There’s a really extraordinary moment in George Eliot’s The Mill on the Floss, a moment that says something profound about what we might call the ecology of reading in the age of print.

First, some background: Mr. Tulliver – the father of Tom and Maggie Tulliver, the two central characters in this novel – embarks upon a rash lawsuit which fails, and its failure sends him into bankruptcy. His family lose almost everything. As they are trying to adjust to their economic and social fall, Tom Tulliver receives a visit from his childhood friend Bob Jakin. Bob is a packman, a kind of traveling salesman who goes about on foot bearing a pack full of random goods which he sells mainly to the working poor. Bob is little better than working poor himself, even if through diligence and shrewd bargaining he is rising in the world: certainly he is constantly aware of his social inferiority to the Tullivers, despite their distressed circumstances; he always refers to Tom as “Master Tom.” Bob visits to try to give the Tullivers some money which Tom’s pride will not allow him to receive (probably he wouldn’t receive it from anybody, but he certainly won’t receive it from Bob). During their visit Tom’s younger sister Maggie comes in to the parlor and discovers that in the recent auction of their goods her books had been sold. Her eyes fill with tears; she is especially grieved over the loss of the family copy of The Pilgrim’s Progress: “I thought we should never part with that while we lived.”

Maggie is a devoted reader, much more so than her brother, and earlier in the book, when Maggie visits Tom at the pastor’s house where he is a paying pupil, we see that her intellectual interests are far stronger than his own and her capabilities far greater. But this was not an era in which young women of such gifts were reliably provided with an education adequate to them, so Maggie must remain largely self-educated. Thus she treasures so greatly the handful of books she owns and is so grieved at their disappearance.

