Around fifteen years ago I published these thoughts in First Things. I’m reposting here because I am re-reading Grahame’s great book right now and taking my usual comfort and delight from it.

- The Annotated Wind in the Willows by Kenneth Grahame, edited by Annie Gauger. W.W. Norton, 480 pages, $39.95

- The Wind in the Willows: An Annotated Edition by Kenneth Grahame, edited by Seth Lerer Belknap/Harvard, 288 pages, $35

My history as a reader is an odd one. I began, conventionally enough, with Dr. Seuss, but at some point soon thereafter I decided that I didn’t want to read children’s books anymore. Instead, I wanted to read what my parents and grandmother were reading and refused to look at anything else. So the delights of Charlotte’s Web and The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe passed me by, immersed as I was in the Perry Mason mysteries of Erle Stanley Gardner, the space operas of Robert A. Heinlein, and the manly adventures of Louis L’Amour’s Sackett. Between the ages of six and fourteen or so, I fed my imagination with such treats. What that explains about my adult state of mind I leave as an exercise for others to say.

As I got older I encountered the occasional children’s classic — I read the Narnia books and The Hobbit in graduate school, as palate-cleansers after heavy courses of Derrida and Foucault — but it was only when my own son was born that I discovered Beatrix Potter and Goodnight Moon and Stuart Little and (a little later on) Adam of the Road and Farmer Boy and Susan Cooper’s The Dark Is Rising series. Those were wonderful days: In them, delight masqueraded as duty, for how could I read those books to Wes if I hadn’t read them myself first?

Best of all were those winter evenings when I crawled into bed and grinned a big grin as I picked up our lovely hardcover edition of Kenneth Grahame’s The Wind in the Willows, with illustrations by Michael Hague. Before I cracked it open I knew I would like it, but I really never expected to be transported, as, evening by evening, I was. After the first night (I read only one chapter at a stretch), I wanted the experience to last as long as I could possibly drag it out. It was with a sigh compounded of pleasure and regret and satisfaction in Toad’s successful homecoming that I closed the book. I knew I would read The Wind in the Willows many times, but I could never again read it for the first time.

Kenneth Grahame’s masterpiece was published just over a hundred years ago, which accounts for these two new annotated editions. One is edited by Annie Gauger, an independent scholar with an evident devotion to Grahame; this book is the work of a true fan, and I mean by that no denigration whatsoever. The other is edited by Seth Lerer, a professor of English and the author of the superb Children’s Literature: A Reader’s History; his affection for Grahame’s work is palpable, but his tone is rather more detached — properly so, I would say, but then, I am a professor of English myself.

It should come as no surprise that these two editors approach the story of The Wind in the Willows in significantly different ways. Gauger, the fan, holds an essentially Romantic view of authorship, according to which a book is likely to be, as Wordsworth put it, the result of a “spontaneous overflow of powerful emotion.” She offers much more biographical detail than Lerer — including many family pictures and transcribed or photographed letters and drawings — and is more prone to see characters and events as transmuted versions of Grahame’s own experiences. This tendency is evident on the first page, as Mole, moved by the new springtime’s “spirit of divine discontent and longing,” suddenly decides he has had enough of spring cleaning: “He suddenly flung down his brush on the floor, said ‘Bother!’ and ‘O blow!’ and also ‘Hang spring-cleaning!’ and bolted out of the house without even waiting to put on his coat.” It seems obvious to Hauger that this scene “mirrors Grahame’s longing to escape from his London job as secretary of the Bank of England.”

Well, maybe. Grahame didn’t like his job very much, though he obviously did it well, else he would not have risen so high so quickly: Grahame was named to the post of secretary (the head of the bank) at the remarkably early age of thirty-nine. It was not the career he would have chosen; he preferred to write. But his options were limited. Grahame was born in Edinburgh in 1859, a few weeks before Arthur Conan Doyle was born in the same city. His mother died when he was young and he was effectively abandoned by his alcoholic father, who left the boy to be reared by relatives in Berkshire — in Cookham, specifically, on the Thames, in a landscape young Grahame adored and largely recreated in The Wind in the Willows. His hope was to go up to Oxford, but his guardians lacked the necessary funds, so he was sent at age eighteen to London to work as a clerk. Two years later he moved to the bank and stayed there for the rest of his career.

