All forms of privilege — including the ones I benefit from — are morally dangerous, but I think the form of privilege that does the greatest social and political damage is that of never having to live among or even talk to people who disagree with you about the Good.

Tag: ethics (page 2 of 4)

I have had with my friend Wes Jackson a number of useful conversations about the necessity of getting out of movements — even movements that have seemed necessary and dear to us — when they have lapsed into self-righteousness and self-betrayal, as movements seem almost invariably to do. People in movements too readily learn to deny to others the rights and privileges they demand for themselves. They too easily become unable to mean their own language, as when a “peace movement” becomes violent. They often become too specialized, as if finally they cannot help taking refuge in the pinhole vision of the institutional intellectuals. They almost always fail to be radical enough, dealing finally in effects rather than causes. Or they deal with single issues or single solutions, as if to assure themselves that they will not be radical enough.

And so I must declare my dissatisfaction with movements to promote soil conservation or clean water or clean air or wilderness preservation or sustainable agriculture or community health or the welfare of children. Worthy as these and other goals may be, they cannot be achieved alone. They cannot be responsibly advocated alone. I am dissatisfied with such efforts because they are too specialized, they are not comprehensive enough, they are not radical enough, they virtually predict their own failure by implying that we can remedy or control effects while leaving causes in place. Ultimately, I think, they are insincere; they propose that the trouble is caused by other people; they would like to change policy but not behavior.

A vital reminder from Berry that all of us who want to recommend significant social change need to think economically and ecologically.

Breaking Bad is a story about ressentiment; about a man who feels himself marginalized and neglected, powerless and ineffectual, who, therefore, cannot resist the temptation to establish himself as a Power — as a man who says, and means it: “I am the one who knocks.”

Better Call Saul dramatizes a radically different form of human frailty: the temptation of the con. The person so tempted may be socially marginal or socially dominant or something in between — though the marginal will have a few more incentives pushing them towards scamming. What’s at work here is not ressentiment but rather (a) a desire to dominate people, a desire to know what they don’t know and act on that knowledge in a way that enables you to triumph over them, and (a) the intellectual challenge of building a successful scam: the meticulous planning, the anticipation of the responses of your marks, the ability to improvise when things go wrong. What you see in Better Call Saul is, first, how the power of these two motives — the desire to dominate and the love of intellectual challenge — vary from person to person, and within a person from moment to moment; and also the crack-like addictiveness that follows upon the running of a successful scam.

Both shows then are about extremes of human frailty — frailty become perversity, perversity become wickedness — and how inescapable the associated habits of thought and action can be.

My friend Chad Holley — lawyer, teacher, writer — describing a bold pedagogical decision:

If it was sage to leave well enough alone, I slipped up last month adding Solzhenitsyn’s lecture to the syllabus of a Law and Literature course I’m teaching at a local law school. Surely now I needed some intelligible comment on it, some ready defense. At least one faculty member, after all, had pushed back against the course on grounds of, well, frivolity. Fortunately, the dean who hired me had a delightfully simple view: the course would make students better people, and better people would make better lawyers. It carried the day, who am I to quibble? But for the Solzhenitsyn piece I was on my own. In the end I muttered to myself something about it offering an aesthetic that relates literature to morality, politics, and even the global order without succumbing to the instrumentalism of the savage. Eh. Close enough for adjunct work.

But did I say I added the piece to the syllabus? Friend, I began the course with it. We introduced ourselves, shared reasons for being here, covered some ground rules. Then I said, as distracted as I sounded, “Allll righty …so …” I had not anticipated just how much respect, how much admiration, I would feel for this small, diverse, self-selected group. They had read War and Peace “twice, but in Spanish,” their families had fled Armenia to escape Stalin, they were raising children, running businesses, staffing offices, nearly every one of them holding down a full-time day job while attending law school in the evenings, on the weekends. Had I really required these serious, ass-busting, tuition-remitting people to read an essay suggesting — I could barely bring myself to mouth it — beauty will save the world? What was I going to say for this in the face of their withering skepticism, their yawn of silence?

Read on to find out.

I have come to believe that almost all of our social pathologies stem from two deeply-ingrained tendencies:

- People care more about belonging to the Inner Ring than about telling the truth. Indeed, in many cases lying for the Ingroup is the best means of demonstrating one’s commitment to it.

- People are presentists not just in the sense I often talk about — attending only to the stimuli the dominant media offer now — but in the sense of doing whatever offers immediate gratification and leaving the future to care for itself.

Anyone who cares about the flourishing of our social order and of the planet needs to think about how to chip away at these tendencies — and I think “chipping away” is the best we can do. A while back I was on a Zoom call with Jonathan Haidt, and I asked him whether he thought that seeing and acknowledging the truth about one’s condition might be an evolutionarily adaptive trait. He replied that beyond some fairly low-level lizard-brain things — like seeing that that really is a bear charging at you and you had therefore better take evasive action — he thought not. For human beings, the ability to belong is more adaptive than the ability to see what’s true.

So: these are incredibly powerful forces; none of us will ever be completely free from them, and some of us will be prisoners of them all our lives long; but their hold can be weakened, and I think constantly about how to do that — for myself first, and for others later.

Here in McLennan County we’re experiencing a heat wave and a drought. Not altogether uncommon in Texas; and it will become increasingly common. We’re all being asked to reduce our water use, especially lawn irrigation, and to reduce our energy consumption in the peak afternoon hours.

In my house, we’re doing it. (In fact, our standard thermostat settings and water usage would probably strike some of our neighbors as self-punitive.) But I wonder how many residents of the county will comply? I’d put the over/under at 3%.

Americans in general are not good at self-limitation; and asking people to limit themselves is pretty much the only tool government has in these matters. This is the way it’s always been: you have electricity and water or you don’t. And when people have ongoing access to a resource they seem, almost inevitably, to think of that resource as infinite.

If there’s a way to make sure that people who absolutely need electricity still get it, I’d be fine with scheduled brownouts — in fact, I think that would be good policy in times when the grid is stressed. I’m not sure what the equivalent would be for the water system; but we need something, something that will conserve resources for a people who won’t voluntarily restrain their consumption.

The great thing about humility tweets is that you’re not trying to show that you are better than anybody else. You are showing that you are a regular, normal person, despite the fact that your life is so much more fabulous than those of the people around you. You are showing the world that you haven’t let your immense achievements go to your head! You’ve remained completely egalitarian — you just happen to be a better egalitarian than most people (and you are humbled by that fact). It’s easy to be humble when you’re most people. But just think about how amazing it is to be humble when you’re as impressive as you!

While plants do not demonstrate ESP or identify murderers, the fact that they are to some extent sentient, communicative, and social has been borne out by lots of recent scientific research far beyond what the polygraphers of Backster’s era might have imagined. At this point we know that plants can and do communicate among themselves and with other species: in forests, trees share information through underground mycelial networks, transmitting nutrients and news of climatic conditions through veins and roots and spores. It is through plant root structures that “the most solid part of the Earth is transformed into an enormous planetary brain,” according to Emanuele Coccia in The Life of Plants.

In an essay about nonhuman sociality, the anthropologist Anna Tsing says that plants do not have “faces, nor mouths to smile and speak; it is hard to confuse their communicative and representational practices with our own. Yet their world-making activities and their freedom to act are also clear — if we allow freedom and world-making to be more than intention and planning.” Tsing points out how bizarre it is that we have long assumed plants are not social beings — and that when we try to imagine them as such, it is through anthropomorphism: they are carnivorous murderers, or kindly creatures transmitting nature’s wisdom. Either way, the extent to which the plant is social depends on the extent to which the plant can socialize on our terms, with us. Who should speak for plants? Scientists? Filmmakers? Novelists?

Cf. this post.