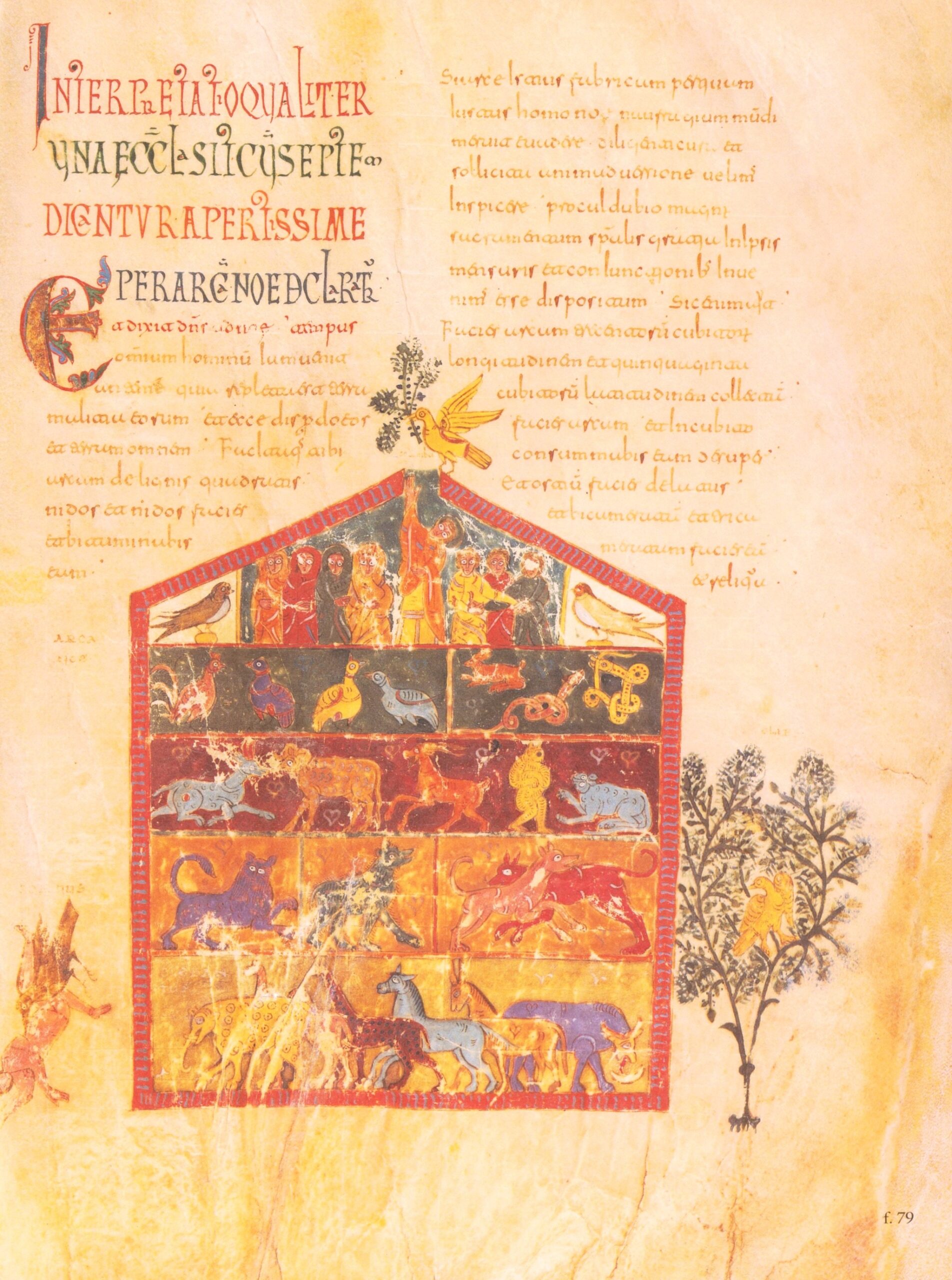

Bob, who adores Maggie, though as a creature far above him in the Great Chain of Being, notices her distress and some weeks later pays her another visit. He has brought with him some books that he has scavenged in the course of his labors. Some of them are illustrated books – Bob himself thinks the illustrations quite fine and likely to interest Maggie – but he’s also aware that Maggie likes books with words in them and so makes sure to bring her a parcel of those: “I thought you might like a bit more print as well as the picturs, an’ I got these for a sayso, – they’re cram-full o’ print, an’ I thought they’d do no harm comin’ along wi’ these bettermost books.” (Bob, being illiterate, can’t tell you anything about the content of the books, he can only judge quantity of print.) Maggie receives these gifts gratefully but sets them aside; she has much on her mind and it’s not until later that she thinks to take up one of the volumes.

She does so at a time of great personal and familial distress. She has been forced to leave school — where she had been learning at least a few rudimentary skills that a young woman might need — in order to tend to her father, who has collapsed in the aftermath of his financial defeat and its consequent shame. All her life now is caring for her father’s needs, but she is a teenage girl of high intellect and great passion, and the consumption of her whole being in the dreary round of daily service is of course a struggle to her. Among the books in Bob’s parcel, the one that catches her eye is an old translation of Thomas a Kempis’s The Imitation of Christ. She feels that she has heard the name but knows nothing about the book; she picks it up and begins to read.

And here is where something extraordinary happens.

