the matters of great interest to him that he doesn’t fully understand and simply cannot take the time to understand. He had recently been engaged in complicated and tense negotiations with the French foreign minister, the Comte de Vergennes, which around this time resulted in the Frenchman declaring that he wouldn’t deal with Adams any more but only with the less astringent Benjamin Franklin. (Perhaps Adams should have been working harder at the study of the Art of Negotiation.)

It’s interesting to note the change of mind he undergoes between the penultimate and final sentence: in the former he thinks his sons may well study Painting and Poetry, but then he reconsiders and thinks, well, perhaps it would be better for them to pursue “Naval Architecture, navigation, Commerce and Agriculture” and the like so that their sons can study Painting and Poetry. His was, after all, “a young Country, as yet simple and not far advanced in Luxury” — and not likely to be much further advanced in a single generation.

Well, right now we seem to be regressing towards Adams’s state of affairs. Everyone in power, or aspiring to power, in this country seems to be studying Politics and War, though they will sometimes cover that study with a flimsy disguise.

On the so-called Left we see surveillance moralism (and often enough the sexualization of children and early teens) masquerading as science.

On the so-called Right? It’s wrathful trolling masquerading as political philosophy.

None of these folks, God bless their earnest if shriveled hearts, have any room inside for the arts. Everything has to serve their political purposes, and works of art are rarely sufficiently blunt instruments. Thus Michael Lind writes — in an otherwise useful essay — that the goal of the public intellectual is to “influence voters,” because what other reason could an intellectual possibly have for writing? (Michael Lind is a very intelligent and often illuminating writer, but he really does seem to think that nothing exists in the human world except electoral politics.) The one arguably-artistic preference these would-be elites of Left and Right share is a liking for Game of Thrones (and now House of the Dragon) but only because that world is a wish-fulfillment dream for aspiring tyrants.

Well, here at the Homebound Symphony I’ll be focusing on the arts more and more, and if sometimes connecting their wisdom to the social and political concerns that trouble our minds and dreams, I’ll try never to do it in a way that blunts those sharp instruments that pierce soul and spirit. And I’ll do this in honor of John Adams, so that his sacrifice was not in vain.

(I also think there are every good reasons for Christians to be especially attentive to the arts — even those Christians who don’t think of themselves as arty. That may be a topic for future posts, because my reasons for so thinking are not common ones.)

But I can do all this because of others who are doing some necessary but ugly work. The internet’s own John Adamses … sort of. I’ll write a follow-up post on some of these helpful people.