To give an honest accounting of ourselves, we must begin with our weakness and fragility. We cannot structure our politics or our society to serve a totally independent, autonomous person who never has and never will exist. Repeating that lie will leave us bereft: first, of sympathy from our friends when our physical weakness breaks the implicit promise that no one can keep, and second, of hope, when our moral weakness should lead us, like the prodigal, to rush back into the arms of the Father who remains faithful. Our present politics can only be challenged by an illiberalism that cherishes the weak and centers its policies on their needs and dignity.

It’s very strange to think that someone who murders a convenience store employee in a botched robbery deserves another shot at life but someone who, say, was put on a list for having “creepy vibes” should have that fact scuttle his chances at getting a job years in the future. It’s very weird indeed. The best part of the anti-police state, anti-mass incarceration movement is its wise recognition that we are all fallen, all guilty, and a healthy and compassionate society is one that opens up many paths to second chances and redemption. And I say that with the authority of someone who has done bad things and had to ask forgiveness in turn.

In The Gulag Archipelago Solzhenitsyn says that whenever people in the Soviet Union were arrested they all said the same thing: “Me? What for?” When he was arrested that’s what he said too. Then, when he was brought before an official, preparatory to being stuffed into an interrogation cell, he had some papers thrust under his nose which he was told to sign. He signed them, he says, because “I didn’t know what else to do.”

When reading this passage I think about a couple of things. First, I remember James Scott’s book Seeing Like a State and its emphasis on all the ways that modern nation-states make us “legible” to its functions – and, perhaps even more important, teach us to believe that such legibility is necessary and vital. Second, I remember the comment that the anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss makes in Tristes Tropiques that throughout history the primary function of writing has been to enable slavery.

So into the belly of the beast Solzhenitsyn goes, and remains for several miserable years – but then, at a certain point, he begins what he calls his “ascent.” And the beginning of the ascent is marked by one of the most famous passages in all of twentieth century writing:

It was granted me to carry away from my prison years on my bent back, which nearly broke beneath its load, this essential experience; how a human being becomes evil and how good. In the intoxication of youthful successes I had felt myself to be infallible, and I was therefore cruel. In the surfeit of power I was a murderer, and an oppressor. In my most evil moments I was convinced that I was doing good, and I was well supplied with systematic arguments. And it was only when I lay there on rotting prison straw that I sensed within myself the first stirrings of good. Gradually it was disclosed to me that the line separating good and evil passes not through states, nor between classes, nor between political parties either — but right through every human heart — and through all human hearts. This line shifts. Inside us, it oscillates with the years. And even within hearts overwhelmed by evil, one small bridgehead of good is retained. And even in the best of all hearts, there remains… an unuprooted small corner of evil.

Bless you, prison, bless you for being in my life! For there, lying upon the rotting prison straw, I came to realize that the object of life is not prosperity, as we are made to believe, but the maturity of the human soul.

NOTE

If you want to know why Solzhenitsyn is truly great as a writer, you should take note of the very next sentence he writes: “(And from beyond the grave come replies: It is all very well for you to say that — you who came out of it alive!)”

It is after this that Solzhenitsyn begins to describe, not only the change in him, but the change in his relations with others. He no longer simply accepts the imposed and inflexible laws of the Gulag, he and his colleagues began to form strategies of resistance. When asked “Why did you put up with all that?” he answers that many of the prisoners did not – but it is absolutely essential, if you want to understand Solzhenitsyn, to realize that he was able to resist constructively only after he acknowledged his own personal guilt, only after he began a long process of repentance.

That is, Solzhenitsyn makes it quite clear that meaningful resistance begins with self-understanding. You can only make an intelligent attempt to alter your circumstances if you understand who you are, which means understanding that your own innate human nature is not different from that of your captors.

In Breaking Bread with the Dead, I write about Donna Haraway:

There’s a fascinating early chapter in her book on human interaction with pigeons. Of course, that interaction has been conducted largely on human terms, and Haraway wants to create two-way streets where in the past these paths ran only from humans to everything else. How to get the pigeons to participate willingly in such a project is question without an obvious answer, but it’s question that Haraway feels we must ask, a because “staying with the trouble requires making oddkin; that is, we require each other in unexpected collaborations and combinations, in hot compost piles. We become-with each other or not at all.”

But here’s the complication: Who gets included in “each other”? Besides pigeons, I mean. Haraway says explicitly that her human kin are “antiracist, anticolonial, anticapitalist, proqueer feminists of every color and from every people,” and people who share her commitment to “Make Kin Not Babies.” “Pronatalism in all its powerful guises ought to be in question almost everywhere.”

I suspect that — to borrow a tripartite distinction from the psychiatrist and blogger Scott Alexander — most people who use that kind of language are fine with their ingroup (“antiracist, anticolonial, anticapitalist, proqueer feminists of every color and from every people”) and fine with the fargroup (pigeons), but the outgroup? The outgroup that lives in your city and votes in the same elections you do? Maybe not so much. Does the project of making kin extend to that couple down the street from you who have five kids, who attend a big-box evangelical church, and who voted for the wrong person in the last presidential election? And who, moreover, are a little more likely to talk back than pigeons are? (Even assuming that they might be interested in making kin with Donna Haraway, which, let’s face it, is equally unlikely. Presumably they too would be more comfortable with the pigeons.)

I thought about these issues as I read an excerpt from James Bridle’s new book:

A system of laws and protections developed by and for humans, that places human concerns and values at its core, can never fully incorporate the needs and desires of nonhumans. These judicial efforts fall into the same category of error as the mirror test and ape sign language: the attempt to understand and account for nonhuman selfhood through the lens of our own umwelt. The fundamental otherness of the more-than-human world cannot be enfolded into such human-centric systems, any more than we can discuss jurisprudence with an oak tree.

Legal representation, reckoning, and protection are founded upon human ideas of individuality and identity. They may prove useful when we take up the case of an individual chimp or elephant, or even a whole species, but their limits are clear when we apply them to a river, an ocean, or a forest. A plant has no “identity;” it is simply alive. The waters of the earth have no bounds. This is both ecology’s meaning and its lesson. We cannot split hairs, or rocks, or mycorrhizal roots and say: This thing here is granted personhood, and this thing not. Everything is hitched to everything else.

The enactment of a more-than-human politics calls explicitly for a politics beyond the individual, and beyond the nation-state. It calls for care, rather than legislation, to guide it.

As regular readers might expect, this call for care, this ecological perspective, resonates powerfully with me. (It also resonates with something I wrote about in another book: Simone Weil’s insistence that if we need a collective declaration of human rights, we also, and perhaps more desperately, need a declaration of human obligations.)

But it is curious to me that many people are willing to entertain this line of thought, are immensely sympathetic to this line of thought, who also affirm that “in relation to the mind the body has no rights”; and that a fetus in the womb is but an insignificant “clump of cells.” I don’t think you can consistently hold all those views. If you are willing to ask, “What do we owe the more-than-human world?” then, I think, you must also be willing to ask, “What do we owe the fetus in the womb? What do we owe our own bodies?” If you’re not asking these questions, then I fear that the other affirmations are empty rhetoric — a make-believe extension of agency to things you can then safely ignore.

Tonight, I say this to my Republican colleagues who are defending the indefensible: there will come a day when Donald Trump is gone, but your dishonor will remain.