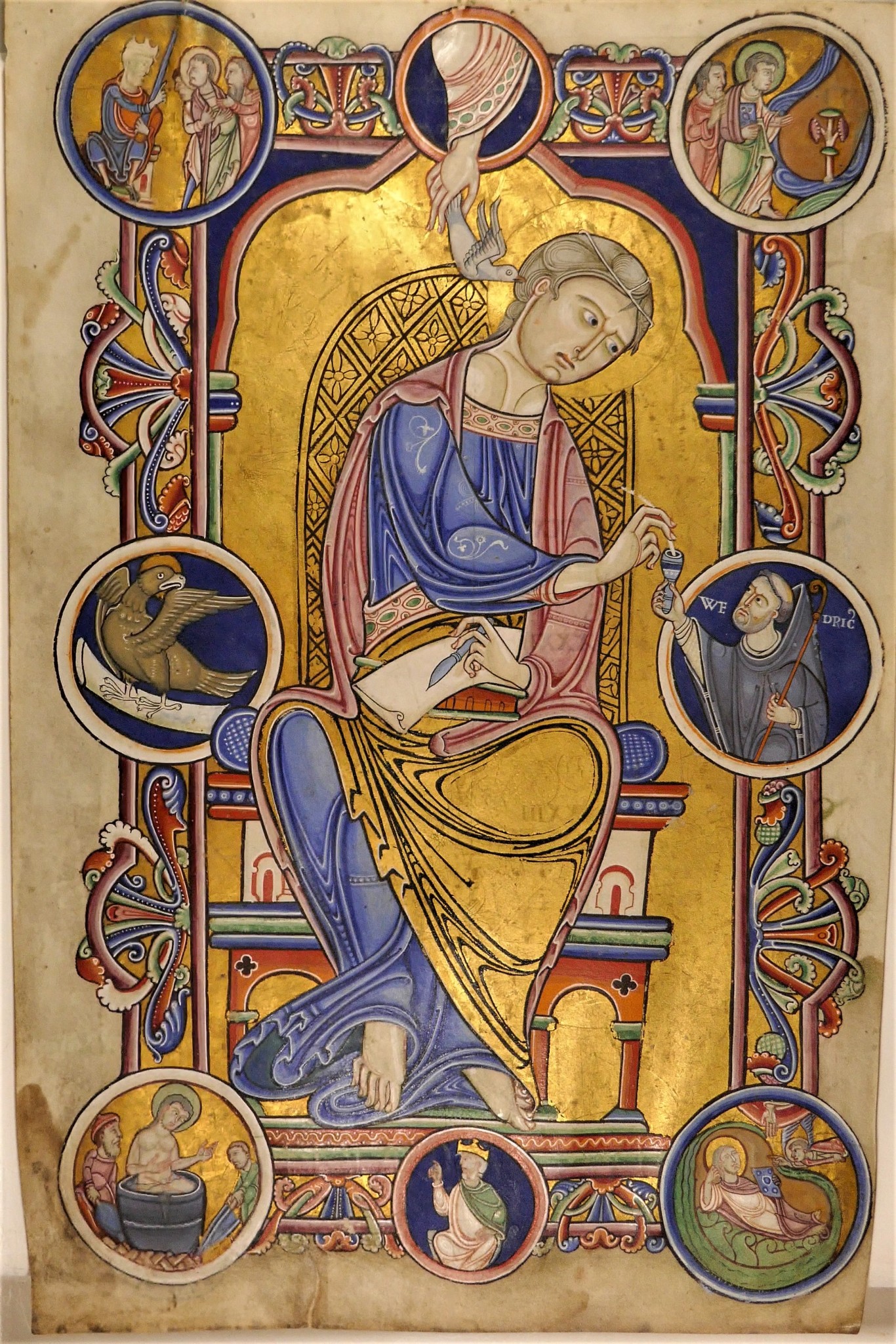

She took up the little, old, clumsy book with some curiosity; it had the corners turned down in many places, and some hand, now forever quiet, had made at certain passages strong pen-and-ink marks, long since browned by time. Maggie turned from leaf to leaf, and read where the quiet hand pointed: “Know that the love of thyself doth hurt thee more than anything in the world…. If thou seekest this or that, and wouldst be here or there to enjoy thy own will and pleasure, thou shalt never be quiet nor free from care; for in everything somewhat will be wanting, and in every place there will be some that will cross thee…. Both above and below, which way soever thou dost turn thee, everywhere thou shalt find the Cross; and everywhere of necessity thou must have patience, if thou wilt have inward peace, and enjoy an everlasting crown…. If thou desirest to mount unto this height, thou must set out courageously, and lay the axe to the root, that thou mayest pluck up and destroy that hidden inordinate inclination to thyself, and unto all private and earthly good. On this sin, that a man inordinately loveth himself, almost all dependeth, whatsoever is thoroughly to be overcome; which evil being once overcome and subdued, there will presently ensue great peace and tranquillity…. It is but little thou sufferest in comparison of them that have suffered so much, were so strongly tempted, so grievously afflicted, so many ways tried and exercised. Thou oughtest therefore to call to mind the more heavy sufferings of others, that thou mayest the easier bear thy little adversities. And if they seem not little unto thee, beware lest thy impatience be the cause thereof…. Blessed are those ears that receive the whispers of the divine voice, and listen not to the whisperings of the world. Blessed are those ears which hearken not unto the voice which soundeth outwardly, but unto the Truth, which teacheth inwardly.”

The quiet hand – Eliot repeats the phrase: “She went on from one brown mark to another, where the quiet hand seemed to point, hardly conscious that she was reading, seeming rather to listen.” Her reading of this book becomes a kind of three-way conversation: this miserable adolescent girl in Lincolnshire, the old monk, and the long-dead reader whom Maggie thinks of as her “invisible teacher.”