And he did write: In the 1880s and 1890s he published many brief, light essays on a wide range of subjects and collected them in books that were well regarded; but after his marriage in 1899, and the birth of his son Alastair (called “Mouse”) a year later, the writing largely dried up. This could have been because his literary energies went into the stories he told Mouse — many of them about the misadventures of one Mr. Toad — or because of ill health, which Grahame suffered from chronically. There was also, in 1903, an odd incident at the bank, in which a strange man came in with a pistol and, for reasons never discovered, shot at Grahame repeatedly. Though all the shots missed, Grahame was understandably traumatized and began to come to the office less and less frequently. In 1908, the same year The Wind in the Willows was published, he retired. He was forty-nine.

So, does Mole’s repudiation of his spring-cleaning duties really mirror Grahame’s longing to escape from his job? The claim would be more convincing if he had written that scene a decade earlier, when he was still working at the bank full-time and striving to reach its highest place. But he had already effectively withdrawn from the workplace by the time he wrote about Mole. Maybe there’s not such a direct route from experience to art, and maybe Grahame was writing about what he said he was writing about: the “divine discontent” that the coming of spring is apt to prompt in any of us — in all of us.

The annotator’s temptation is to believe that every literary effect has an identifiable real-life cause, and Gauger succumbs to that temptation often. Because this book arose in stories told (or written as letters) to young Alastair Grahame, Gauger seeks to make Mouse something like the coauthor of the tale — a thought kindly meant, especially since Mouse was a deeply unhappy child who took his own life at the age of twenty, which utterly crushed his parents — but this is not wholly convincing. There also seems to be a degree of job-justification going on, with many comments exceeding the bounds of usefulness and decorum. Ratty’s brief reference to Mole’s stock of bottled beer — “‘I perceive this to be Old Burton,’ he remarked approvingly” — leads Gauger to two pages of information about the history of English brewing, capped with a recipe for mulled ale. Most distressing, I think, is what follows the narrator’s comment that “Toad listened eagerly, all ears”: “Toads do not have external ears, but they do have internal eardrums behind their eyes.” Oh no. Oh no, no, no.

Gauger’s edition is the most recent in a series of “Annotated” books that W.W. Norton has been publishing for many years. The first, and still the best, was Martin Gardner’s magnificent Annotated Alice (of Wonderland, that is), followed closely by Leslie Klinger’s multivolume Sherlock Holmes series. These are all tall, heavy books, expensively produced, and it’s clear that editorial policy is to risk over-annotation rather than leave anything uncommented on. But the Alice books and the Holmes stories have a density of texture — stemming in the one case from the intellectual playfulness, in the other from social detail — that allows them to bear a great many notes without sinking. The more delicate Wind in the Willows is overwhelmed by such treatment.

It is a pleasure, then, to turn from the Norton edition to the one Seth Lerer has prepared for Harvard. This Wind in the Willows is a little shorter, a little wider, and it opens quite easily on the reader’s lap. The pages have a slight gloss, the typeface is elegant; the margins are pleasingly wide, and the annotations are terse, informative, and properly infrequent. (Lerer, however, is enamored of the Oxford English Dictionary and cites it too often. Though he is doubtless right that in the hundred years since Grahame published his book, some of its language has become “more evocative than meaningful,” do we really require a note on the adverb “paternally”?)

The images are also well chosen, and there are fewer of them than in Gauger’s edition. I don’t know whether it’s really possible to read Gauger’s Wind in the Willows as a story — there’s so much stuff in it that, after turning a page, I often struggled to discern where the tale picks up again — but reading Lerer’s edition is a great pleasure. The notes are there when you need them and are easy to ignore when you don’t. This book is, among other things, a delightful testimony to the bookmaker’s art.