Joel Lehman and Kenneth O. Stanley (2011):

Most ambitious objectives do not illuminate a path to themselves. That is, the gradient of improvement induced by ambitious objectives tends to lead not to the objective itself but instead to dead-end local optima. Indirectly supporting this hypothesis, great discoveries often are not the result of objective-driven search. For example, the major inspiration for both evolutionary computation and genetic programming, natural evolution, innovates through an open-ended process that lacks a final objective. Similarly, large-scale cultural evolutionary processes, such as the evolution of technology, mathematics, and art, lack a unified fixed goal. In addition, direct evidence for this hypothesis is presented from a recently-introduced search algorithm called novelty search. Though ignorant of the ultimate objective of search, in many instances novelty search has counter-intuitively outperformed searching directly for the objective, including a wide variety of randomly-generated problems introduced in an experiment in this chapter. Thus a new understanding is beginning to emerge that suggests that searching for a fixed objective, which is the reigning paradigm in evolutionary computation and even machine learning as a whole, may ultimately limit what can be achieved. Yet the liberating implication of this hypothesis argued in this paper is that by embracing search processes that are not driven by explicit objectives, the breadth and depth of what is reachable through evolutionary methods such as genetic programming may be greatly expanded.

Late in their essay, Lehman and Stanley illustrate their point by describing the navigation of mazes: If you’re going to make your way from the periphery of a maze to the center, you have to be willing to spend a good bit of time moving away from your goal. A determination to go directly towards your goal will “lead not to the objective itself but instead to dead-end local optima.”

(I got to this by following some links from Samuel Arbseman’s newsletter.)

I think this insight has implications far beyond machine learning, and even beyond what Lehman and Stanley call “large-scale cultural evolutionary processes.” It’s true of ordinary human lives as well. When we define our personal goals too narrowly or too rigidly, we render ourselves unable to reach them — or to reach them only to discover that they weren’t our real goals after all.

There’s a wonderful moment in Thomas Merton’s The Seven-Storey Mountain when Merton — a new convert to Catholicism — is whining and vacillating about what he should be: a teacher, a priest, a writer, a monk, something else altogether maybe, a labor activist or a farm laborer. And his friend Robert Lax tells him that what he should want to be is a saint. It’s a marvelous goal not only because all Christians are called to be saints but also because there’s a liberating vagueness to the pursuit of sainthood. In his great essay on “Membership” C. S. Lewis comments that “the worldlings are so monotonously alike compared with the almost fantastic variety of the saints,” and it’s true: there are so many ways to be a saint, and you can never know which of them you’ll be called to take.

I think these thoughts may have some implications for secular vocations as well.

What the West Got Wrong About China – Habi Zhang:

The reason why China would brazenly “disregard the international law” that many other nations voluntarily abide by is that the rule of law is not, and has never been, a moral principle in Chinese society. […]

It was the rule of morality, not the rule of law, that defined Chinese politics.

In The Classics of Filial Piety — primarily a moral code of conduct — Confucius teaches that “of all the actions of man there is none greater than filial piety. In filial piety, there is nothing greater than the reverential awe of one’s father. In the reverential awe shown to one’s father, there is nothing greater than the making him the correlate of Heaven.” We can therefore conclude that the Durkheimian sense of the sacred object — the source of moral authority — is the father in both the literal and metaphorical sense. With this understanding, Confucianism can be viewed as a religion as manifested in the ritual of ancestor worship.

What the individual sovereignty is to liberalism, ancestor worship is to Confucianism.

Fascinating. James Dominic Rooney offers a partial dissent here — though it’s not to my mind especially convincing. David K. Schneider weighs in on the debate and comes down more on Zhang’s side: “liberal government is antithetical to the Confucian ideal of benevolent government. In Mencius, the happiness of the people is the measure of good government. But the people are not sovereign. Only a king is sovereign and conformity with Heaven’s ritual order is the responsibility of an educated political and economic elite, which is charged with the duty of acting as parents to the people, who in turn are obliged to submit.”

This argument sheds an interesting light on my recent essay on “Recovering Piety.”

We know that when Dickens wrote David Copperfield he had not read Kierkegaard’s Either/Or – published less than a decade earlier, available only in Danish – but when I reflect on one character from that novel, James Steerforth, I find it hard to believe that Dickens didn’t know the “Seducer’s Diary.” Steerforth’s seduction, abduction, and abandonment of David’s childhood love Emily (Little Em’ly, as her family call her) proceeds precisely according to the emotional sequence outlined in that diary. Johannes the Seducer and Steerforth are both perfect embodiments of what Emile Durkheim would later call anomie – a combination of amorality and unconquerable boredom, with the boredom generated by the amorality, though seducers think that by rejecting the moral laws of their societies they can make their lives more interesting.

More on anomie later. For now I want to focus not on Steerforth himself but on his family – his, and Emily’s. Dickens regularly juxtaposes Mrs. Steerforth, James’s mother, to Daniel Peggotty, Emily’s uncle and adoptive father; this juxtaposition is one of the most important elements of the book. When Steerforth sweeps Emily away, just on the eve of her marriage to her cousin Ham, and takes her to Europe, both families are devastated, but in very different ways.

When, soon after the lovers’ disappearance, Daniel Peggotty visits Mrs. Steerforth – he hopes to learn whether Steerforth is likely to marry Emily – the lady treats him to this discourse:

“My son, who has been the object of my life, to whom its every thought has been devoted, whom I have gratified from a child in every wish, from whom I have had no separate existence since his birth – to take up in a moment with a miserable girl, and avoid me! To repay my confidence with systematic deception, for her sake, and quit me for her! To set this wretched fancy, against his mother’s claims upon his duty, love, respect, gratitude – claims that every day and hour of his life should have strengthened into ties that nothing could be proof against! Is this no injury? […]

“If he can stake his all upon the lightest object, I can stake my all upon a greater purpose. Let him go where he will, with the means that my love has secured to him! Does he think to reduce me by long absence? He knows his mother very little if he does. Let him put away his whim now, and he is welcome back. Let him not put her away now, and he never shall come near me, living or dying, while I can raise my hand to make a sign against it, unless, being rid of her forever, he comes humbly to me and begs for my forgiveness. This is my right. This is the acknowledgement I will have. This is the separation that there is between us!”

To understand this outburst fully, we need to recall that earlier in the story, Mrs. Steerforth’s companion Rosa Dartle – a shrewd and ironic young woman embittered by her hopeless love for Steerforth – had, with a malicious false ingenuousness, asked Steerforth what might happen if “you and your mother were to have a serious quarrel.” To this Mrs. Steerforth replied, “My dear Rosa, … suggest some other supposition! James and I know our duty to each other better, I pray Heaven!”

“Oh!” said Miss Dartle, nodding her head thoughtfully. “To be sure. That would prevent it? Why, of course it would. Exactly. Now, I am glad I have been so foolish as to put the case, for it is so very good to know that your duty to each other would prevent it! Thank you very much.”

Rosa’s mock-inquiry arises from her understanding that Steerforth and his mother do not perceive their relationship in the same light: his “duty” would not, and in the end does not, prevent him from acting in what he perceives to be his interest, even when that interest is merely the avoidance of boredom. Rosa also understands that Mrs. Steerforth sees her relationship with her son contractually and legalistically: he owes her obedience and deference because, she says, he is the one “whom I have gratified from a child in every wish.” Thus her outrage at his failure to meet the terms of the contract is extreme and implacable: he is banished from her presence until he (a) abandons Emily forever and (b) begs his mother’s forgiveness. “This is the acknowledgement I will have.”

After she delivers herself of this announcement Daniel Peggotty takes his leave of her; there is no more to be said; their models of parental love are incommensurable, irreconcilable.

The vastness of the chasm between them may be seen by comparing Mrs. Steerforth’s distribe with Daniel Peggotty’s response when he learns that Emily has fled with her lover:

“I’m a-going to seek her, fur and wide. If she should come home while I’m away – but ah, that ain’t like to be! – or if I should bring her back, my meaning is, that she and me shall live and die where no one can’t reproach her. If any hurt should come to me, remember that the last words I left for her was, ‘My unchanged love is with my darling child, and I forgive her!’”