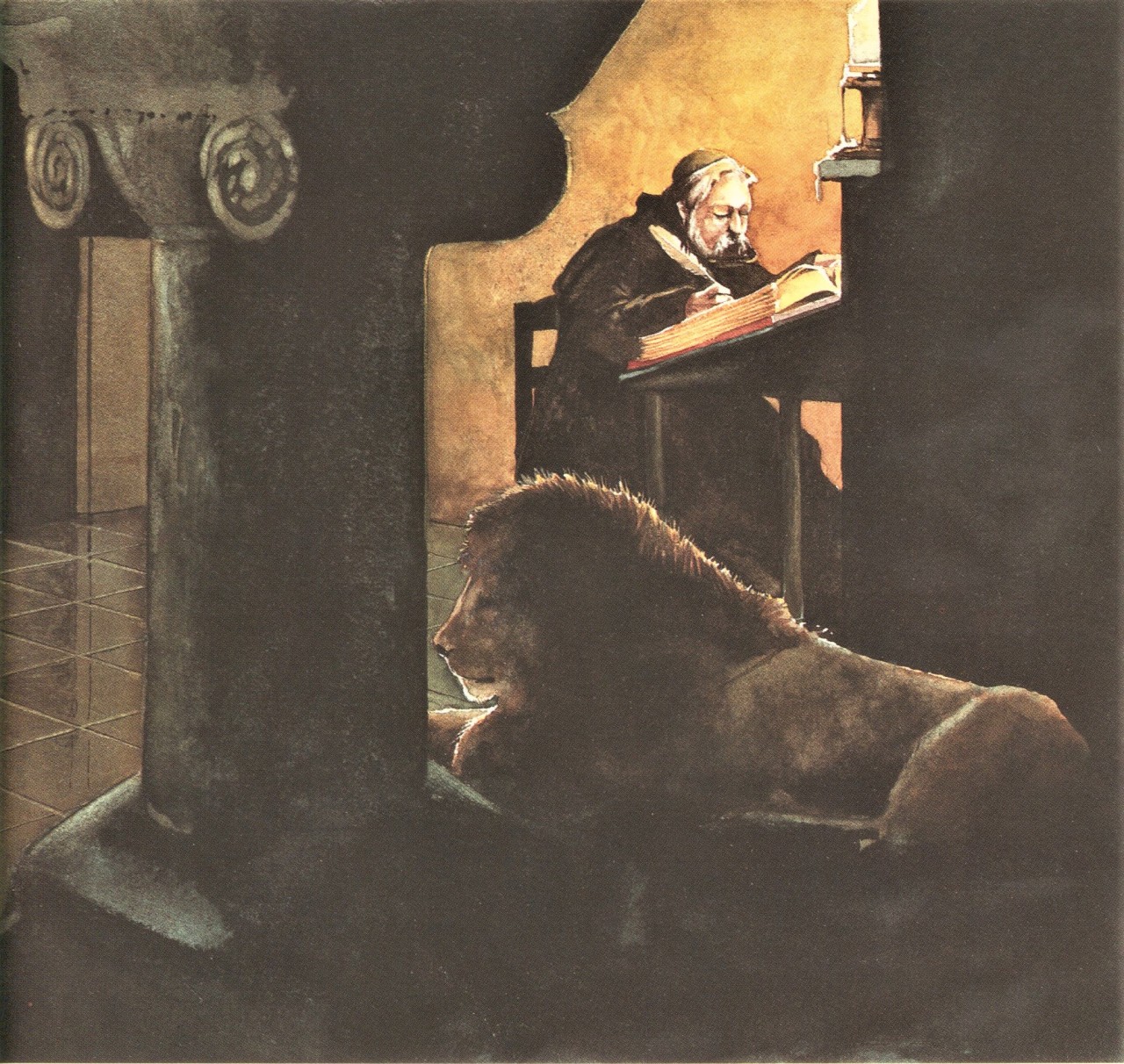

Barry Moser, St. Jerome and the Lion

How Moral Panic Has Debased Art Criticism – Alice Gribbin:

Artwords are not to be experienced but to be understood: From all directions, across the visual art world’s many arenas, the relationship between art and the viewer has come to be framed in this way. An artwork communicates a message, and comprehending that message is the work of its audience. Paintings are their images; physically encountering an original is nice, yes, but it’s not as if any essence resides there. Even a verbal description of a painting provides enough information for its message to be clear.

This vulgar and impoverishing approach to art denigrates the human mind, spirit, and senses. From where did the approach originate, and how did it come to such prominence? Historians a century from now will know better than we do. What can be stated with some certainty is the debasement is nearly complete: The institutions tasked with the promotion and preservation of art have determined that the artwork is a message-delivery system. More important than tracing the origins of this soul-denying formula is to refuse it — to insist on experiences that elevate aesthetics and thereby affirm both life and art.

I wonder if this move is driven, in large part, by the demands of the ancient warfare between art and criticism: the critical defining of art as a message-delivery system is a way of saying that art merely does what criticism does, just not as well. For critics are habitually in the message-delivery business.

There’s a self-regarding preciousness to much of Donald Judd’s work — and to the whole town of Marfa — that I don’t care for, but he also did some truly major work and I hope the Chinati Foundation reaches its financial goals. The most interesting installation there, I think, is Robert Irwin’s massive study in light and shade.

Pop Culture Has Become an Oligopoly – by Adam Mastroianni:

In every corner of pop culture — movies, TV, music, books, and video games — a smaller and smaller cartel of superstars is claiming a larger and larger share of the market. What used to be winners-take-some has grown into winners-take-most and is now verging on winners-take-all. The (very silly) word for this oligopoly, like a monopoly but with a few players instead of just one.

Remember when we were looking forward to the era of the Long Tail? Nah, that didn’t happen. At least not in the way predicted. We do, praise God, have unprecedented access to art, books, music, movies — but we often get to choose between the colorless tasteless mega-productions of the oligopoly or very small things made at the cultural and economic margins.

This works out differently in different art forms, and I want to think more about the details. But it does seem to me that there’s a kind of squeezing-out of the middle. The midlist author is disappearing — heck, in another time and place I might well have been a midlist author, but I could never sell enough books in the current environment to make a living. Also, it seems that only a few bands — good old-fashioned guitar/keyboards/bass/drum bands — can afford to tour any more, and most of those are comprised of people over sixty. Younger musicians tend to work solo or duo, or form short-term collaborations, and thick musical textures tend to be developed (when they’re developed all) through digital instrumentation rather than through people learning how to play together. The new economics of art has been hard on all musical genres, but especially, I think, on jazz. Which was struggling anyway.

Obviously you can’t generalize too grossly here; the situation in the visual arts is rather different. But in many art forms, it seems to me, we have the massive-in-scale and massive-in-popularity and small-in-scale and small-in-popularity — and not much in between.

My friend Chad Holley — lawyer, teacher, writer — describing a bold pedagogical decision:

If it was sage to leave well enough alone, I slipped up last month adding Solzhenitsyn’s lecture to the syllabus of a Law and Literature course I’m teaching at a local law school. Surely now I needed some intelligible comment on it, some ready defense. At least one faculty member, after all, had pushed back against the course on grounds of, well, frivolity. Fortunately, the dean who hired me had a delightfully simple view: the course would make students better people, and better people would make better lawyers. It carried the day, who am I to quibble? But for the Solzhenitsyn piece I was on my own. In the end I muttered to myself something about it offering an aesthetic that relates literature to morality, politics, and even the global order without succumbing to the instrumentalism of the savage. Eh. Close enough for adjunct work.

But did I say I added the piece to the syllabus? Friend, I began the course with it. We introduced ourselves, shared reasons for being here, covered some ground rules. Then I said, as distracted as I sounded, “Allll righty …so …” I had not anticipated just how much respect, how much admiration, I would feel for this small, diverse, self-selected group. They had read War and Peace “twice, but in Spanish,” their families had fled Armenia to escape Stalin, they were raising children, running businesses, staffing offices, nearly every one of them holding down a full-time day job while attending law school in the evenings, on the weekends. Had I really required these serious, ass-busting, tuition-remitting people to read an essay suggesting — I could barely bring myself to mouth it — beauty will save the world? What was I going to say for this in the face of their withering skepticism, their yawn of silence?

Read on to find out.

Brain Sciences | Is Reduced Visual Processing the Price of Language?:

Abstract

We suggest a later timeline for full language capabilities in Homo sapiens, placing the emergence of language over 200,000 years after the emergence of our species. The late Paleolithic period saw several significant changes. Homo sapiens became more gracile and gradually lost significant brain volumes. Detailed realistic cave paintings disappeared completely, and iconic/symbolic ones appeared at other sites. This may indicate a shift in perceptual abilities, away from an accurate perception of the present…. Studies show that artistic abilities may improve when language-related brain areas are damaged or temporarily knocked out. Language relies on many pre-existing non-linguistic functions. We suggest that an overwhelming flow of perceptual information, vision, in particular, was an obstacle to language, as is sometimes implied in autism with relative language impairment. We systematically review the recent research literature investigating the relationship between language and perception. We see homologues of language-relevant brain functions predating language. Recent findings show brain lateralization for communicative gestures in other primates without language, supporting the idea that a language-ready brain may be overwhelmed by raw perception, thus blocking overt language from evolving. We find support in converging evidence for a change in neural organization away from raw perception, thus pushing the emergence of language closer in time. A recent origin of language makes it possible to investigate the genetic origins of language.