And, as I have already suggested, I prefer Lerer’s approach to the text, which, while not ignoring the biographical connections, is more interested in the literary, historical, and cultural antecedents. Lerer is highly attentive to Grahame’s borrowings of his nature imagery from the Romantic poets. Like C.S. Lewis, he sees the book as deeply evocative of its late-Victorian and Edwardian time and place. (Lewis: “Consider Mr. Badger — that extraordinary amalgam of high rank, coarse manners, gruffness, shyness, and goodness. The child who has once met Mr. Badger has ever afterwards, in its bones, a knowledge of humanity and English social history which it could not get in any other way.”)

In his introduction to the book, Lerer does a fine job of showing how The Wind in the Willows so beautifully balances the Edwardian love of the rural idyll, and its cult of domesticity, with its fascination with new technologies. Ratty’s old boat and Toad’s motorcar receive equal attention. Lerer resists the temptation to over-explain: He knows that there’s a magic in this story for which we have no critical means of accounting. His edition will be the one I return to when the book, as it often does, calls out to me and in its quiet and gracious tones requests my attention.

Now, about Toad’s ears. Let’s leave aside the question of the hearing apparatus of toads and consider, rather, the physiognomy of Toad—Toad of Toad Hall, that is. We should probably first note that the phrase “all ears” is what I believe is called an idiom and could well be applied to any number of creatures who lack actual ears. But there are more significant matters to contemplate. At one point we find Toad “arrayed in goggles, cap, gaiters, and enormous overcoat,… swaggering down the steps, drawing on his gauntleted gloves.” This is instructive. Later in the book Toad famously exchanges prison garb for the clothing of a washerwoman and for a time at least is able to pull off this impersonation. (He is helped in this feat by his “gaoler’s daughter,” a kind girl, and, it might be noted, “he could not help half-regretting that the social gulf between them was so very wide, for she was a comely lass, and evidently admired him very much.”) Another time we are told that “Toad fell on his knees among the coals and, raising his clasped paws in supplication” — Wait, “paws”?

His friends’ appearance is similarly described. They wear dressing gowns and slippers in the evenings: Badger’s “carpet slippers…were too large for him and down at heel,” but Mole possesses a “black velvet smoking-suit” that Ratty much admires. (When Mole, however, first digs out of his house and reaches the sunlit meadow, we see him “jumping off all his four legs at once.”) When Ratty and Mole get lost in the snow and are rescued by their fortuitous discovery of the door to Badger’s house, they are wearing “coats and boots” — we know because Badger invites them to remove those wet things when he welcomes them into his warm snug home.

What problems Grahame has posed for his illustrators! Should they simply draw humans with animal heads, or should Toad’s body be at least somewhat toadlike, Badger’s badgeresque, and so on? Moreover, how big should they be? If you read the text in a literalist spirit, you’ll have to conclude that the creatures shrink and expand according to narrative need and that their appendages turn from paws to hands and back again, depending on the circumstances.

In Michael Hague’s adroit and precise paintings for the 1980 Henry Holt edition, Toad the washerwoman is depicted as about four feet tall — just large enough to pass, maybe — while Mole and Rat as they stand before Pan are the size of real moles and rats. And yet when Hague portrays the four friends together, they’re all the same size. Gauger shows us a painting from a beautiful 1913 edition in which the gifted artist Paul Bransom portrays Toad with the gaoler’s daughter, and he’s just a toad. A little on the large side, but plausibly so. And he’s naked, as toads tend to be. But how could such a creature ever have driven an automobile? And what happened to his goggles?

Perhaps it’s best not to inquire too deeply into such matters, if one does not have to. One of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, George Peele, wrote a play in which an old woman, Gammer Madge, starts telling a story: “Once upon a time, there was a king, or a lord, or a duke, that had a fair daughter, the fairest that ever was; as white as snow and as red as blood: and once upon a time his daughter was stolen away: and he sent all his men to seek out his daughter; and he sent so long, that he sent all his men out of his land.” This prompts one of her listeners to ask, “Who dressed his dinner, then?” But Madge quickly replies, “Nay, either hear my tale, or kiss my tail.”

A just rebuke. God bless Grahame’s illustrators in their impossible task, but for readers the characters’ various species surely telegraph key traits. Mole squints in the sunlight, uneasy and unadept with his big claws in the sunlit world of the river, but eager and growing in boldness. Ratty is wiry, quick, resourceful. Badger is stubborn, of course, set in his ways, but kind, as Lewis remarks, and simply good. Toad leaps about, his eyes bulging, his cheeks puffing — and then collapses on himself, making a heap of self-pity. These are very different creatures, and yet they are dear friends.

And that’s the point. C.S. Lewis is good on this. In The Four Loves he writes, “The quaternion of Mole, Rat, Badger, and Toad suggests the amazing heterogeneity possible between those who are bound by Affection,” and in his essay “Membership” he writes, “A trio such as Rat, Mole, and Badger symbolizes the extreme differentiation of persons in harmonious union, which we know intuitively to be our true refuge both from solitude and from the collective.” Toad is omitted from the second sentence because, as I have commented elsewhere, he is too chaotic to be in a state of “harmonious union” with anyone else. His friends know that, and they love him all the same, though often with an exasperated sort of tenderness.

If we must claim that The Wind in the Willows is about something, I would say that it’s mostly about the inter-animating powers of friendship and place. Ratty loves the river, but he loves it more when he can show it to Mole. Ratty has known all along that “there is nothing — absolutely nothing — half so much worth doing as simply messing about in boats,” but he chants this well-worn fact over and over, dreamily, because in sharing the experience with the novice Mole he finds it coming fully alive to himself once more. Badger’s home is all the more delightful as a refuge from the cold because it is Badger’s home, not just some generic warm spot. Badger’s gruff hospitality allows all sorts of creatures to come and go as they will. And Toad Hall becomes more wonderful than ever when it has been saved from the stoats and weasels, and saved by Toad’s faithful friends. Friends give meaning to a place, and the traits of certain places encourage and strengthen the blessings of friendship.

These are great lessons for anyone to learn, or to remember, at any age. And no book shows us these relations so beautifully as The Wind in the Willows.

The book is frankly an idyll, but, if I may risk the introduction of some disharmony into this meditation, I have to say that there are two distinct tribes of Wind in the Willows lovers: those for whom Toad is what it’s all about, and those for whom the milder adventures of Rat and Mole are the heart of the matter.

In my experience, young children tend to be in the former camp, their parents in the latter. (Grahame himself seems to have been uncertain: He had finished the book without arriving at a title, and as it was being passed around to publishers it was known variously as The Mole and the Water Rat and Mr. Toad.)

As an adult discoverer of Grahame’s riverine world, I must admit that I have always found that the Toad is too much with us. To be sure, his escapades are delightful and delightfully told — but I always find myself thinking, “Can we get back to Mole and Ratty now?” When I read the book the first time to my young son, it was obvious to me that Wes felt just the opposite. I still remember his belly laugh at Toad’s response to his first encounter with an automobile, one that nearly runs him and his friends down: “Toad sat straight down in the middle of the dusty road, his legs stretched out before him, and stared fixedly in the direction of the disappearing motorcar. He breathed short, his face wore a placid satisfied expression, and at intervals he faintly murmured ‘Poop-poop!’”

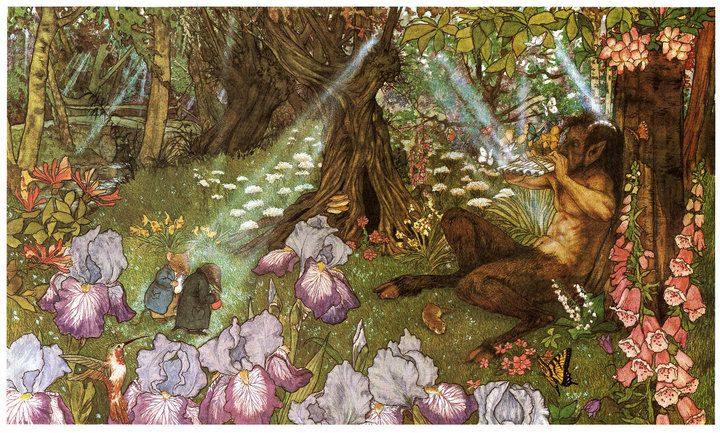

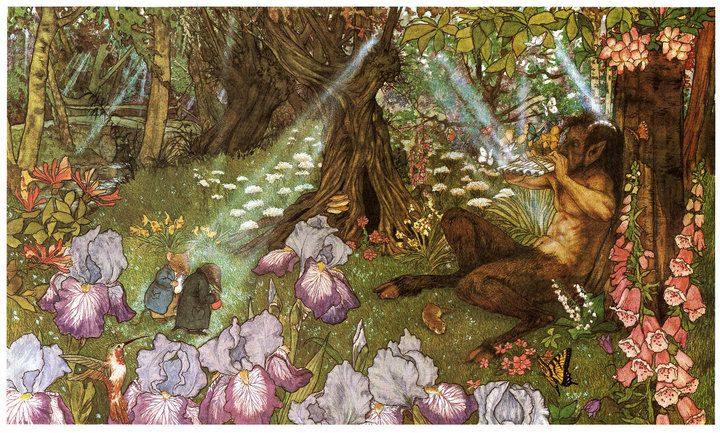

The Wind in the Willows is surely the most beautifully written of all children’s books — it offers to the willing learner a deep course in the making of sentences — and its finest prose may be found in the famous chapter 7: “The Piper at the Gates of Dawn.” This is when Rat and Mole, searching the river for a lost baby otter named Portly, find themselves drawn by a distant haunting melody to a small island:

Perhaps he would never have dared to raise his eyes, but that, though the piping was now hushed, the call and the summons seemed still dominant and imperious. He might not refuse, were Death himself waiting to strike him instantly, once he had looked with mortal eye on things rightly kept hidden. Trembling he obeyed, and raised his humble head; and then, in that utter clearness of the imminent dawn, while Nature, flushed with fullness of incredible color, seemed to hold her breath for the event, he looked in the very eyes of the Friend and Helper; saw the backward sweep of the curved horns, gleaming in the growing daylight; saw the stern, hooked nose between the kindly eyes that were looking down on them humorously, while the bearded mouth broke into a half-smile at the corners; saw the rippling muscles on the arm that lay across the broad chest, the long supple hand still holding the pan-pipes only just fallen away from the parted lips; saw the splendid curves of the shaggy limbs disposed in majestic ease on the sward; saw, last of all, nestling between his very hooves, sleeping soundly in entire peace and contentment, the little, round, podgy, childish form of the baby otter. All this he saw, for one moment breathless and intense, vivid on the morning sky; and still, as he looked, he lived; and still, as he lived, he wondered.

“Rat!” he found breath to whisper, shaking. “Are you afraid?”

“Afraid?” murmured the Rat, his eyes shining with unutterable love. “Afraid! Of him? O, never, never! And yet — and yet — O, Mole, I am afraid!”

The language here goes right to the brink of over-sweetness — but that is precisely what it must do, as it strives to describe experiences so good, so powerful, that they overtax the human imagination.

In a recent article in the Guardian of London, Rosemary Hill wrote of this scene, “Whether it is the latent homoeroticism of the vision or simply the sudden change of tone that makes the scene so uncomfortable, it is certainly a failure.” Now, when people talk about “latent homoeroticism” in the Iliad, or in the biblical story of David and Jonathan, even if I might read those passages differently, I at least know what they’re talking about, but Rosemary Hill leaves me speechless. Who exactly is hot for whom in this scene? And why does Hill say that the scene itself is uncomfortable, when all the discomfort surely lies with her? The lack of imagination here, the rote recital of contemporary shibboleths, is discouraging.

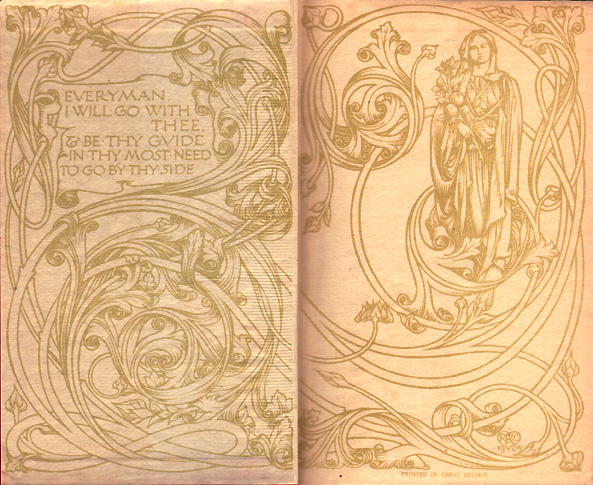

Yet the encounter with Pan, “the Friend and Helper,” is a strange scene, and it does indeed mark a “sudden change of tone.” The reader does not expect to discover, in the midst of this paean to friendship and domesticity, a glimpse of something far greater than friendship or domesticity — something good beyond Badger’s goodness and yet infinitely more frightening — something numinous. Failure or not, the scene was recognized as central by the book’s first publisher, Methuen: The cover features a gilt engraving of Pan, with Mole and Rat below and to either side of him. (A begoggled Toad looks confidently out at us from the spine. Interestingly, as Lerer points out, Toad stands up straight on two very human legs, while Ratty and Mole are rendered simply as animals.)

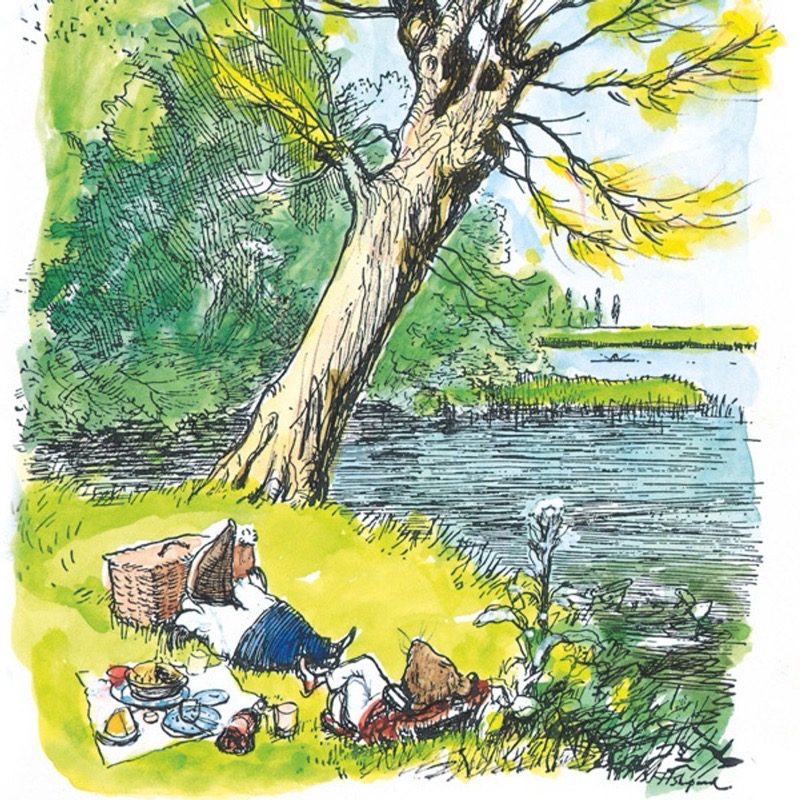

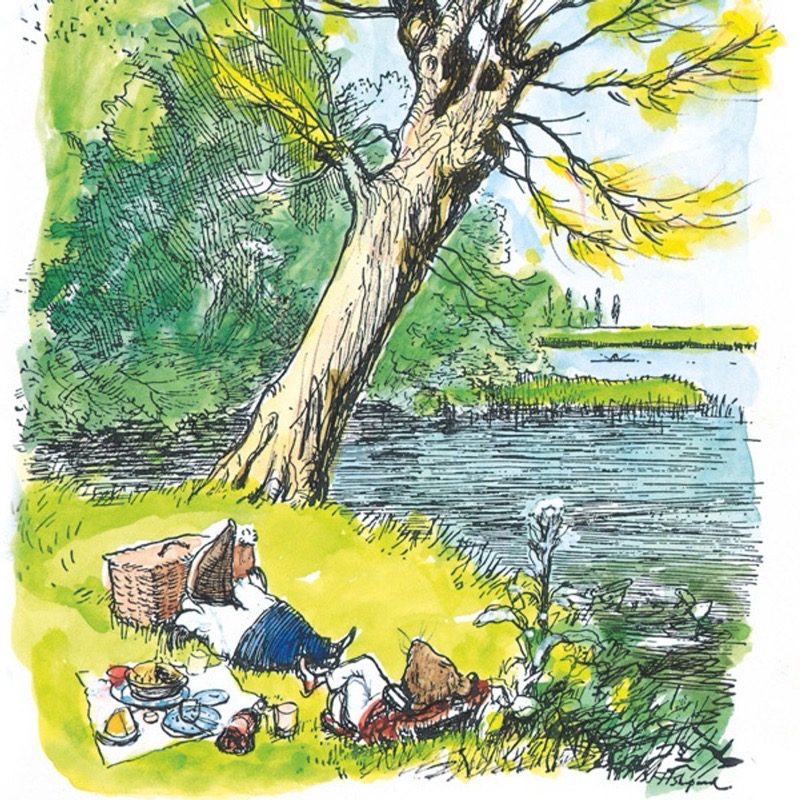

The best illustrator of this scene, I think, is Michael Hague. His portrayal stretches across two pages, and the flora surrounding the figures are painstakingly rendered: It is only on a second or third look that one discerns tiny Portly at Pan’s feet. Among the many who have drawn or painted The Wind in the Willows, Hague and Arthur Rackham are best, I think, at the more expansive scenes, and no one does the details of English domesticity as well as Hague. (His illustrations of The Hobbit are notable in this respect as well.) But for Ratty and Mole on the river, or enjoying their sun-illumined picnics, I must have Ernest Shepard, best known as the illustrator of A.A. Milne’s Pooh stories. He catches the joy of the friends, their unadulterated blissful delight in the shape of their little world, as no one else does.

Perhaps there is a reason for that. Kenneth Grahame was an old man when Shepard was commissioned to illustrate his book — indeed he did not live to see the finished product. But when he spoke to Shepard at the outset of the project, he made a simple request. “I love those little people,” he said. “Be kind to them.”

And now, for me, it’s back to a reading of the story that I wish I had known in my childhood. (And yet would I have loved it then?) The river holds more than enough excitement, after all, and so does The Wind in the Willows. When Mole asks Ratty about the Wild Wood, he receives just a few broken, reluctant, uninformative sentences. And when he asks about what might be found on the other side of the Wild Wood, he gets only this quite proper rebuke: “‘Beyond the Wild Wood comes the Wide World,’ said the Rat. ‘And that’s something that doesn’t matter, either to you or me. I’ve never been there, and I’m never going, nor you either, if you’ve got any sense at all. Don’t ever refer to it again, please.’”