Call me a normie if you want, call me sentimental, what you will – I don’t know many things in all of fiction more moving than this. Let me wipe a tear from my eye and then take a moment to unpack both the explicit statements and the implications in Mr. Peggotty’s declaration.

- Emily is in need of forgiveness, for she has sinned. (Emily herself knows this perfectly well; she is nearly consumed with guilt.)

- Mr. Peggotty offers this forgiveness completely and without condition or reservation, no matter what Emily does or fails to do.

- He does not wait for her to beg forgiveness – he does not wait for her to repent or return – he’s “a-going to seek her, fur and wide.” The biblical analogue here is not the parable of the Prodigal Son, because there the son returns home on his own initiative. That story is lovely enough, with the old man seeing his son “a long way off” and, as Frederick Buechner has envisioned the scene, picking up his skirts and running as fast as his old legs will carry him to the beloved boy. But what Mr. Peggotty does calls forth something more radical still: “What man of you, having an hundred sheep, if he lose one of them, doth not leave the ninety and nine in the wilderness, and go after that which is lost, until he find it? And when he hath found it, he layeth it on his shoulders, rejoicing.”

- He knows that Emily will suffer for her sin; he knows that the way of the world – as exemplified, for instance, by Mrs. Steerforth – is not to forgive but rather to “reproach”; so he will do what he has to do, suffer whatever he needs to suffer, so that she will not be further wounded.

- His love for his “darling child” is “unchanged” – unchanged. Not altered in one fraction of a degree either by what she has done or what she has left undone, and never to be altered by anything in the whole wide reproaching world.

•

What most people want, or think they want, is affirmation. Indeed, many people demand it, and seek to punish those who do not give it to them. But affirmation never comes without conditions, even if they’re unstated. Thus I think it’s fair to say that Mrs. Steerforth, by explicitly indulging her son’s every wish while forever hinting that by so doing she is binding him contractually to her, is enriching the soil in which anomie flourishes. (Rosa Dartle sees all this coming, but because Steerforth does not return her love, she does nothing to avert it but merely waits for the inevitable crack-up. This may be a function of some inbuilt perversity of Rosa’s character, but I think it rather an outgrowth of her dependent status and Mrs. Steerforth’s contempt for her needs — that relationship too is contractual; it’s impossible to imagine Mrs. Steerforth having any other kind.)

What people need, whether they know it or not, is not affirmation but rather unconditional love – because only with unconditional love can there be genuine honesty. What Emily needs is not the fiction that she has done no wrong; what she needs, and what she receives, is the double truthfulness that she has indeed sinned but is wholly forgiven. It’s what she needs; it’s what we all need, and from those who genuinely love us we just may get it.

Perhaps the key theme in C. S. Lewis’s book The Abolition of Man is his emphasis on the importance, in much classical and almost all medieval thought, of the chest as the seat, the location, of our moral intuitions and convictions. Our mind cognizes and analyzes, the rest of our body simmers with passionate humors, but the chest synthesizes thought and impulse and converts that synthesis into meaningful moral action.

One of the chief appeals of social media, for many of us, is the ease with which we can “get something off our chest.” But maybe there are feelings and convictions that ought to remain on our chest, even if their presence burns us.

I should put my cards on the table here: In the past week we have, in multiple ways, seen the pervasive moral corruption of the socially-conservative and at-least-nominally-Christian world of which I have been a part (though an often discontented and uncomfortable part) most of my life. It is impossible for any fair-minded person to deny that that world has surrounded itself with a vast fortress of lies within which it hopes to take refuge: lies about the 2020 election, lies about immigrants to the USA, lies about its own commitments to “traditional morality,” lies about its adherence to biblical authority, lies about its embodiment of genuine masculinity. From within that fortress the cry continually comes forth, The woke libtards are trying to destroy us! — to which the most reasonable reply is: You’re destroying yourselves faster than any external enemies ever could.

And that’s as far as I’m going to go by way of getting anything off my chest. I could certainly continue the denunciations, and continue at great length — there’s no shortage of material. But I don’t want to consume my anger and pain by shoveling them into a red-hot social-media furnace. Denunciations do no good.

I want to keep my anger and pain close to me, inside me, even though it hurts, and find some proper outlet for them — as I say, to synthesize my thoughts and my feelings into meaningful moral action.

On this blog I will continue to focus my attention on praising the praiseworthy and celebrating the good, the true, and the beautiful, because that’s my calling, that’s my lane. As Bob Dylan once said, “There’s a lot of things I’d like to do. I’d like to drive a race car on the Indianapolis track. I’d like to kick a field goal in an NFL football game. I’d like to be able to hit a hundred-mile-an-hour baseball. But you have to know your place.” And my place, vocationally speaking, is not to be a politician or a pundit. It is, rather, to invite my readers to join with me in a quest to repair the world — from the inside of us out, as it were. To change hearts; to heal and strengthen the seat of our affections.

But that doesn’t mean that I can take no political or social action in response to the pervasive corruption I see and lament. I am asking myself some questions that I think all of us would do well to ask in these times: If there were no social media — no Twitter, no Facebook, no blogs even — what would I do? Whom would I seek to address and how would I address them? Would I use words only, or would I take action? And if the latter, what would proper action be? Imagine that all the familiar means of “getting things off my chest” were denied to me — what would I do then?

In the coming days I will be pondering those questions. And meanwhile, on this blog, regular service will resume next week.

A brief follow-up to my earlier post on effective altruism (EA): I have a feeling that what makes EA less effective than it aspires to be is its relentless presentism. EA always looks for strictly financial means to address a given problem and address it right now. But what if the interventions that make an immediate impact aren’t the ones that make the best long-term impact?

A decade ago Barbara H. Fried of Stanford Law School published an essay arguing that ethicists and legal scholars have a tendency to formulate all problems as trolley problems, in this sense:

The “duty not to harm” and conventional “duty of easy rescue” hypotheticals typically share the following three features: The consequences of the available choices are stipulated to be known with certainty ex ante; the agents are all individuals (as opposed to institutions); and the would-be victims (of the harm we impose by our actions or allow to occur by our inaction) are generally identifiable individuals in close proximity to the would-be actors). In addition, agents face a one-off decision about how to act. That is to say, readers are typically not invited to consider the consequences of scaling up the moral principle by which the immediate dilemma is resolved to a large number of (or large-number) cases.

I’m especially interested in the “one-off decision” business: What if interventions that are most effective in the short term are counter-productive in the long term? What if over the long haul attention to the cultivation of neighborliness is actually more effective? Something to consider.

There’s a good discussion of these matters in Matt Yglesias’s most recent newsletter.

In many of my courses I ask my students to explicate certain key passages from the texts we read — to dig in to the details, to see how the passages do their work. Here’s a selection from Solzhenitsyn’s Gulag Archipelago — the chapter called “The Ascent” — that some of my students are writing about:

You are ascending….

Formerly you never forgave anyone. You judged people without mercy. And you praised people with equal lack of moderation. And now an understanding mildness has become the basis of your uncategorical judgments. You have come to realize your own weakness — and you can therefore understand the weakness of others. And be astonished at another’s strength. And wish to possess it yourself.

The stones rustle beneath our feet. We are ascending….

With the years, armor-plated restraint covers your heart and all your skin. You do not hasten to question and you do not hasten to answer. Your tongue has lost its flexible capacity for easy oscillation. Your eyes do not flash with gladness over good tidings nor do they darken with grief.

For you still have to verify whether that’s how it is going to be. And you also have to work out — what is gladness and what is grief.

And now the rule of your life is this: Do not rejoice when you have found, do not weep when you have lost.

Your soul, which formerly was dry, now ripens from suffering. And even if you haven’t come to love your neighbors in the Christian sense, you are at least learning to love those close to you.