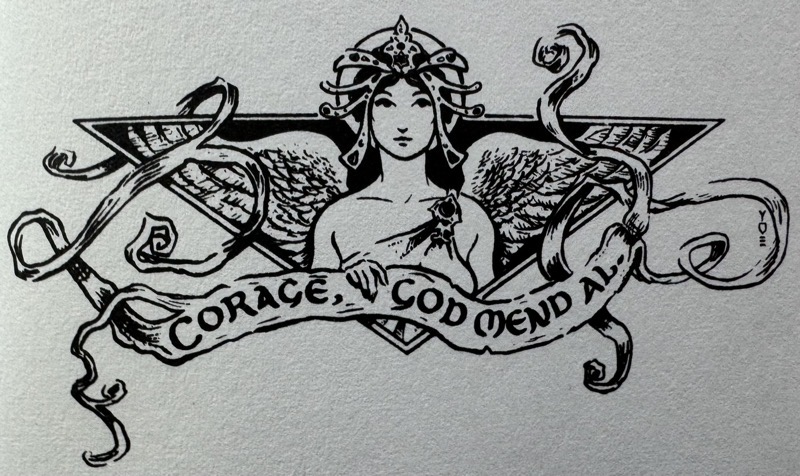

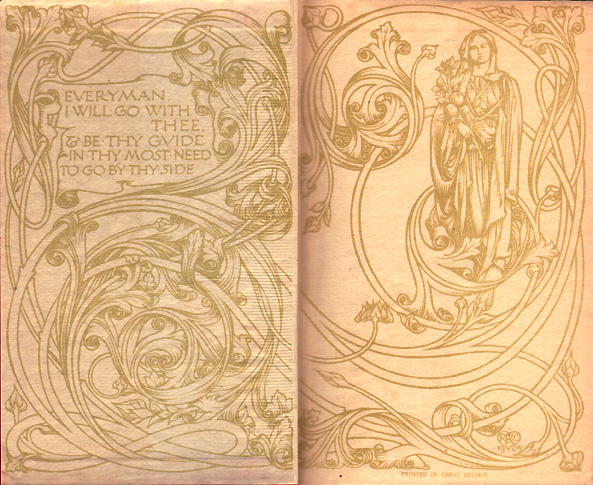

Maggie has been deprived of visible teachers, at least ones who would teach her the things that she most cares about, but here she finds one – in the margins of an old book picked up in some dingy provincial shop by an illiterate packman – who is able to guide her in her time of greatest distress. I find myself remembering here the motto of the Everyman’s Library editions, words that in the medieval morality play Everyman are spoken by Knowledge:

Everyman,

I will go with thee,

and be thy guide,

In thy most need

to go by thy side.

So the publisher, by gathering these great books together and making them both presentable and affordable, can become itself an “invisible teacher.”

By the time she wrote The Mill on the Floss, Eliot had (to my regret) left behind the evangelical piety that dominated her own teenage years; but that does not reduce her admiration of The Imitation of Christ:

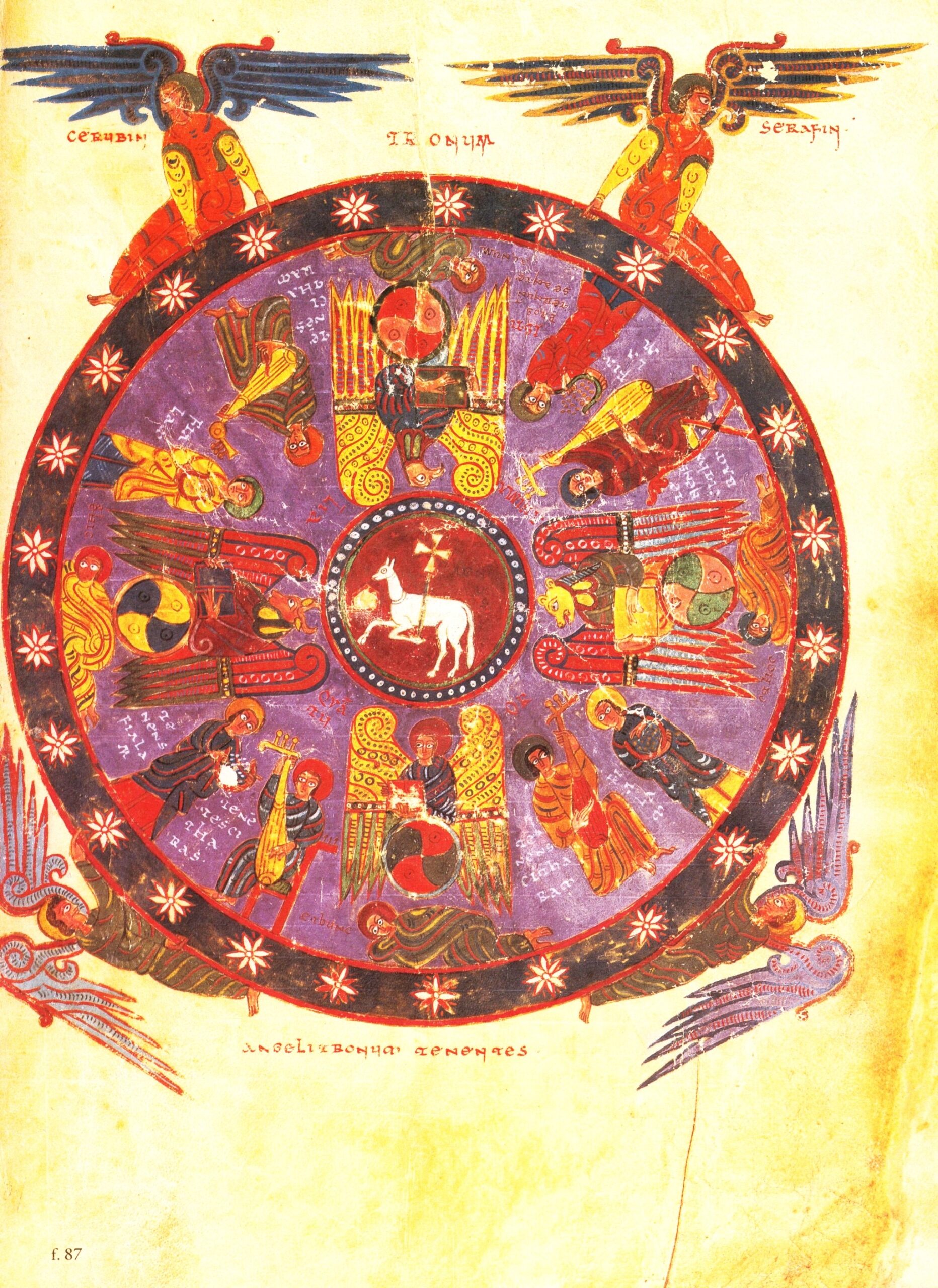

I suppose that is the reason why the small old-fashioned book, for which you need only pay sixpence at a book-stall, works miracles to this day, turning bitter waters into sweetness; while expensive sermons and treatises, newly issued, leave all things as they were before. It was written down by a hand that waited for the heart’s prompting; it is the chronicle of a solitary, hidden anguish, struggle, trust, and triumph, not written on velvet cushions to teach endurance to those who are treading with bleeding feet on the stones. And so it remains to all time a lasting record of human needs and human consolations; the voice of a brother who, ages ago, felt and suffered and renounced, – in the cloister, perhaps, with serge gown and tonsured head, with much chanting and long fasts, and with a fashion of speech different from ours, – but under the same silent far-off heavens, and with the same passionate desires, the same strivings, the same failures, the same weariness.

That heartfelt and heart-prompted book was once found by a reader whose own heart responded to it; and he (or she) recorded that response with a pen; and that record, many years later, gave direction and comfort to a friendless and miserable girl in a small English town.

This idea of books and their readers as friends and teachers, as a silent fellowship extending across time and space, is a very dear one to me. Like Francis Spufford, I was a child that books built; in a childhood with its own deep unhappiness, books were my best companions and almost my only real teachers. And at a moment when our educational system is in such disarray, when it so often does ill rather than good to its students, it’s important to remember that these resources are available – and available in radically more extensive forms than Maggie Tulliver could have dreamed possible. The world of print, publication, and distribution holds together an ecology of reading, a vast circulatory system by which mind speaks to distant mind, and heart to distant heart.

That old copy of The Imitation of Christ and the invisible teacher within it guide Maggie through a great crisis in her life. Through them she learns the discipline of self-renunciation, and while she later comes to question – is forced by a man who loves her to question – whether self-renunciation is indeed her call, there is no question that what she learned from that book truly saves her in that crisis. And she never wholly forgets what she learned in that season of life, through the book’s text and through the patient directions of the quiet hand.

The lessons of the old monk and the invisible teacher might have been valuable to her much later in life, had she been granted a long life. But that is a longer and a darker story, one that I will take up elsewhere.