Those close to you in spirit who surround you in slavery. And how many of us come to realize: It is particularly in slavery that for the first time we have learned to recognize genuine friendship!

And also those close to you in blood, who surrounded you in your former life, who loved you — while you played the tyrant over them….

Here is a rewarding and inexhaustible direction for your thoughts: Reconsider all your previous life. Remember everything you did that was bad and shameful and take thought — can’t you possibly correct it now?

Yes, you have been imprisoned for nothing. You have nothing to repent of before the state and its laws.

But … before your own conscience? But … in relation to other individuals?

A slow day at the museum, and the receptionist is sitting at their desk as a stranger approaches, perhaps a tourist.

‘Hi’, the stranger begins, ‘I found this on the street just around the corner.’ He puts a wallet on the desk and pushes it over to the receptionist. ‘Somebody must have lost it. I’m in a hurry and have to go. Can you please take care of it?’. Without waiting for a response, the stranger turns and leaves.

The wallet is a clear plastic envelope, which the receptionist picks up and turns over. Inside they can clearly see a key, a shopping list, some business cards and a couple of bank notes.

So what happens to the envelope? That’s the question asked by Alain Cohn, a researcher at the University of Michigan, and his team — who have dropped off similar envelopes all over the world. Stafford continues:

For me, the most interesting finding is not whether most wallets were returned (they were), or whether the wallets with more money in were more likely to be returned (also true), but the differences around the world in the rates at which the wallets were returned. These differences were huge, varying from 4 out of every 5 wallets being returned (in Scandinavia, of course, and Switzerland), to fewer than 1 in 5 being returned (in places including China, Peru and Kazakhstan).

Trying to understand this range led Cohn and his team to the World Values Survey, an international research effort that polls citizens around the globe about their beliefs and attitudes. One question, in particular, asks about faith in other people: ‘Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted or that you need to be very careful in dealing with people?’. In Sweden, for example, most people agree with this statement. In Peru, fewer than 10 per cent do. Cohn’s analysis suggests that it is this generalised trust in other people that drives the cross-cultural differences seen with the lost wallets.

Stafford, following Cohn, thinks that the key variable here is “views of human nature,” but that’s not obviously correct. What if the key variable is “views of social responsibility”? I wonder if Cohn et al. asked any questions about that.

My point is simply that when a capability is acquired there is no longer a temporal interval between judging according to a universal rule and acting in a particular situation in the way Kant conceptualizes ethics—they are morally the same instant. Of course, the fact that a capability is embodied does not guarantee that you will act morally any more than acting according to conscience guarantees it. The act of recognizing a rule, judging how it can be applied in a particular context, and then applying it, reflects a different temporality from one where one acts according to a capability that is dependent on a collective form of life that sustains a transcendent vision. This, I think, is what Ghazali meant when he reputedly said: Oh! if only I had the implicit faith of the old women of Nishapur! Meaning: To live without having to go through the process of verification and application of moral rules, to live at once in the time of this world and the time of eternity.

Picking up on this point, Katherine Lemons argues — in a post that’s part of a series on this trope — that the three key elements of the faith of the old women of Nishapur are:

- Time: “They live in a temporality of simultaneity where the eternal is ever-present in everyday life. Such simultaneity enables ethical action (that is, action oriented toward the Hereafter) without the need to weigh, to calculate, or to reason. Ethical action, that is, whose telos is immanent to it.”

- Indifference: “The temporality of the old women’s knowledge emerges from a faith for which doubt is an irrelevant category. It also gives rise to indifference in the face of scholarly knowledge…. Thus, [one] old woman was reportedly unimpressed by Fakhr al-Din Al-Razi’s one thousand proofs of God’s existence, inciting envy in the scholar. Asad’s mother was likewise [uninterested] in defending Islam or extolling its virtues and her ‘embodied religion did not offer itself to hermeneutic methods.’”

- Obstinacy: One old woman “lives with the hereafter and it informs her decisions, even when everything in worldly life hangs in the balance. Her certainty … allows her to exhibit obstinacy in the face of temporal power.”

All this is reminiscent of what Rebecca West calls “idiocy” — something I have commended. It may also be related to another strategy I have commended, that of practicing silence, exile, and cunning. But I think I like these interlocking practices even more. I will have things to say about them in the future. I am always looking for resources to keep me committed to restoration and renewal while also protecting be from the always-present temptation of building fascist architecture of my own design.

Strong readings of the Iliad tend to focus on the final encounter between Achilles and Priam, and Achilles’ return of the body of Hector, Priam’s son, whom he has killed. To [Jasper] Griffin, that scene affirms the value of a human life in the face of death. To [James] Porter, it makes the Iliad a poem of war, not death: Homer, “however we understand the name,” reveals the inexplicable, violent loss of life, not just the finality of death. I agree with Porter, as it happens. But while Porter and Griffin engage in critical single combat, we may want to listen to how the Iliad actually ends. The last word does not belong to Priam or Achilles, but to the women of Troy. At the funeral of Hector, their ritual laments insist on one theme: their dependence on the deceased. He meant different things to each, we learn, but they all relied on him. This is a theme that Achilles, in his great wrath, has difficulty grasping. It is also a theme that, from the position of combative criticism, can escape attention. From the perspective of the women of Troy, however, it is painfully obvious that people can only flourish when they look after each other and, in shared ritual, take care of the dead.

My Hedgehog Review essay “Injured Parties” — on free speech, iniuria, charity, social and legal remedies, and strategic inattention — is unpaywalled, so please read!

I will make a prediction: Within not too short a span of time, not only conservatives but most liberals will recognize that we have been running an experiment on trans-identifying youth without good or certain evidence, inspired by ideological motives rather than scientific rigor, in a way that future generations will regard as a grave medical-political scandal.

I think this prediction will partly, but not wholly, come true. I do believe that there will be a change of direction, but for the most part it will be a silent one, an unspoken course correction; and on the rare occasions that anyone is called to account for their recklessness, they’ll say, as a different group of enthusiasts did some decades ago, “We only did what we thought was best. We only believed the children.” But they won’t have to say it often, because the Ministry of Amnesia will perform its usual erasures; and even the children who have been sacrificed on the altar of their parents’ religion, metaphysical capitalism, may not recognize or remember what was done to them.

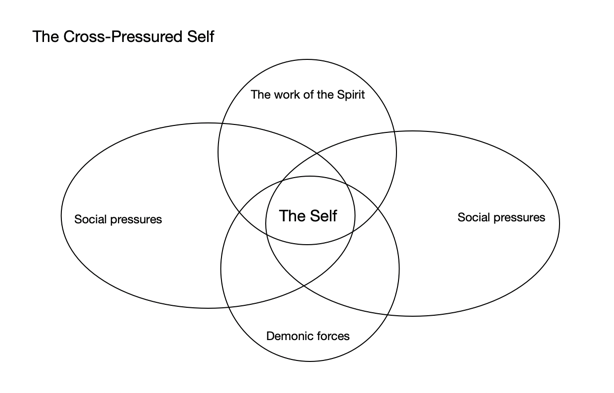

The same will be true of those who suffer the various derangements in what passes for the Right today. People will later briefly wonder at “all that happened to us, around us, and by us” — but then a notification will hit their phone and the wondering will cease. And the demonic realm will persist in its sleepless labor.

I’ll be back after Easter.

People on the left will typically be amazed and gratified by any good that has been achieved recently, and will treat any goods achieved by our ancestors as matters of course for which none of us need be grateful. Likewise, they are predisposed to see new developments as goods and are therefore unlikely to criticize them.

People on the right will typically be obsessively horrified by any new wrong, and uninterested in wrongs that have been long embedded in our social order — indeed, they will be so predisposed to see new developments as ills that they may, by way of compensation, grow inclined to see old ills as positive goods. But even if they see the ancient wrongs for what they are, they won’t feel their seriousness; it’s the new wrongs that engage their emotions.

In both cases, the looming power of the present moment distorts our judgment. Neophilia and neophobia alike occur because the present is so BIG that we can’t see around it; or because everything not-now seems small in comparison.

In other words, just as there are social discount rates for the future, there are also social discount rates for the past. And in both cases, our media environment encourages stronger and stronger discounts as we move away from the present moment (something that remains true even when the media try to tell us about climate catastrophe). But because the future has not occurred and could take many forms, it remains fuzzy for us, whereas the past can be seen more clearly. So I think that if we want people to have a stronger regard for future — to discount it less heavily — then, paradoxically, we need to make people more attentive to the past, its errors and its achievements alike.

In my recent post on neighborliness, I quoted from a sermon by Helmut Thielicke, and I want to return to one passage from that sermon:

Anybody who loves must always be prepared to have his plans interrupted. We must be ready to be surprised by tasks which God sets for us today. God is always compelling us to improvise. For God’s tasks always have about them something surprising and unexpected, and this imprisoned, wounded, distressed brother, in whom the Saviour meets us, is always turning up on our path just at the time when we are about to do something else, just when we are occupied with altogether different duties. God is always a God of surprises, not only in the way in which he helps us — for God’s help too always comes from unexpected directions — but also in the manner in which he confronts me with tasks to perform and sends people across my path.

It strikes me that it is just this kind of surprise that the Effective altruism (EA) movement is determined to avoid. It’s a movement that puts givers in complete control: they rationally calculate how much to give and to whom, and are on principle unmoved by other considerations.

My hero Paul Farmer used to say that as generous as WLs (White Liberals) can be, they tend to believe that the world can be repaired at no cost to themselves. If that’s true, then the difference between the WLs and the EAs is that the latter think the world can be repaired at no cost to themselves in anything other than money.

For an alternative model, I would suggest that everyone read this long and deeply moving story about an active, overflowing love that does not count costs — that gives all it has without calculation — that is wholly human-hearted.

P.S.

The epicenter of the EA movement seems to be in the Bay Area, and I wonder if that could be significant. If you are a very wealthy person who has to step over or around homeless people and drug addicts every day — or who at least has to hear regularly about your city’s crisis of homelessness and drug addiction — wouldn’t it be nice to have a Theory that explains why you don’t need to do anything about the problem? Maybe that’s too cynical, but I do wonder.

The search for the perfect rule or set of safety settings does remind me of Christine Emba’s Rethinking Sex. As she told me during our conversation, the modern culture around sex is marked by a broken promise. Many of her interviewees had a sense that, if you find the right rules, sex can only be good, and you and a stranger will never have to know each other or reveal yourselves to each other in order to feel good about what you do with each other. The rules (“two enthusiastically consenting adults”) will keep you safe.

But there’s no end run around character formation, and no checklist of consent items that lets us get around the fact that we are interacting with another human being, not a preference menu.

Christine’s book sounds absolutely brilliant, and I very much look forward to reading it. Leah’s conversation with Christine — I know both of them, thus the first names — is fascinating also. Such vital voices!

Re: my earlier post on an Ezra Klein column, I want to add that the universality of Christianity takes a very peculiar form, because it is a universality that also emphasizes neighborliness, a particular care for those who are nearby. Thus Matthew Loftus:

We cannot love “the whole world” except in abstraction, nor work for the mutual benefit of everyone in the same way that we can take care of our children or our sick neighbor. We must not fail in our duties to those close to us, even if our love ultimately does not stop there. Only by honoring the relationships that we have with others based on our common humanity and our common interchanges of trade and culture can we honor the God who created those people and places. Our local affections will have universal implications for how we use technology, farm the land, and execute trade. And in the global realm as well as the communal, love and sanity require limits.

I have forbidden the use of the EMR [Electronic Medical Records] in my mental health clinic at the hospital, at least for now. As I scribble my notes on paper, I look to the parent, sibling, child, or friend who has accompanied the patient to the clinic. When I ask how well the medications are working, sometimes the patient will say they are fine while their companion smiles and tells me the truth. Rarely do patients come alone; some friends or family members pay a day’s wages for an hour-long bus ride to the hospital to accompany their suffering loved one. I like to think that no one in our hospital suffers alone because the cultural ethos here forbids it.

Please do read the whole thing. But this is key: “Our local affections will have universal implications.” And, conversely, our universal commitments will necessarily have local instantiations.

I think Charles Dickens understood this paradox very well, as we see in the greatest of his novels, Bleak House. There we note Mrs. Jellyby practicing her “telescopic philanthropy” — meditating always on the suffering of the people of Borrioboola-Gha while utterly neglecting her own children — and the “business-like and systematic” charity of Mrs. Pardiggle. As Esther Summerson says, “Ada and I … thought that Mrs. Pardiggle would have got on infinitely better if she had not had such a mechanical way of taking possession of people.” When pressed by Mrs. Pardiggle to join in her “rounds,” Esther has a profound response (even if Mrs. P can’t grasp the import of it):

At first I tried to excuse myself for the present on the general ground of having occupations to attend to which I must not neglect. But as this was an ineffectual protest, I then said, more particularly, that I was not sure of my qualifications. That I was inexperienced in the art of adapting my mind to minds very differently situated, and addressing them from suitable points of view. That I had not that delicate knowledge of the heart which must be essential to such a work. That I had much to learn, myself, before I could teach others, and that I could not confide in my good intentions alone. For these reasons I thought it best to be as useful as I could, and to render what kind services I could to those immediately about me, and to try to let that circle of duty gradually and naturally expand itself.

Words to live by, say I. And let me conclude with words still wiser, from Helmut Thielicke’s great sermon on the Parable of the Good Samaritan:

You will never learn who Jesus Christ is by reflecting upon whether there is such a thing as sonship or virgin birth or miracle. Who Jesus Christ is you learn from your imprisoned, hungry, distressed brothers. For it is in them that he meets us. He is always in the depths. And we shall draw near to these brethren only if we open our eyes to see the misery around us. And we can open our eyes only when we love. But we cannot go and do and love, if we stop and ask first, “Who is my neighbor?” The devil has been waiting for us to ask this question; and he will always whisper into our ears only the most convenient answers. We human beings always fall for the easiest answers. No, we can love only if we have the mind of Jesus and turn the lawyer’s question around. Then we shall ask not “Who is my neighbor?” but “To whom am I a neighbor? Who is laid at my door? Who is expecting help from me and who looks upon me as his neighbor?” This reversal of the question is precisely the point of the parable.

Anybody who loves must always be prepared to have his plans interrupted. We must be ready to be surprised by tasks which God sets for us today. God is always compelling us to improvise. For God’s tasks always have about them something surprising and unexpected, and this imprisoned, wounded, distressed brother, in whom the Saviour meets us, is always turning up on our path just at the time when we are about to do something else, just when we are occupied with altogether different duties. God is always a God of surprises, not only in the way in which he helps us — for God’s help too always comes from unexpected directions — but also in the manner in which he confronts me with tasks to perform and sends people across my path.

P.S. I meant to schedule this to post tomorrow – sorry for all the stuff in one day. If I don’t post anything for the next day or two, just read this post several times. It’ll do you good.

“You have Putin’s Russia and Pushkin’s Russia,” Krielaars observed. To blame a whole culture, past and present, for a current political action implies that everything about that culture contributed to that action. If Germany succumbed to the Nazis, don’t listen to Beethoven; because of Mussolini, cancel Dante and Raphael; if you reject American actions in Vietnam, the Middle East, or anywhere else, no more Thoreau or Emily Dickinson. Could there be a better way to encourage national hatred than to treat a whole culture and its history as a unified whole, carrying, as if genetically, a hideous quality? […]

If Russian history teaches anything, it is that such “moral clarity” has no limits. If all right is on one side, then anything — literally anything — one says or does is justified. Indeed, to stop short of the most extreme measures is to indulge evil, which means risking the charge of complicity. When Stalin sent local officials quotas of people to be arrested, they responded by demanding still higher quotas. It was the safest thing to do to prove one’s loyalty. No one ever secured his position by calling for less severity to enemies. When everything is black and white, sooner or later everyone is at risk.

Well, it was very odd what Mr. Sammler found himself doing as he lay in his room, in an old building. Settling, the building had cracked its plaster, and along these slanted cracks he had mentally inscribed certain propositions. According to one of these he, personally, stood apart from all developments. From a sense of deference, from age, from good manners, he sometimes affirmed himself to be out of it, hors d’usage, not a man of the times. No force of nature, nothing paradoxical or demonic, he had no drive for smashing through the masks of appearances. Not “Me and the Universe.” No, his personal idea was one of the human being conditioned by other human beings, and knowing that present arrangements were not, sub specie aeternitatis, the truth, but that one should be satisfied with such truth as one could get by approximation. Trying to live with a civil heart. With disinterested charity. With a sense of the mystic potency of humankind. With an inclination to believe in archetypes of goodness. A desire for virtue was no accident.

New worlds? Fresh beginnings? Not such a simple matter. (Sammler, reaching for diversion.) What did Captain Nemo do in 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea? He sat in the submarine, the Nautilus, and on the ocean floor he played Bach and Handel on the organ. Good stuff, but old. And what of Wells’ Time Traveler, when he found himself thousands of years in the future? He fell in square love with a beautiful Eloi maiden. To take with one, whether down into the depths or out into space and time, something dear, and to preserve it — that seemed to be the impulse. Jules Verne was quite right to have Handel on the ocean floor, not Wagner, though in Verne’s day Wagner was avant-garde among the symbolists, fusing word and sound. According to Nietzsche the Germans, insufferably oppressed by being German, used Wagner like hashish. To Mr. Sammler’s ears, Wagner was background music for a pogrom. And what should one have on the moon, electronic compositions? Mr. Sammler would advise against that. Art groveling before Science.

— Saul Bellow, Mr. Sammler’s Planet

I have an essay in the new Hedgehog Review — behind a paywall, but shouldn’t you subscribe? Yes indeed you should. The essay is called “Injured Parties,” and it begins thus:

In 1923, the American movie star Dorothy Davenport lost her husband, the actor and director Wallace Reid, to an early death resulting from complications of morphine addiction. After the tragedy, Davenport took up the job — an unusual one for a woman in Hollywood in that era — of film producer. Starting with Human Wreckage, a movie about the dangers of drug addiction that appeared just months after Reid’s death, Mrs. Wallace Reid, as she now called herself, oversaw a series of films on pressing social issues. For instance, the third one she produced, and which she personally introduced in a prologue, The Red Kimono (1925), portrays the dark personal and social consequences of prostitution.

All of Davenport’s moral-crusading films were popular, but also controversial: Some were banned by the British Board of Film Censors and by the guardians of public morals in many American cities. The Red Kimono had other problems, though, problems related to one Gabrielle Darley. Darley was a young woman who in the second decade of the twentieth century had worked as a prostitute in Arizona for a pimp named Leonard Tropp. She fell in love with him and they moved to Los Angeles, where she gave him money to buy a wedding ring — for herself, she thought, but in fact Tropp planned to marry another woman. When Darley discovered this, she shot Tropp dead. In 1918, she was put on trial for murder, but had the great good fortune of being represented by an exceptionally eloquent defense attorney named Earl Rogers — a close friend of William Randolph Hearst — who presented her as having been, before meeting Tropp, “as pure as the snow atop Mount Wilson.” The jury couldn’t get enough of this kind of thing and enthusiastically acquitted Darley.

One of the journalists covering the trial was Rogers’s daughter, Adela Rogers St. Johns, who was already well on her way to earning her unofficial title as “World’s Greatest Girl Reporter.” (For many years she worked for Hearst newspapers, and may have reached the height of her fame in her reporting on the 1935 trial of Bruno Richard Hauptmann for kidnapping and murdering the young son of Charles and Anne Morrow Lindbergh.) She wrote a short story, based on the trial, called “The Red Kimono.” It caught the attention of Dorothy Davenport, who immediately commissioned a screenplay and started filming. The name she chose for the film’s protagonist? Gabrielle Darley.

I describe Darley’s claim to having been defamed by the film — to being injured reputationally — and the ultimate decision of the Supreme Court of California in her favor.

From there I go on to explore the meaning of defamation and how it has changed over time, with a particular focus on the early modern period, during which, as I learned from reading that wonderful scholar Debora Shuger, defamation was very differently understood. I indulge my suspicion that we — immured in a social-media environment for which defamation is more or less the coin of the realm — might have a few things to learn from that era, and also from Erving Goffman. Yeah, I know it sounds weird, but trust me, it all holds together. I think. Ultimately I am trying to imagine charity as both a legal and a social concept. The point of the essay is not to settle any current issues but rather, by looking into the past, to discover alternative and superior moral vocabularies with which to address our disagreements.

Subscribe and read, please!

Rebecca Newberger Goldstein, from Plato at the Googleplex: Why Philosophy Won’t Go Away:

Socrates was probably the first to identify aretē with what is — in terms of a person’s moral makeup or moral character — analogous to the health in that person’s body. A person doesn’t have to be recognized as healthy in order to be healthy, and so it is with Plato’s Socrates’ aretē. In the myth of the Ring of Gyges, presented in the Republic, Plato argues that even if a person could get away with all manner of wrongdoing while maintaining a good reputation because of a magic ring that renders him invisible, still he should not do any of these awful things, since by destroying his aretē the man will destroy himself. Aretē then is entirely independent of social regard. And in the Gorgias, Socrates is presented as asserting something so radical that his hearers think it has to be a joke. He would, he says, rather be treated unjustly than treat others unjustly (469c). But if aretē is conceived of as analogous to the health of the body, then Socrates’ statement is hardly absurd. The injustice that we do involves us far more intimately than the injustice that we suffer.

Behind these biases lies a more general failing, which the Dutch primatologist Frans de Waal calls “anthropodenial”: the denial that we are animals of a certain type (the anthropoid type), and the tendency to imagine ourselves, instead, as pure spirits, “barely connected to biology.” This mistaken way of thinking has a long history in most human cultures; it remains stubbornly lodged in people’s psyches even when they think they are examining the evidence fairly. Anthropodenial has led, until recently, to a reluctance to credit research findings that show that animals use tools, solve problems, communicate through complex systems, interact socially with intricate forms of organization, and even have emotions such as fear, grief, and envy. (This is a bait-and-switch: emotions have long been denigrated on the grounds that they are not pure spirit, and yet humans also want to claim a monopoly on what they despise.)

A fascinating and provocative essay on several levels.

Juliette Kayyem, who among other things is a security consultant:

But what if the essence of a place is that it is defenseless? What if its ability to welcome others, to be hospitable to strangers, is its identity? What if vulnerability is its unstated mission? That is the challenge I hadn’t considered….

In security, we view vulnerabilities as inherently bad. We solve the problem with layered defenses: more locks, more surveillance. Deprive strangers of access to your temple, I urged the committee members [at Tree of Life Synagogue in Pittsburgh], and have congregants carry ID. They would have none of it. Access was a vulnerability embedded in the institution, and no security expert could change that — we do logistics, not souls.

The standoff in Colleyville ended with the attacker dead and the hostages unharmed. But all around the country, synagogues are no doubt convening their security committees, wondering what more they can do to defend their members without losing their essential vulnerability. A synagogue is not like an airport or a stadium. When it becomes a fortress, something immeasurable is lost.

Continuing here to lay the groundwork for future reflection, opening questions rather than answering them….

Lately I have been musing over something the great Fleming Rutledge wrote a month or so ago: “I don’t like the word ‘practices.’ We have a mighty, implacable, shape-shifting Enemy so we need strategies.”

I agree with this emphasis wholly, except … what if the central practices of the Christian faith themselves constitute a strategy, indeed are the essential strategy? Mightn’t those practices be like the ones that Daniel learns from Mr. Miyagi in The Karate Kid – seemingly pointless or trivial habits and skills that turn out to be the most important ones to have in a time of great need?

I think this is the point that Lessle Newbigin makes in that essential book The Gospel in a Pluralist Society:

Because Jesus has met and mastered the powers that enslave the world, because he now sits at God’s right hand, and because there has been given to those who believe the gift of a real foretaste, pledge, arrabōn of the kingdom, namely the mighty Spirit of God, the third person of the Trinity, therefore this new reality, this new presence creates a moment of crisis wherever it appears. It provokes questions which call for an answer and which, if the true answer is not accepted, lead to false answers. This happens where there is a community whose members are deeply rooted in Christ as their absolute Lord and Savior. Where there is such a community, there will be a challenge by word and behavior to the ruling powers. As a result there will be conflict and suffering for the Church. Out of that conflict and suffering will arise the questioning which the world puts to the Church. This is why St. Paul in his letters does not find it necessary to urge his readers to be active in evangelism but does find it necessary to warn them against any compromise with the rulers of this age. That is why it was not superiority of the Church’s preaching which finally disarmed the Roman imperial power, but the faithfulness of its martyrs.

The question then is: How to form Christians in such a way that they are capable of undergoing martyrdom? (In any of its forms: red, green, or white.)

I am convinced that this is indeed a matter of cultivating the proper practices – which include words and deeds alike, by the way, or rather speech and writing understood as deeds: as Newbigin goes on to say, the fact that the witness of the martyrs was so exceptionally powerful does not abrogate the need for faithful preaching – indeed, faithful preaching was surely one of the means by which the martyrs were formed: “The central reality is neither word nor act, but the total life of a community enabled by the Spirit to live in Christ, sharing his passion and the power of his resurrection. Both the words and the acts of that community may at any time provide the occasion through which the living Christ challenges the ruling powers. Sometimes it is a word that pierces through layers of custom and opens up a new vision. Sometimes it is a deed which shakes a whole traditional plausibility structure. They mutually reinforce and interpret one another. The words explain the deeds, and the deeds validate the words.”

Preaching and praise, fasting and penitence, reading and serving – all are core practices of the Church. But as Lauren Winner has convincingly and troublingly argued, that may be more complicated than it sounds. More on the difficulties in a later post, I suspect.

In his great essay “Literature as Equipment for Living,” Kenneth Burke argues that proverbs may be described as a kind of purposeful realism (my phrase, not his):

Here there is no “realism for its own sake.” There is realism for promise, admonition, solace, vengeance, foretelling, instruction, charting, all for the direct bearing that such acts have upon matters of welfare.

Then Burke suggests: What happens if we think of all literature that way? “Proverbs are strategies for dealing with situations” – maybe all works of literary art do the same, just in different and more complex ways. If so, you need sociological categories for thinking about literature:

What would such sociological categories be like? They would consider works of art, I think, as strategies for selecting enemies and allies, for socializing losses, for warding off evil eye, for purification, propitiation, and desanctification, consolation and vengeance, admonition and exhortation, implicit commands or instructions of one sort or another. Art forms like “tragedy” or “comedy” or “satire” would be treated as equipment for living, that size up situations in various ways and in keeping with correspondingly various attitudes. The typical ingredients of such forms would be sought. Their relation to typical situations would be stressed. Their comparative values would be considered, with the intention of formulating a “strategy of strategies,” the “over-all” strategy obtained by inspection of the lot.

What Burke calls “the ‘over-all’ strategy” might be a synonym for the “general theory” I described, with reservations, in a recent post. But let’s set that aside for now, and think about equipment.

In his letter to the Ephesians, St. Paul writes,

The gifts he gave were that some would be apostles, some prophets, some evangelists, some pastors and teachers, to equip the saints for the work of ministry, for building up the body of Christ, until all of us come to the unity of the faith and of the knowledge of the Son of God, to maturity, to the measure of the full stature of Christ. We must no longer be children, tossed to and fro and blown about by every wind of doctrine, by people’s trickery, by their craftiness in deceitful scheming. But speaking the truth in love, we must grow up in every way into him who is the head, into Christ, from whom the whole body, joined and knit together by every ligament with which it is equipped, as each part is working properly, promotes the body’s growth in building itself up in love.

This is an astonishingly rich passage, but let’s begin exploring it by looking at one phrase: “to equip the saints.” The relevant word there, katartismon (καταρτισμὸν), appears in this one biblical location only, but it’s related to a whole complex of words that are dispersed throughout the letters of the New Testament. You’ll probably recognize the two parts: kat (down) and artisimon (shaped, formed, adjusted). The meaning is “adjusted just so” or “shaped just right” – which is why you sometimes see it translated “perfected,” though I don’t prefer that meaning. Throughout ancient Greek you see versions of this concept:

- ἐναραρίσκω (to fit or fasten in, to be fitted in)

- ἐπαραρίσκω (to fit to or upon, fasten to, to fit tight or exactly)

- προσαραρίσκω (to fit to, to be fitted to, firmly fitted)

- συναραρίσκω (to join together, to hang together)

The core idea is that of good workmanship, of something well-crafted. Closely related (thematically though not etymologically) is a passage from earlier in the letter to the Ephesians in which Paul says that we are the craftwork of God – esmen poiēma ktisthentes en Christō lēsou epi ergois agathois – poems made in Christ Jesus for good works.

The particular craft that seems to be contextually lurking behind all these terms is carpentry, and more specifically joinery – making the joints snug and tight and the surfaces smooth, so that the work thus crafted will hold together when it’s stressed or buffeted. That said, in the long passage quoted above Paul moves easily from the image of a well-made case to the image of a well-knitted body – because a body, being organic, will be not just soundly made but also capable of increasingly varied and challenging actions. A healthy body is more capable and adaptable than a well-crafted case because it can grow in size and strength, and improve in dexterity. (A body as old and decrepit as mine can still learn a new trick or two; even now I can through exercise increase not just my muscular power but even the density and strength of my bones.)

Still, it’s impossible not to remember that the art or craft in which the young Jesus was trained was that of a builder, a tekton.

To be equipped, then, in Paul’s sense, is not a matter of “the things we carry” but rather the formation we have undergone. (The German word Bildung doesn’t refer to building, rather to imaging — Bild means image — but the correspondence of the two words is a lovely accident.) Christian formation is equipment not in the sense of having the right tools but rather of being properly built, which means, chiefly, having the right habits – but no: the right habitus. The whole panoply of customary actions and perceptions located in one’s body, and one’s mind, and one’s social surround. (My brothers and sisters in Christ are part of my habitus.)

To return to Kenneth Burke: What if we were to think of literature and the other arts as a kind of repository of habitus, a motley collection of practices and strategies? “Motley” because we can never adopt them simply and straightforwardly – we have to accept the inevitability of bricolage. But still: experiences not just to admire or appreciate but to use. Edward Mendelson’s idea of “literature as a special form of intimacy” seems relevant here – literature, and the other arts, as equipment for living, equipment shared by fallen mortals, thinking reeds, puzzled people in the process of being formed. An improvised sociology for wayfarers.

In a key passage of A Secular Age, Charles Taylor writes: