I love this idea from my buddy Austin Kleon: not listing but rather mapping the books you’ve recently read. I have never thought of this but am convinced that I need to try.

Stagger onward rejoicing

I love this idea from my buddy Austin Kleon: not listing but rather mapping the books you’ve recently read. I have never thought of this but am convinced that I need to try.

In David Thomson’s The Big Screen, largely a history of movies, there’s a chapter on television that contains a sentence, a simple and straightforward sentence that’s nonetheless worthy of serious and extended reflection: “This book is not interrupted every sixteen pages by a cluster of advertisements.”

The older I get, the more common this experience becomes: finding that I am simply unable to read essays and articles on certain topics. I may, out of a sense of duty, begin to read something on these topics, but almost immediately my eyes begin to wander, or to glaze over. I strive to refocus; I re-read the same few sentences; but before long my mind has wandered elsewhere. Eventually I give up.

I used to be able to read about some of these things, but the way The Discourse asymptotically approaches the point of absolute stupidity — a stupidity than which no stupider can be conceived — has now rendered my brain dysfunctional w/r/t the following:

That is of course only a partial list, but it seems to cover about 90% of what I’m seeing in news periodicals these days.

One nice feature of Feedbin is the ability to create actions based on filters. So, for instance, I have just created an action to set any new article that contains the word “abortion” as read; that way it won’t show up in my “unread” feed, which is the only feed I look at. A couple of weeks ago I created a similar action for the term “Elon Musk”; I had already targeted posts that have “Burnout” or “Productivity” in their titles — if the Bad Words are not in the actual title then maybe their use in the text is innocuous. We’ll see how it goes; I’ll adjust as necessary. Keeping my sanity requires constant vigilance — unless I want to go offline altogether, which, believe me, I often consider.

On the other side, things I find that I want to read more about these days:

Mainly, though, I want to read more novels.

[I thought I had this post scheduled to go out tomorrow, but obviously I messed up. Consider this, then, a proleptic disclosure of the eschaton.]

Three brief thoughts on this:

An excellent post by John Siracusa (a) outlining the most elementary features that the UI of any video-streaming service should have and (b) showing how rarely (if ever) the existing services meet that low bar. This is something that I think about almost every day: How absolutely incompetent the coding is of the streaming services I use. And in my experience music services are almost as bad.

(Apple’s purchase of Primephonic last year gave me a tiny bit of hope that I’d eventually have an app that allows me to listen to classical music without, for instance, having to deal with truncated and hence incomprehensible track listings for classical music — but I’m still waiting for Apple’s version of the service to be released, and am not confident that it ever will be.)

More generally, it seems to me that UI design in software has been getting worse over the past decade, and I wonder why that is. For instance, Amazon’s Kindle software, on every platform, is buggy, and seems increasingly to be focused more on trying to sell me books than on making my reading experience a good one. Yet another reason — there are several — why I’ve almost completely stopped buying Kindle books, though I still use the device for reading, e.g., Project Gutenberg books. But confusing or inappropriate UI design is not solely the province of Amazon — it seems to be becoming endemic. That’s impressionistic and anecdotal, to be sure; if I weren’t preoccupied by other things I’d try to support my claim. But hey, just read Siracusa’s excellent post.

Stefan Collini’s review of Claire Tomalin’s book on H. G. Wells is very strange indeed. For one thing, he only mentions the book under review in the final paragraph. But more odd still is the refrain with which he begins and ends the review: “It can be hard, from this distance, to see what all the fuss was about,” he says in the first sentence; and then he concludes, “Tomalin is a weighty advocate, and her admiration may help to spark a revival in Wells’s reputation, though perhaps even her noted empathy and artistry still cannot quite re-create for us, now, what all the fuss was about.”

I can easily understand a reader today not thinking highly of Wells’s fiction. But if you can read The Time Machine and The War of the Worlds and Tono-Bungay and Ann Veronica and fail “to see what all the fuss was about,” I don’t know what to say to you. Wells’s fiction touches on most of the major themes and concerns of British culture in his lifetime, and a failure to grasp this is a failure of readerly and historical imagination. You don’t have to think him a great writer to see that he was a ceaselessly dynamic and provocative figure, even if his ever-more-pompous predictions, warnings, and commandments ended up making him look somewhat ludicrous (as in the caricature of him as Horace Jules in C. S. Lewis’s That Hideous Strength).

I haven’t read Tomalin’s book — devoted just to the first half of Welles’s career — but I have read Adam Roberts’s “literary life” of Wells, which masterfully puts all of Wells’s voluminous writing into proper context. I’ll leave you with a passage from that book:

As the world has grown bigger and more complex, as well as more complexly interconnected, a kind of socio-technological sublime increasingly threatens to overwhelm our individual subjectivities like Hokusai’s great wave. Steampunk is, inter alia, an attempt to dress technological advance in the habiliments of a more elegant and refined age, and Wells is one of the ways of focalising that. More, this cultural representation — the boyishly mobile and inventive Wells, the Wells of diverting scientific romances and sexual liberation — speaks, in part, to an ill-focused desire to assert ‘the little man’ (less so ‘the little woman’) in the teeth of this intimidating vastness. There is enough of Wells actual life-trajectory in this to give it bite: the physically small individual from small-scale roots who created himself as a world-class writer and thinker. He takes his place alongside other pervasive cultural myths of the small-man who effects great things in a baffling and alarming world — heroic hobbits, magical schoolboys: contemporary iterations of a fundamentally infantalising legendarium of underdoggishness. One need not deprecate these contemporary myths, any more than one need look down on Wells’s extraordinary achievements in the field of science fiction, to think this sells his larger achievement short. If there has been one through-line in the present work it has been that Wells was a literary artist of immense, underappreciated talent, a writer whose literary genius, whilst it must of course be central to a literary biography, deserves to be resurrected in a much broader cultural context too.

Reading Weinstein and Montás, you might conclude that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth. Take my word for it, we are not. We are not better or worse than anyone else. I have read and taught hundreds of books, including most of the books in the Columbia Core. I teach a great-books course now. I like my job, and I think I understand many things that are important to me much better than I did when I was seventeen. But I don’t think I’m a better person.

Sure, but have you tried to be?

I don’t want to be too flippant here. I have myself, many times, argued against the claim that reading great books is intrinsically ennobling. My argument has been that how we read — with whom, and with what purposes in mind — matters more than what we read. But I think it’s both possible and desirable for students and teachers to read and study together in search of wisdom. And that’s largely what Montás and Weinstein argue for. I do think they are a rather too reverent about the books officially designated as Great, rather too confident in the value of mere exposure to such books. Still, the purposes of education, of teaching and learning, are their chief theme.

They also — Menand complains about this at length — say that in the modern university the practices of reading associated with those true purposes of education are either marginalized or forbidden. Menand actually quotes Montás’s argument that “Too often professional practitioners of liberal education — professors and college administrators — have corrupted their activity by subordinating the fundamental goals of education to specialized academic pursuits that only have meaning within their own institutional and career aspirations.” But isn’t it pretty obvious that someone who thinks this will not, indeed cannot, also think “that English professors, having spent their entire lives reading and discussing works of literature, must be the wisest and most humane people on earth”?

Menand is so transparently impatient with the arguments of Montás and Weinstein that he gets similarly confused at several points in his essay. For instance, to Montás’s claim that Nietzsche is “Satan’s most acute theologian,” Menand replied that “Nietzsche wanted to free people to embrace life, not to send them to Hell. He didn’t believe in Hell. Or theology” — or, presumably, Satan. But maybe Montás believes in Satan, which would, surely, be the point.

Let’s try to focus on the key issue here: Both authors under review couldn’t be clearer that their main argument is not that we should all be reading great books but that we should be reading great books in light of what they believe to be “the fundamental goals of education.” So the proper question to ask is not, “Will reading great literature make me a better person?” The proper question is, “Will reading great literature in company with others who are in search of self-knowledge, meaning, and wisdom make me a better person?” (Answer: Maybe not. And not automatically. But it does give you certain opportunities for becoming wiser if in a disciplined way you choose to take them.)

Why does Menand teach in a university? I read his essay three times looking for evidence, and the only thing I find is this: “The university is a secular institution, and scientific research — more broadly, the production of new knowledge — is what it was designed for.” (He sets this in opposition to the argument of the writers he review that it’s vital to read for self-knowledge.) He says that “Humanists … should not be fighting a war against science. They should be defending their role in the knowledge business.”

With this point I’m in complete agreement. Wissenschaft should not be simply dismissed in favor of Bildung, and there can be real Wissenschaft in the humanities (though I’m not sure many of the critics and theorists Menand defends are interested in either educational tradition). I agree with Tom Stoppard’s A. E. Housman, in The Invention of Love:

A scholar’s business is to add to what is known. That is all. But it is capable of giving the very greatest satisfaction, because knowledge is good. It does not have to look good or even sound good or even do good. It is good just by being knowledge. And the only thing that makes it knowledge is that it is true. You can’t have too much of it and there is no little too little to be worth having. There is truth and falsehood in a comma.

Among my own writing and works, the ones I am proudest of are the ones — like my Auden editions — in which I am clearly if in a small way adding to our store of knowledge.

So two cheers, at least, for Wissenschaft. The chief point I’m wanting to make here is simply this: There’s something rather peculiar about a scholar who proudly disavows using professional teaching and study for personal moral formation and then says, as though he’s clinching a point, that his professional teaching and study have not contributed to his personal moral formation.

I have decided that I want 2022 to be a Year of Re-Reading — it would be rash for me to say that I won’t read any new books, but I really want to focus on returning to books that I want to know better. (I realized some years ago that I don’t really know the value and use of a book until I read it three times.)

But I decided, before the new regimen begins, to read Our Mutual Friend — one of the three Dickens novels (the other two being The Old Curiosity Shop and Martin Chuzzlewit) that I had never read. Having now completed it, I find that it’s one of the most complex and profound of Dickens’s novels but also surely the least enjoyable.

I was therefore taken aback when I saw what Chesterton said about it:

Our Mutual Friend marks a happy return to the earlier manner of Dickens at the end of Dickens’s life. One might call it a sort of Indian summer of his farce. Those who most truly love Dickens love the earlier Dickens; and any return to his farce must be welcomed, like a young man come back from the dead.

Did he read the same book I read? “Farce”? The humor in this book — and there is of course a lot of it — is not farcical but savage. Insofar as the book marks a return to an earlier Dickens, it’s not a happy-go-lucky farceur but rather a bitterly angry social critic. Peter Ackroyd, in his great biography of Dickens — one of the finest biographies I have ever read — gets this right:

In fact this is the first novel in which he directly confronts and attacks contemporary English social behaviour (Little Dorrit had been much more concerned with its institutions and its bureaucracy), all the marriages, arranged or otherwise, all the dinner parties and Commons business now seeming quite false and unreal, in a world of morbid vacancy, stale routines and universal hypocrisy. Social events are depicted as occasions of torment and even the act of eating and drinking in company, so joyful a social ritual in Dickens’s earlier novels, is now seen as no more than another twist of the knife. And the gossip, the dreadful gossip, the gossip of which Dickens was so often the subject and which he truly feared and hated, is also anatomised. There is here, then, a general hatred for society; a hatred which he had as a child and young man but which now returns in a savage attack upon the world in which he lived and moved and of which he was, indeed, a principal ornament. That is why his sympathies in Our Mutual Friend lie with the odd and the outcast; those who, as it were, are forced to clean up and live off the waste and detritus of the rich (such large dust heaps, in reality dominating the landscape of Battle Bridge and Liverpool Street!). And perhaps that is also why, in the figure of the distressed Betty Higden running from the spectre of the workhouse, he returns to the attack he had made upon the New Poor Laws twenty-seven years before in Oliver Twist. All the radicalism of his youth is returning again, in his last finished novel.

And:

If this was a man who could glance once at a row of shops and remember the details of every one, how could he do otherwise than instantaneously recognise and understand the contemporary life around him? Not just the filth and wretchedness which persisted in London through the years of reconstruction — Hippolyte Taine said of Shadwell in this decade, “I have seen the lower quarters of Marseilles, Antwerp and Paris: they come nowhere near this.” But Dickens sensed and recognised something else as well; he sensed in the change of London a change in the nature of civilisation itself. A civilisation that he anatomised in Our Mutual Friend with the Veneerings and the Podsnaps. Speculation. Peculation. Overseas investment. Short-term money markets. Brokering. Joint stock banking. Discount companies. Limited liability. Credit. A world in which human identity was seen in terms of monetary value. A world of barter and exchange. And thus, in the houses of the middle-class and upper middle-class, the fake “marbling”. Veneer. Imitation wood. Chinoiserie. Exaggerated ornamentation. Blankets of fabric. Stifled silent rooms. Death. Gold. Filth. This is the world of his last completed novel.

What a troubling book. You laugh, but you laugh uneasily; you laugh to keep from raging. It’s a brilliant performance but one that I admire far more than I enjoy — as, I am sure, Dickens intended.

I think maybe it’s an especially apt book for our own moment. It does much of what what John Lanchester tried to do in his novel Capital but didn’t have the bitterness to pull off.

And with that … Happy New Year! A toast: Good health to local cultures and confusion to surveillance capitalism!

Many academics are far too sophisticated to take seriously the thought that literature is a special form of intimacy. Academic discourse tends to think of literature in impersonal, collective terms, typically as something that almost everyone, it seems, calls ‘cultural production’. It is of course true that works of literature are artefacts of cultural production, but true in the same trivial way that persons are artefacts of genetic production. It omits everything that makes a work interesting in itself, everything that makes it matter. The whole idea of literature as impersonal production rather than as a form of intimacy seems intellectually self-defeating.

It is not that the documentary hypothesis is necessarily wrong in substance; Genesis is clearly made up of a number of traditions which have been combined at different stages. But is it not the task of the critic to try and come to grips with the final form as we have it, and to give the final editor or reactor the benefit of the doubt, rather than to delve behind his work to what was there before? The inventors of the documentary hypothesis believed that by trying to distinguish the various strands they were getting closer to the truth, which, in good nineteenth-century fashion, they assumed to be connected with origins. But in practice the contrary seems to have taken place. For their methodology was necessarily self-fulfilling: deciding in advance what the Jahwist or the Deuteronomist should have written, they then called whatever did not fit this view an interpolation. But this leads, as all good readers know, to the death of reading; for a book will never draw me out of myself if I only accept as belonging to it what I have I already decreed should be there.

— Gabriel Josipovici, The Book of God (1988)

It’s cool when a friend publishes a new book:

And even cooler when that book contains a chapter on another friend’s work:

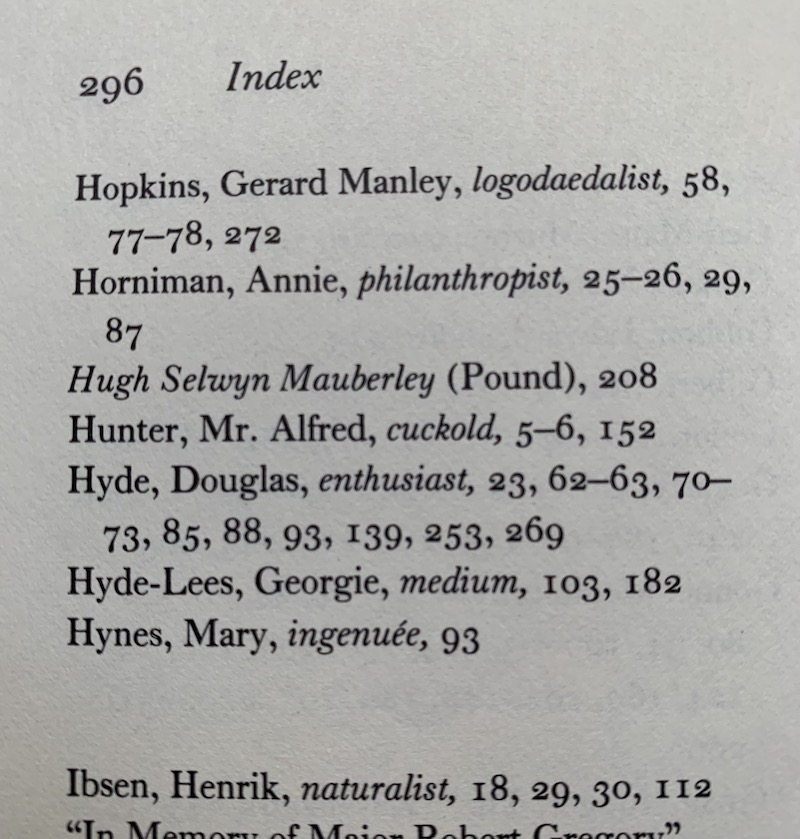

Lots of enjoyable coverage of Dennis Duncan’s new and wonderfully titled Index, A History of the. (You may find a brief excerpt from it as a work-in-progress here.)

The best thing I’ve seen is (unsurprisingly) by Anthony Grafton in the LRB. Here’s a noteworthy passage:

Indexing flowered at a time when readers saw books as great mosaics of useful tags and examples that they could collect and organise for themselves. The chief tool they used to do this job was not the index but the commonplace book: a notebook, preferably organised by subject headings known as loci communes (common places), which provided both a material space in which to store material and a set of designators to help retrieve it. Like indexes, commonplace books were wildly popular. John Foxe, a corrector of the press during his exile years in Switzerland, printed two editions of a blank commonplace book designed to be filled in by users under Foxe’s various headings. One such user, Sir Julius Caesar, crammed his copy so full of notes and excerpts that the British Library classifies it as a manuscript. In his preface to the first edition, Foxe made clear that he knew he was riding a wave. He worked for Johannes Oporinus, the Basel printer who brought out the Magdeburg Centuries, a vast Protestant history built on commonplace books compiled by students. Foxe pointed out, with relish, that everyone who was anyone was making commonplace books and telling others how to do so. Humanists commonplaced to ready themselves for effective speech and writing, medical men, lawyers and theologians to prepare for their professions. Foxe argued that the commonplace book was vastly superior to the index. The index might point you to the materials you need, but the commonplace book actually provided them, handily organised. Holmes, like his contemporary Aby Warburg (another dab hand with scissors and paste), was a late master of the commonplace book, even if he called it an index. If printing made indexes easy to compile, commonplacing made them indispensable to printers and readers alike.

In response to the TLS’s review, my dear friend Tim Larsen wrote in with the following:

I can confirm that one does indeed need a human indexer with a decent knowledge of the topic at hand. I thought I could safely ignore the index for my Oxford Handbook of Christmas (2020), but when it came back with an entry on “Joseph, father of Jesus,” I knew I had to step in. Mercifully, it went to press as “Joseph, husband of Mary.” As to humour in indexes, one of my favourites is E. P. Sanders’s Paul and Palestinian Judaism (1977). Its index has an entry for “Truth, ultimate.” The three pages listed under it lead one to the blank pages that divide the book’s parts.

Let me register a vote for My Favorite Indexer: Hugh Kenner. In some of his books he not only tabulated references to key figures, he offered memorable single-word descriptions of many of them. A few examples from his book on Irish writers, A Colder Eye:

Of course, the delight here is turning to the appropriate pages to find out just how Kenner settled on the identifications he chose.

This Ian Bogost essay on e-books is an oddity, in the sense that about a decade ago we had thousands of essays on this same theme, but have had very few since. That, I think, is because everything got hashed out back then as thoroughly as it is likely ever to be. I am not sure what Bogost’s essay adds to that long-ago conversation, but I know the chief thing it neglects: eyesight. Many people who love codex books (myself included) read e-books when the combination of poor eyesight and poor book design makes reading a given codex painful or even impossible.

This lovely post by my friend Wesley Hill on carrying and using a Bible reminds me of a question I ask myself on a regular basis: What is Christianity when it is no longer a religion of the book? Because I think Christianity around the world, for varying reasons, is becoming and in some places has already fully become a post-book practice. I don’t think we Christians have reckoned as seriously as we ought to with that change — and especially how those of us who remain People of the Book are best to relate to and connect with those whose Christian faith doesn’t employ books.

This is a follow-up to my recent post on not reading the Bible. There I quoted Heidegger on the “hermeneutic circle,” and while I think what is has to say is extremely important for every would-be reader of the Bible, his image can in certain respects be misleading or troubling — because to some anyway it suggests fruitlessness, not getting anywhere, a hamster running in its wheel. I don’t think that’s what Heidegger meant to convey, so let’s try a slightly different image that might capture the key point.

“Prayer I” might be George Herbert’s most famous poem. Every phrase in it is worthy of reflection, but I want to focus on three words from the penultimate line: “the soul’s blood.”

We don’t know precisely when “Prayer I” was written, but I suspect that it was after 1628, which is when William Harvey published his landmark work on the circulation of the blood, Exercitatio Anatomica de Motu Cordis et Sanguinis in Animalibus. That is, I think that Herbert is elaborating an analogy: As blood is to the body, so prayer is to the soul. Prayer then is a circulation. I think we see something like this in the Bible, in which prayer is figured both as our knocking on God’s door (Luke 18) and God knocking on ours (Revelation 3): a back and forth that can be initiated by either party. God calls Abraham and Paul; Job and Jeremiah cry out to God. Call and response; question and answer.

It’s in this sense that reading the Bible is, ideally, circular.

(I’ll keep coming back to the issues I’ve raised, but probably in small reflections like this one. Attempting to piece together some thoughts, one fragment at a time.)

The title of this post is the title of a book I have, for about twenty years now, thought of writing. My thesis would simply be this: We can do almost anything with the Bible except read it.

It is also true that the Bible, especially the Old Testament, tends to resist interpretation — Erich Auerbach famously illustrates this in his discourse on the story of the binding of Isaac in the first chapter of Mimesis — but that’s not what I am talking about here. But I haven’t yet written the book because I find it difficult to explain precisely what I am talking about.

The Bible has a distinctively protean character; it’s a shape-shifter. That is the result, I think, of its being a book that is also a set of books (books that are themselves often stitched together in peculiar ways). Faced with this shape-shifting, we have a tendency to stand away from it to try to see it whole — at the cost of rendering the details invisible — or to zoom in on the details in a way that causes us to lose sight of the greater narrative arc. The former tendency produces books like Northrop Frye’s The Great Code; the latter tendency leads to people receiving Bible verses as text messages.

I think readers of the Bible are always pulled in both of these directions. We may think that in our moment — the moment of text-messaging and the child of text-messaging, Twitter — we are especially prone to fragmenting the biblical text, but let’s recall that when the Bible was first divided into verses — by Robert Estienne in the mid-16th century — one of the most popular books in Europe was Erasmus’s Adagia. Adages or proverbs then, texts now — the impulse to reduction and condensation is the same.

I don’t think we can address this difficulty by assuming and maintaining some kind of ideal middle distance. That proposed solution arises from the twin assumptions that the protean character of Scripture can and should be arrested. But what if neither of those assumptions is correct? What if the only way genuinely to read Scripture is to engage in a constant zooming in and zooming out?

This model of reading resembles the famous “hermeneutic circle” — understanding the whole in terms of the parts and the parts in terms of (our assumptions about) the whole — but reading and interpretation are not the same thing, even if they are often related.

Heidegger’s famous essay “On the Origin of the Work of Art” — an essay he revised repeatedly, which should tell us something about both the importance and difficulty of the issues involved — describes a version of the hermeneutic circle. In this case, though, he is not discussing the relationship between part and whole but between a work of art and the very concept of “art.”

What art is we should be able to gather from the work. What the work is we can only find out from the nature of art. It is easy to see that we are moving in a circle. The usual understanding demands that this circle be avoided as an offense against logic. It is said that what art is may be gathered from a comparative study of available artworks. But how can we be certain that such a study is really based on artworks unless we know beforehand what art is? Yet the nature of art can as little be derived from higher concepts as from a collection of characteristics of existing artworks. For such a derivation, too, already has in view just those determinations which are sufficient to ensure that what we are offering as works of art are what we already take to be such. The collecting of characteristics from what exists, however, and the derivation from fundamental principles are impossible in exactly the same way and, where practiced, are a self-delusion.

So we must move in a circle. This is neither ad hoc nor deficient. To enter upon this path is the strength, and to remain on it the feast of thought — assuming that thinking is a craft. Not only is the main step from work to art, like the step from art to work, a circle, but every individual step that we attempt circles within this circle.

I want to think about this passage and return to it later, because I believe it has implications not just for understanding what art is, not just for clarifying the nature of interpretation, but for helping us to read, even read the Bible.

As Eve Tushnet has reminded us, “Mercy to the guilty is the only kind of mercy there is,” which is something to remember as you read about Shirley Chisholm and George Wallace.

This Stefani McDade report in Christianity Today about the post-Trump reckoning among charismatic Christian leaders is absolutely superb.

I am so pleased to be named (by my dear friend Richard Gibson) among my people, the idiosyncratic readers.

Re: this reflection on printed books: for the last decade, e-books have comprised about 10% of the sales of my books, and that’s been pretty constant.

Zito Madu, speaking strong and bitter truth:

The feeling of dread before Saka took his penalty betrayed a truth about the relationship between the Black English players and members of their country. The wish for Saka to score in order to avoid racist abuse only reveals a deeper truth: that respect for him as a person and recognition of his dignity is only possible if he and the other Black players keep making the people who hate them happy. A conditional respect of a person’s humanity, which means that it’s no recognition at all. […]

It was heartening to see some fans, teams and politicians push back against the bigotry by showering the players with love and support. A group of people decorated the defaced Rashford mural with hearts. Yet, while the players surely appreciate the support, and hopefully will one day have a chance to have success at the highest level, it’s not hard to imagine that they will never forget that many of their supporters see them as sub-human — and no level of sporting achievement will change that.

Auden used to say that he had a kind of guardian angel who was always there to tell him what to read next. I sometimes I think I have one too, though my angel is rather less consistently attentive than Auden’s was. But she has one habit I like: she tells me when not to read something. Yes, you’ll want to read that, she whispers, but wait. Wait a while. Not now, but later.

One book she told me to delay the reading of is Robin Sloan’s novel Sourdough — but recently she gave me permission, and I eagerly, um, devoured it. What an absolutely delightful tale! I recommend it to you all, as soon as your reading angel — you have one, I trust — gives you the O.K.

One of the great things about Sourdough is that it’s an utterly charming story that opens up, at the end, towards a future that could be quite utopian … or, marginal chance, quite dystopian.

Very few sites on the internet are meant to facilitate reading — most are, in fact, designed to inhibit reading. Imagine watching a movie and having the image regularly shrink to a tiny size, overwhelmed by a much larger advertisement which also plays its sound at double the volume of the movie’s sound — that’s what reading a corporate site is usually like. (I hope you will have noticed that I try to make this blog easily readable on large and small screens alike. Also, perhaps, that I have recently added a button to enable dark mode.)

So what to do? Well, most browsers now offer some kind of reading mode, which helps a lot — though I have not found one that works on every site. Or you could use a read-it-later service like Instapaper or Pocket. I do these things.

Sometimes, though, I come across a long story or article or essay that I want to read without any of the distractions of being online. In that case I choose one of the following options:

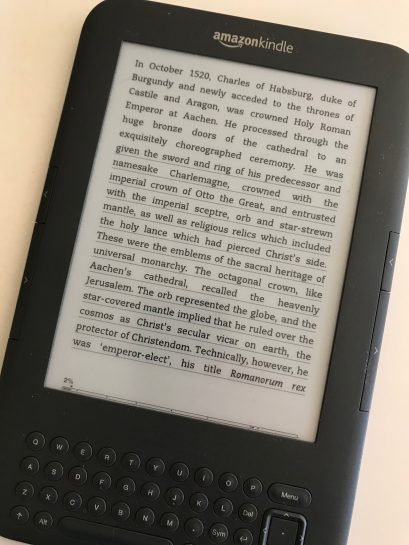

(1) If simply attentive reading is the goal, I often use a service called Push to Kindle. It does a superb job of converting webpages so that they’re perfectly formatted for the Kindle. For instance, someone recently recommended to me a long SF story called “Folding Beijing” — that’s a perfect candidate for Push to Kindle. I downloaded it and will probably read it in the next day or two. When anything is over 2500 words or so I get really uncomfortable reading it on my computer, so I often use this service for the lengthy reviews in the London Review of Books — to which I subscribe, but the print in the paper edition is uncomfortably small for my aging eyes — and their extended analytical essays like Perry Anderson’s three recent reflections on the European Union — totaling 45,000 words, longer than my most recent book — are also best-suited for the Kindle.

(I’m trying not to buy anything else from Amazon, but I continue to use what I’ve already bought, putting off the Day of Decision until my current Kindle dies.)

(2) But if I need to interact significantly with the text — highlight and underline — then I use a different service, Print Friendly. It converts webpages to PDFs that can be saved and/or printed. I use this all the time when I want to make PDFs to send to my students, or when a post really demands critical attention. Example: Ada Palmer’s long post from last year on the ways in which the Renaissance was worse than the Middle Ages.

There’s a lot of great stuff on the internet. Not much of it is presented in ways designed for serious reading. But as you can see, that’s a problem that can be addressed.

College students are busy, so they practice triage: they decide (a) what must be done now, (b) what can wait until later, and (c) what need not be done at all. If a professor tells students to do something but offers no reward for doing it and no punishment for failing to do it, then it will inevitably go directly into category (c).

This is why I give reading quizzes — a common enough practice. But over the years I have come to build my entire classroom practice around those reading quizzes. My method looks like this:

My notes for the class will typically look like this — from Claude Levi-Strauss’s Tristes Tropiques, which I just finished teaching in one of my classes. (It’s one of my favorite books to teach.) When I make up the quizzes I keep a copy for myself and annotate it, as you can see, so I can not only point to the pages where the answers may be found but also identify other key passages, many of them related, thematically, to the ones I asked the questions about.

Books I teach tend to look like this:

And there are many notes on the inside. I’m thinking that when I retire I should bundle a much-taught book with its annotated quizzes and sell the bundle as my own version of an NFT.

Let’s be clear: Ryan T. Anderson’s book When Harry Became Sally has not been banned, and there are no “free speech” issues involved here. (Not in any precise sense, though I may say more about this in another post.) A retailer has decided not to sell a product. But because the retailer involved is Amazon, and Amazon has such an outsize influence over the book market, it seems to me that every published author ought to worry about what might happen to their sales if they got on Amazon’s bad side.

A number of interesting and important issues converge on this decision. For instance, the fact that by removing the book with no warning, no explanation, and no opportunity for appeal, Amazon is violating its own publicly announced guidelines: “If we remove a title, we let the author, publisher, or selling partner know and they can appeal our decision.” Or the fact that for a couple of days any search for Anderson’s book yielded a result for a book critical of Anderson’s that Amazon would clearly prefer you to read. (That now seems to have been replaced with a standard 404 page.) Or the apparent fact that there are no other topics of current dispute on which dissent is absolutely prohibited: for instance, you can still purchase Pluckrose and Lindsay on critical theory and Douglas Murray contra identity politics — for now. Or the fact that Amazon no longer has an email address you can write if you want to protest such a decision.

But to me, the most interesting point for reflection is this: The censors at Amazon clearly believe there is only one reason to read a book. You read a book because you agree with it and want it to confirm what you already believe. Imagine, for instance, a transgender activist who wants to understand the position held by Ryan Anderson and people like him in order better to refute it. That person can’t get a copy of the book through Amazon any more than a sympathetic reader like me can.

But another, deeper belief lies beneath that one: It’s that ideas like Anderson’s are not to be refuted but rather, insofar as it lies within Amazon’s vast power, erased — subjected to Damnatio memoriae. And the interesting thing about that practice is that it is simultaneously an assertion of power and a confession of weakness. Amazon is flexing its muscles, but muscles are all it has. Its censors don’t want anyone to read Anderson’s book because they know that they can’t refute it. They have no thoughts, no knowledge — only reflexes. And reflexes will serve their cause. For now.

A reader of my book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction — in which I have some harsh things to say about the eat-your-broccoli approach to reading advocated by Mortimer Adler and Mark van Doren in their famous How to Read a Book — discovers that the professor and literary critic William Lyon Phelps got there many decades before I did:

My take on this is simple: It is better for a good book not to be taught at all than be taught by the people quoted in that article. Yes! — do, please, refuse to teach Shakespeare, Homer, Hawthorne, whoever. Wag your admonitory finger at them. Let them be cast aside, let them be scorned and mocked. Let them be samizdat. Let them be forbidden fruit.

They will find their readers. They always have — long, long before anyone thought to teach them in schools — and they always will.

I normally don’t respond to reviews, either positive or negative, but because I’m getting a good deal of email about this:

I reviewed Alan Jacobs (no longer on twitter alas!)’s new book for @WSJ

My review asks 2 questions:

(1) who is the real audience for a defense of great books?

(2) there’s been a lot of defending: might it not be time for a really vigorous attack?https://t.co/FEHxSFgJVC— Agnes Callard (@AgnesCallard) December 10, 2020

— I’ll make three brief comments.

UPDATE: So now, thanks to this review, I am getting emails from people about my “defense of the classics,” my “advocacy for great books,” and my “defense of the literary canon” — none of which are in any way the subject of my book. (I don’t even mention “the literary canon.”) None of these people have read my book, of course; they’re just assuming that a review in the Wall Street Journal couldn’t possibly have misdescribed the content of the book. I think this must be what Rod Dreher feels like when people who have not read a single word of The Benedict Option opine confidently about their agreement or disagreement with its argument, because of some review or (more likely) some tweet they read. I’m now realizing how blessed I have been over the years that most of the negative reviews of my books have responded to what I actually wrote.

Categories:

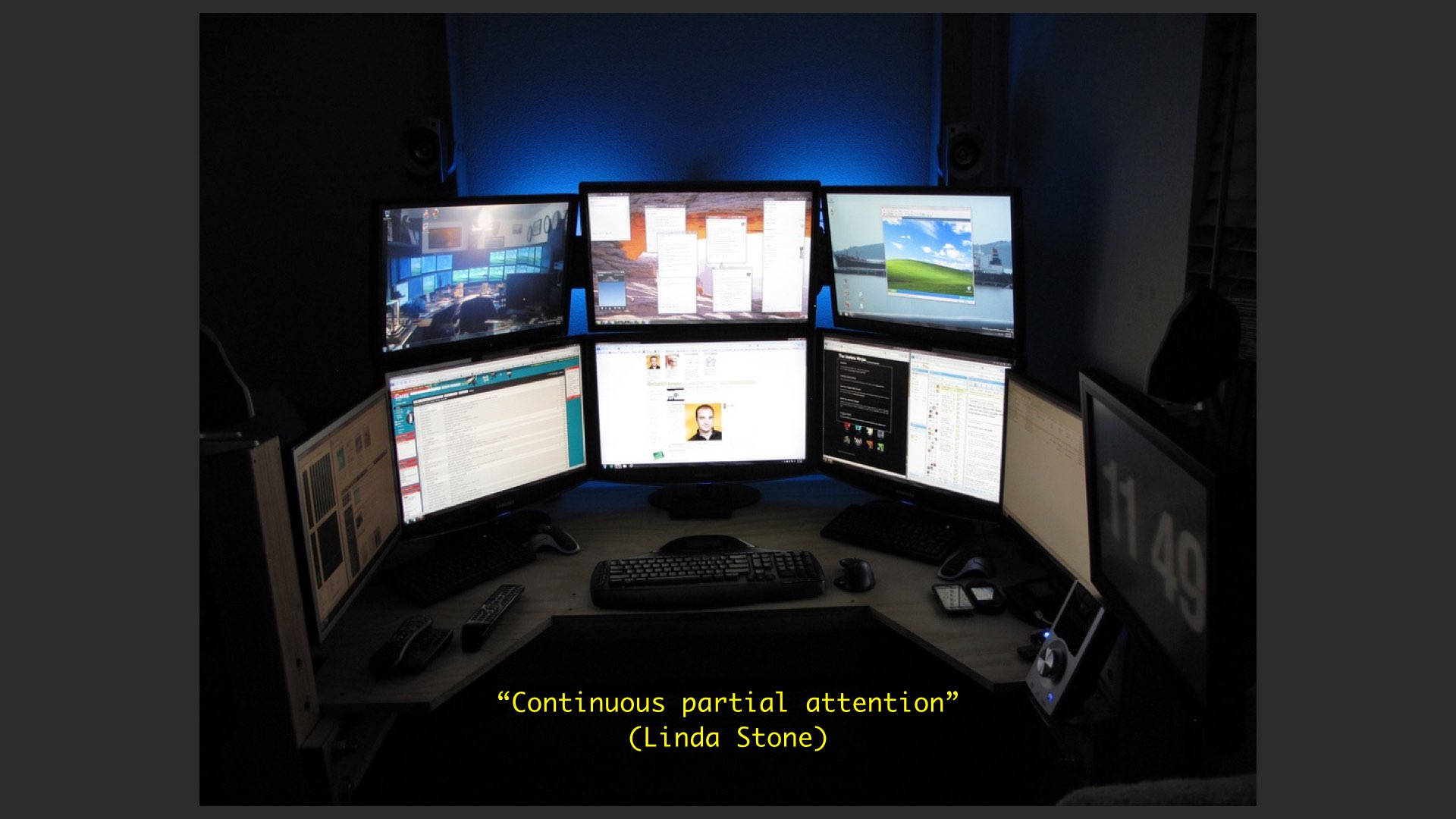

Online is increasingly where people live. My average screen time this past week was close to ten hours a day. Yes, a lot of that is work-related. But the idea that I have any real conscious life outside this virtual portal is delusional. And if you live in such a madhouse all the time, you will become mad. You don’t go down a rabbit-hole; your mind increasingly is the rabbit hole — rewired that way by algorithmic practice. And you cannot get out, unless you fight the algorithms to a draw, or manage to exert superhuman discipline and end social media use altogether. […]

In the past, we might have turned to more reliable media for context and perspective. But the journalists and reporters and editors who are supposed to perform this function are human as well. And they are perhaps the ones most trapped in the social media hellscape. You can read them on Twitter, where they live and and posture and rank themselves, or on their Slack channels, where they gang up on and smear any waverers. They’ve created an insulated world where any small dissent from groupthink is professional death. Watch Fox, CNN or MSNBC, and it’s the same story.

Point out missing facts or context, exercise some independence of judgment, push back against the narrative — and you’ll be first subject to ostracism and denunciation by your newsroom peers, and then, if you persist, you’ll be fired. The press could have been the antidote to the social media trap. Instead they chose to become the profitable pusher of the poison.

This is precisely and tragically correct.

I immediately wrote to Andrew to tell him that he needs my new book, stat. But even Andrew, who writes on a weekly basis, who has stepped back from the moment-by-moment insanity of journalistic Twitter (and from the hour-by-hour insanity of the old Dish), probably doesn’t have time to step back a bit further still over the next few weeks and read some old books.

Or doesn’t believe he has time. Maybe, and maybe for journalists more than for anyone else, this is in fact the perfect, the ideal, the necessary moment to recover “real conscious life outside this virtual portal.” One might begin with the epistles of Horace, a man who in exile from Rome learned to love the countryside. Just a thought.

I’m really glad to learn that The Dish is returning — especially in a form that will allow Andrew to write fewer but longer pieces than he did in the old days, and, I trust, by such means to retain his sanity. The former Dish was pedal-to-the-metal every single day, and even Andrew, the hack than whom no sharper can be conceived, couldn’t over the long term flourish at that pace, either emotionally or intellectually.

A slower-paced Dish of his own is surely the best venue for Andrew, who is the most independent of thinkers and therefore a constant threat to the “safety” of any colleagues whose mental cabinets have just two pigeonholes, Correct people and Evil people. (Apparently at New York most of his colleagues were two-pigeonholers.) I subscribed instantly, and I know I won’t regret it.

But Andrew is not the only thoughtful and unclubbable journalist who’s going indie these days, and that poses a problem for me. In that introductory message I linked to above, Andrew mentions the similar Substack-based endeavors of Jesse Singal and Matt Taibbi, and while I think both of those guy as are superb journalists, if I were to subscribe to their work as well as Andrew’s that would cost me 150 bucks a year. I still might do it — but that’s a lot of coin for three voices.

There’s an economies-of-scale problem here. At a newspaper or magazine, writers share an editorial and technical infrastructure, so costs of production are distributed. Those who go it alone don’t get to benefit from that, and neither do their readers. So the cash outlay for those readers can escalate in a hurry.

On the other hand, it’s nice when the money you send to pay the writer actually pays the writer (minus Substack’s cut, of course). I have long wished that places like the New York Times and Washington Post had tip jars for the good writers — if I subscribed to the damned things I would have to subsidize the clueless, pompous, self-righteous, yappy-dog incompetents who dominate those once-distinguished institutions.

One hand, other hand, one hand, other hand. The work of the subscriber-supported solo practitioner doesn’t get seen by nearly as many people as something on the open web — but maybe that’s a feature rather than a bug! Fewer morons to insult you without reading what you write.

Given the hostility of our major media venues to anything that even resembles thinking, there’s no easy solution to this problem. Perhaps some kind of non-partisan, non-ideological journal of ideas will eventually emerge — Lord knows there are enough tech zillionaires to fund one — but in the meantime what does a reader do? This reader is gonna look for some fat to cut from his media budget and pay one or two more writers.

Stochastic resonance (SR) is a phenomenon where a signal that is normally too weak to be detected by a sensor, can be boosted by adding white noise to the signal, which contains a wide spectrum of frequencies. The frequencies in the white noise corresponding to the original signal’s frequencies will resonate with each other, amplifying the original signal while not amplifying the rest of the white noise (thereby increasing the signal-to-noise ratio which makes the original signal more prominent). Further, the added white noise can be enough to be detectable by the sensor, which can then filter it out to effectively detect the original, previously undetectable signal.

This works for sound and image alike, for example:

SR may help to explain why some people learn better when surrounded by white noise — thus writers who hang out in coffee shops. SR has been identified in the sensory neurobiology of many creatures, but I don’t understand that stuff at all, so please don’t have any illusions about my competence to grasp serious scientific ideas.

I mention all this because I think reading texts from the past — something about which I have written a book — is a way of usefully introducing stochastic resonance into our mental lives. Maybe I’m stretching a metaphor here, but bear with me.

Some people say we live in an age of information overload. Clay Shirky has said that it’s not information overload but rather “filter failure.” A slightly different way to put Shirky’s point is to say that a super-surplus of input makes it difficult for us to discern genuine information, to distinguish signal from noise. We can’t sift and sort and bring order to all the stuff assaulting us.

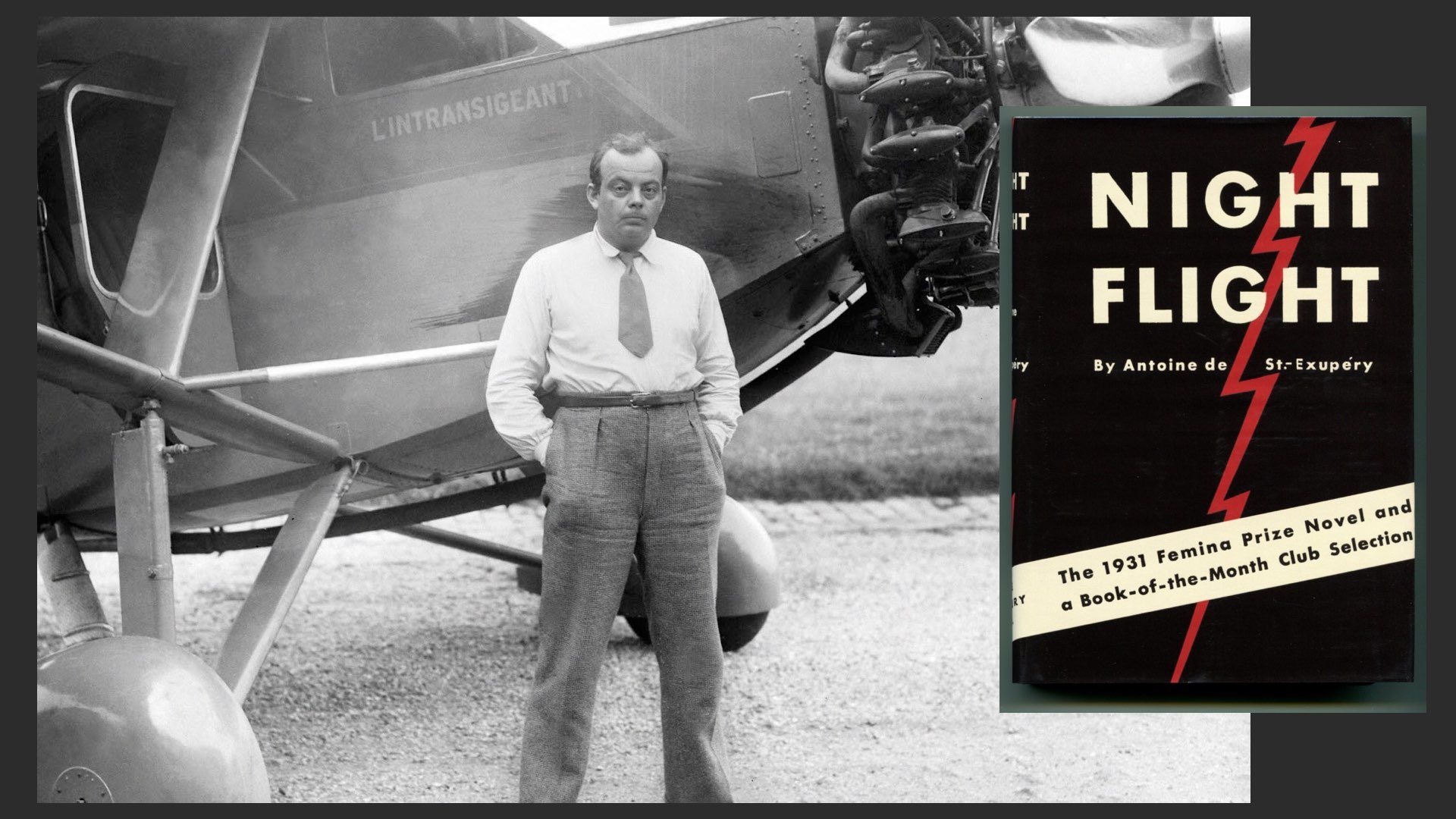

But if you step back from the endless flow of social media and the internet more generally, and sit down with a book from the past that appears to have absolutely nothing to do with the affairs of the moment, something curious and rather wonderful can happen. Unexpectedly and randomly — stochastically — you begin to perceive resonances with your own moment, with the concerns that you may have turned to the past in order to escape.

When you approach the text from the past on its own terms and for its own sake, it becomes a kind of white noise in relation to present concerns. Your attention to the long ago and far away makes the tumult and the shouting die, the captains and the kings depart. (Allusion alert!) It’s when the current environment lies outside the scope of your attention, when you neither seek nor expect any connection to it, that you make room for random resonances to form.

And when they do form, you begin to discern the really key features of your moment more clearly. An image begins to appear where there had been formlessness. Useless and pernicious statements start to recede into the background as you perceive them for what they are. The salient and the helpful points move to the forefront of your attention.

You can’t force this to happen — indeed, any attempt to force it will result in the simple confirmation of what you already think. It’s only when the resonances feel truly random — when they arise at moments when you’re not looking for or expecting them — that they have the power of clarification. You can predict that resonances will occur; but you can’t predict when they’ll show up or what they’ll be.

This may be a subset of the Eureka phenomenon, but at the moment I’m inclined to think that it’s largely distinct from that, though not unrelated.

By the way, I think all that I’ve described here describes equally well the experience of reading much science fiction and fantasy. The fact that almost all of my leisure reading is (a) old books, (b) SF, (c) fantasy suggests that my fundamental orientation as a reader is a hopeful openness to stochastic resonance.

The problem here is the lack of evidence that “deep literacy” really is in decline. Decline from what height? Starting when? Also:

The rise of deep literacy in enough people in early modernity — mightily aided, of course, by Gutenberg’s invention of movable type — was a precondition of Protestantism’s firm establishment and rapid growth, and its establishment was in turn a major accelerator of deep literacy in the societies in which it became the principal faith community, in large part because Protestants ordained compulsory schooling for all children. The Reformation found a very powerful engine in the establishment of these schools: Wherever Protestant beliefs spread, state-mandated education soon followed, each reinforcing the other.

“Protestants ordained compulsory schooling for all children” — all of them? Everywhere? I don’t think so. When and where did this happen? Perhaps Maryanne Wolf provides evidence for these claims in her book, but if so citations of some kind would have been useful. And in any case Wolf is not a historian. Here’s a widely-cited article from 1984 that asks about the relationship between literacy and the Reformation in Germany. The authors conclude that the early Lutherans weren’t especially interested in promoting general literacy — they devoted themselves to promoting catechesis in schools, and this was done orally — and relatively little progress was made in promoting general literacy until the Pietists in the eighteenth century became influential. And even then the achievements were modest:

Besides reorganizing and revitalizing school systems still suffering from the effects of the Thirty Years War, the eighteenth-century ordinances set targets gradually achieved over time. Indicative of the type of incremental progress that was made are some statistics from East Prussia, one of the poorest rural areas in Germany. The percentage of peasants who could sign their names rose from 10 per cent in 1750, to 25 per cent in 1765, to 40 per cent in 1800. Another sign of increasing literacy was the exponential growth in the book trade in the last half of the eighteenth century as the number of titles for sale at the Leipzig book market, the largest in Germany, increased by over 50 per cent between 1740 and 1770 and more than doubled between 1770 and 1800. To be sure, the increase in literacy and reading in the late eighteenth century was still spotty and varied widely in depth and intensity from place to place. Best estimates of school attendance in the second half of the eighteenth century range from one-third to one-half of German school-age children.

How much deep literacy could there be in an environment in which basic literacy was by no means complete — in some areas not even widespread? That’s just in Germany, of course; comparative study needs to be done to make a more general case.

You can’t effectively make an argument like this without being able to answer some questions:

Just to start. And I would ask a deeper and harder-to-answer question: For the overall health of a society, is it the number of people who achieve deep literacy that matters? Or is it the social and political influence of the deeply literate?

One of the first things to go in a time of stress like ours is concentration. We know so little about the coronavirus: whether we will get it and how many people we know will, how serious the disease will be if we do, how long schools and businesses will be closed, the long-term effect on the economy — not to mention the possibility of the virus’s return at some later stage. With all these uncertainties, known unknowns and unknown unknowns, buzzing about in our heads the prospect of sitting down to read a book seems … remote, alien, impossible. And yet all of us could use a vacation from our anxieties, something to occupy our minds. My suggestion: Take some time to read short stories and essays.

Many of the finest short stories ever written are available for free at Project Gutenberg:

And then if you want to turn to essays:

That’s just selecting from the freebies! Maybe I’ll have another post later on things you’d actually need to buy.

Why, you read Prince Kropotkin’s article on Anarchism from the 11th edition of the Encyclopædia Britannica, of course. What else would you do?

Nota bene: This is not a scholarly exercise but rather a readerly one. My students and I are not reading theologians or scholars of the New Testament. We are going so far as to try to forget what we know about the later development of Christianity. (Trying and failing, of course, but that doesn’t make the trying valueless.) We seek to place ourselves imaginatively in the minds of those for whom the Way was an emergent phenomenon. What did Paul’s letters sound like to them?

Now we come to Romans, and what a change. All of our previous readings have been letters in the primary familiar sense of that term, clearly written from a distinct person to distinct other persons, emotionally colored by a highly particular history of experience. Not so this one. The differences are obvious from the opening salutation — dignified, expansive, layered with dependent clauses, adumbrating the themes of the letter as a whole:

Paul, a servant of Jesus Christ, called to be an apostle, set apart for the gospel of God, which he promised beforehand through his prophets in the holy scriptures, the gospel concerning his Son, who was descended from David according to the flesh and was declared to be Son of God with power according to the spirit of holiness by resurrection from the dead, Jesus Christ our Lord, through whom we have received grace and apostleship to bring about the obedience of faith among all the Gentiles for the sake of his name, including yourselves who are called to belong to Jesus Christ,

To all God’s beloved in Rome, who are called to be saints:

Grace to you and peace from God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ.

There’s no question that this is no hurriedly-dashed-off note, but rather a considered performance, full of oratorical flourishes. We might expect from this not a few notes based on the questions and concerns of a particular local congregation, but rather a highly organized treatise. And indeed that’s just what we get: a semi-systematic exposition of the Gospel as Paul understood it, in a fashion almost denuded of personality, at least as compared to the previous letters.

And as far as Chapter 8. After the glorious heights of that section of the letter — “For I am convinced that neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor rulers, nor things present, nor things to come, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor anything else in all creation, will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” — the tone alters markedly. Paul’s personality asserts itself, and we see flashes of the cranky and anxious man we have come to know from earlier letters. But now it is not “anxiety for all the churches” that afflicts him, but rather for the children of Israel: “I have great sorrow and unceasing anguish in my heart. For I could wish that I myself were accursed and cut off from Christ for the sake of my own people, my kindred according to the flesh.” And what is perhaps even more striking about this section of the letter is how uncertain Paul’s views are: it seems obvious that he has received no clear revelation of the precise relationship of the Lord’s covenant with Israel and the salvation that has been accomplished by Jesus Christ. So in the end he can only say: “O the depth of the riches and wisdom and knowledge of God! How unsearchable are his judgments and how inscrutable his ways!”

This blog has been on hiatus, mainly, but now I’m thinking that I should return from time to time. My classes this term are really enjoyable and I’m learning a lot, but I have an unusually heavy teaching load, and I fear that if I don’t take note of some of the things I’m thinking I’ll forget them. And a blog is a good way to give a responsible account of one’s thoughts. So I’ll be here occasionally with field reports.

A small group of Baylor University Scholars and I are reading the New Testament, in a slightly peculiar fashion. I’ve asked them to read each book not in the canonical order, but in the likely order of composition, and to imagine themselves as followers of the Way, this new faith centered on Jesus of Nazareth, whom we believe to be the Messiah of Israel and the Savior of the whole world. But we don’t know whether we’re doing it right. The Way is quite recent, has spread by word of mouth, and no one account of its essentials meshes perfectly with the others. When someone brings to us a painstakingly-copied letter or narrative from what we believe to be an authoritative source, we pounce on it, we treasure it, we read it with forensic attention. And what do we learn?

We have all been struck by certain matters of tone.

We begin with some of the letters of Paul. He begins hopefully. Most scholars believe that the earliest of Paul’s letters is is his first to the Thessalonians, and while he’s happy to answer some of the Thessalonians’ questions about when Jesus will return, his main concern in this letter is to praise them for their faithfulness in following the Gospel that he taught to them. Maybe at that point in his career he thought that this whole “evangelist to the Gentiles” thing was going to be relatively simple.

But his very next letter, most scholars think, is that to the Galatians, and it radiates utter exasperation. “I am astonished that you are so quickly deserting the one who called you in the grace of Christ and are turning to a different gospel — not that there is another gospel, but there are some who are confusing you and want to pervert the gospel of Christ.” Here we discern a note of high anxiety creeping into Paul’s letters: he can visit and teach the members of a particular church, but once he has departed to teach elsewhere, he has no idea how faithful a given community will be to his instruction. He spends a lot of time reminding the Galatians of his God-given authority, of how he was converted not by human persuasion but by the direct intervention of Christ himself. (“Saul, Saul, why do you persecute me?”) Nevertheless, he notes, the other apostles, the ones who knew Jesus in the flesh, have heard from him and have accepted his apostolic authority. Why do “you foolish Galatians” fail to do so? The self-commendation here is relentless and, to some of us, rather off-putting.

In the next letter, the first to the Corinthians, Paul continues to fret: in this case, about divisions within the community. There are soaring heights of rhetoric in this letter, most famously the great paean to love in chapter 13, and soon afterwards the hopeful looking forward to the resurrection of the dead, but the overall tone is anxious. Paul sees this church beginning to pull apart and from the distance at which he writes to them there is nothing he can do about it. In order to convince them to heed his advice he once again beats the drum of his apostolic authority.

We are accustoming ourselves to this Paul, this stressed and determined man, confident in his own calling but increasingly doubtful that that calling will be recognized by his fellow followers of the Way. There are so many false teachers out there, so many ways to go astray. He is like a shepherd whose sheep are scattering over a vast field.

But then we come to the letter to the Philippians, and it is difficult to imagine a greater contrast to what we have been reading.

For at this point Paul is in prison, and clearly doesn’t think he has much of a chance of getting out again. But instead of leading him to despair, this miserable situation gives him a mysterious peace. He realizes that the Gospel of Jesus Christ is infinitely greater than he is, and that even if he dies it will live and thrive. All of his anxiety passes away, and he can earnestly counsel the members of the assembly at Philippi to “be anxious for nothing”: if they but make their requests known unto God, then the peace of God, which surpasses all understanding, will keep their hearts and minds in Jesus Christ their Lord. There is no self-defense here, no self-commendation, no stress — just the serenity of a man who has resigned himself to his own death, who suspects that his earthly story will soon be over, at which point he will enter the company of his loving Lord.

But Paul is not killed; instead, he is released. And when we come to the second letter to the Corinthians we see that the memory of the peace he gained in prison remains, but his old habits of worry return to gnaw at him. He begins again to defend himself, to assert his authority, but now admits that when he does so he is “speaking as a fool.” He seems to know that the profound gift of peace that he received in prison is slipping from his grasp, but he just can’t help himself. The instinct to self-defend is too strong, even though he knows the absurdity of it, when he thinks about the Corinthians ignoring him and giving their homage to those whom he derisively calls Super-Apostles, Hyper-Apostles (Ὑπερλίαν ἀποστόλων).

But whatever anyone dares to boast of — I am speaking as a fool — I also dare to boast of that. Are they Hebrews? So am I. Are they Israelites? So am I. Are they descendants of Abraham? So am I. Are they ministers of Christ? I am talking like a madman — I am a better one: with far greater labors, far more imprisonments, with countless floggings, and often near death. Five times I have received from the Jews the forty lashes minus one. Three times I was beaten with rods. Once I received a stoning. Three times I was shipwrecked; for a night and a day I was adrift at sea; on frequent journeys, in danger from rivers, danger from bandits, danger from my own people, danger from Gentiles, danger in the city, danger in the wilderness, danger at sea, danger from false brothers and sisters; in toil and hardship, through many a sleepless night, hungry and thirsty, often without food, cold and naked. And, besides other things, I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches.

It’s that last line that really catches me: Paul has had all sorts of afflictions heaped upon him, but what weighs heaviest on him is this: I am under daily pressure because of my anxiety for all the churches. The peace that overwhelmed him in prison when he thought his race was run has evaporated. And maybe this is the strongest sense in which he has become a fool, ἄφρονα, without wisdom: he has forgotten that, great though his responsibility is, the Gospel of Jesus Christ can survive and even thrive without his interventions.

We’re at the copy-editing stage of my next book, so it’s too late to add anything, but goodness, I wish I could squeeze in this from Lucy Ellmann:

Some time ago I pretty much decided to read only books written before the atom bomb was dropped, when everything changed for all life on Earth. The industrial revolution’s bad enough, but nuclear weapons really are party-poopers.

I don’t stick strictly to this policy, but I often find it more rewarding to read what people thought about, and what they did with literature, before we were reduced by war and capitalism to mere monetary units, bomb fodder and password generators. And before the natural world became a depository for plastics and nuclear waste.

Anger and alienation have resulted, and they’re fine subjects, but there are times when you’d like to remember some of the higher points in the history of civilisation as well, and the natural world before we learned to view it all as tainted. The intense humour, innocence, sexiness and play of The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman, for instance – could this have been written after Hiroshima? Could Gargantua and Pantagruel? Don Quixote? Emma? I don’t see how. Thanks to the offences of patriarchy, a lot of the fun has gone out of being human, and I like books that look at life in less constricted ways.

I love this statement because of its provocations — provocations that should be assessed with some care. For one thing, I don’t see that the variety of books has especially diminished since Hiroshima — I mean, Chicken Soup for the Soul and The Shack and a whole bunch of adult coloring books have appeared since the end of that war — and if we’re missing the distinctive (and very funny) kind of “sexiness” in Tristram Shandy I think that has a lot more to do with the sexual revolution and its unanticipated consequences than with the atom bomb.

But the idea that before the industrial revolution, with its accompanying “war and capitalism” and reduction of persons to “mere monetary units,” the natural world was perceived in a radically different way — that’s promising. Though I think the main thing that should be said about pre-modern nature is not that it was untainted but that it was scary as shit. Which is just as much worthy of our interest and reflection.

We could debate such matters all day — and should! Because there’s no question that the past really is another country, though they don’t everything different there. Trying to understand the continuities as well as the discontinuities is what reading books from the past is all about.

Anyway, my book is going to be great on all that stuff. Make sure it’s the only book published in 2020 that you buy in 2020, okay? Otherwise, stick with the old stuff. You’ll be glad you did.

The novelist Hannah Beckerman was asked, “I’m an English lit postgraduate who’s slipped into a reading rut since my final exams – what are some good books to get me back into loving literature?” Here are the first publication dates of the books she recommended:

Also, all of them are written in English and by people from England, Scotland, Ireland, and the USA. The two major temporal outliers (1937 and 1926) are both children’s books, and there are no adults-only (or -primarily) novels from before 2002.

Is it really likely that all the books that might be recommended to someone who wants to “get … back into loving literature” are from our culture, our language, our time? And that none of them are poems or plays?

I’m reading Henry James’s late unfinished novel The Sense of the Past for the book I’m writing, and while my opinion of Henry James as a writer is not relevant to my use of his story, I just want to go on record saying that there is no writer who frustrates me more than Henry James in his later period. I find Joyce’s Ulysses – dammit, Joyce’s Finnegan’s Wake – easier to read and to make sense of than the prose of Henry James in his later period. When I read one of James’s sentences I often feel that it was created by an algorithm that has been fed a list of English words classified by part of speech and an extensive set of grammatical rules — but has been given no information about what the words mean. Here is a representative — note: representative, not unusual, not exaggerated — sentence from The Sense of the Past: “Just these high considerations were in all probability the influence most active in his attitude toward the only approach to an adverse interest with which he was to perceive himself confronted.“ Just for fun, here’s another one: “He had even for this one of those rarest reaches of apprehension on which he had been living and soaring for the past hour and which represented the joy he had just reasseverated; impatience was surely one of her bright marks, but he saw that to live with her would be to find her often deny it in ways unforeseen and that seemed for the moment to show themselves as the most delightful things in nature.” I read sentences like these and think I’m developing some rare and deadly form of aphasia.

On Monday Robert Macfarlane will be hosting a Twitter book club on W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, which is one of the most compelling and memorable books I have ever encountered. I’ve read it three times now and hope to read it at least twice more.

Years ago, in the first flush of my fascination with it, I bought a copy and sent it to Frederick Buechner, who, if you don’t know, is one the best writers of English now living. He read it, and wrote back to say, “I have no idea what any of that means but it is absolutely mesmerizing.” Which is a pretty good summary.

I am re-reading the Palliser novels, for the first time in 20 years, which means I have largely forgotten what happens in them, and I am reminded that Trollope really is the most underrated novelist in the world. The casualness of his manner, and his intermittent insistence is that he is telling simple and insignificant stories, disguise from us just how penetrating his mind was, how clearly he sees the inmost workings of his characters’ lives, and how justly he deals out condemnation and mercy alike. I’m reading Can You Forgive Her? right now, and there is an extraordinary moment when George Vavasor has entered Parliament, having run a successful race thanks to the money he has extracted from his cousin Alice, whom he has manipulated into agreeing to marry him though he knows perfectly well that she does not love him. So when he comes to see her immediately after his election, he begins by thanking her for her financial contribution to his success – thanks which she does not want – but then strives to extract from her some expression of affection which she knows she does not feel. And Trollope pauses in the middle of George’s conversation with Alice and says, with brutal simplicity, “He should have been more of a rascal or less.” It’s one of the most devastating comments that any novelist has made about one of his characters.

George wants to be treated as an honorable man without being one. He wants Alice to give him credit for virtues and intentions which he has in a thousand ways made it clear that he does not possess. He insists upon being given credit for traits which as soon as he walks away from her he repudiates mockingly. He should have been more of a rascal or less. He should have frankly acknowledged the terms on which he and Alice have come to an agreement, or realized that he desperately needed to amend his life. But he does neither, and by doing neither makes himself and Alice equally miserable.

Can You Forgive Her? contains plenty of the broadish comedy that Trollope did so well – the protracted attempts of the farmer Mr Cheeseacre to woo the widow Greenow really are funny, even if there is more of it than one might think ideal – but the effect of these scenes is primarily to relieve the tension of what in other respects is a rather agonizing novel to read. Some may think “Ah, well, we know that everything will turn out all right in the end” – but we do not know that, not in a Trollope novel. Some of his most appealing and memorable characters (Lady Laura Kennedy, Lily Dale) do not receive the eucatastrophic resolution we would rightly expect from a lesser writer. If you know that, you know that you cannot simply expect a happy ending for his protagonists.

Which makes it all the more delightful when they get one.

The public sphere is crucial to the intellectual, though its fragile structure is undergoing an accelerated process of decay. The nostalgic question, ‘Where have all the intellectuals gone?’ misses the point. You can’t have committed intellectuals if you don’t have the readers to address the ideas to.

Those who once might have been readers are all shouting at one another on Twitter. One could argue that social media are not an extension of the public sphere but the antithesis of it. Habermas doesn’t want to rule out the possibility of things getting better: “Perhaps with time we will learn to manage the social networks in a civilized manner.” But he doesn’t seem especially hopeful: “I am too old to judge the cultural impulse that the new media is giving birth to. But it annoys me that it’s the first media revolution in the history of mankind to first and foremost serve economic as opposed to cultural ends.”

The really interesting point here is that you can’t have genuine public intellectuals if you don’t have a sizable class of people who are able to read — who can understand arguments and assess them shrewdly and fairly. But anyone has been on social media knows how rare such ability is, how regularly (almost unerringly) people respond to what others have written without having, in any meaningful sense, read it.

So maybe one of the most important questions we who are concerned about our common culture can ask ourselves is this: How do we bring reading back?

I’m pretty sure my body has a peculiar electromagnetic field that wreaks havoc on the batteries of electronic devices. Not all of them: all of my iPhones have had more-or-less the advertised battery life. But all of my Mac laptops, going back fifteen years, have gotten around four hours from a charge. No announced improvement in battery power has ever changed that. (I’m typing this on a MacBook that’s supposed to get around 10 hours from a charge under normal use. It gets four. It has always gotten four.) And my Kindles have been even worse — though never quite as bad as my new Kindle Oasis, which promises “weeks” of battery life on a single charge and gets … about two days. And that’s with limited use of the light. Two days.

So I’m sending it back. It’s all boxed up and ready to go, which leaves me, if I want to read on an e-reader, with this old thing:

And you know, it’s not bad — not bad at all. Yes, it’s a little heavier and the type isn’t quite as sharp, but it has advantages: no touchscreen, so I don’t have to wipe off prints; a hardware keyboard, which is much more user-friendly for someone like me who actually annotates books; underlining of marked text, which I think more readable and less distracting than highlighting. It doesn’t have a light, of course, but I rarely use the light because I read outdoors a lot and even when reading inside it’s easier on my eyes to read by lamplight.

So maybe I’ll just keep using this device I bought seven years ago — as long as the battery holds out.

I’ve spent many unedifying hours reading books by biblical scholars in ways that have not been … ideal for my purposes. Today I’m going to share with you all some important lessons I’ve learned through my suffering.

1) The first part of the book will explain in mind-numbing detail how the author situates himself or herself in relation to several hundred other biblical critics. (Maybe only several dozen, but it will feel like several hundred.) The author will insist on explaining to you at, frankly, shocking length that there are

(a) scholars whose position he or she doesn’t agree with at all but whose work, in the cause of fairness, must be described thoroughly;

(b) scholars whose position he or she has partial sympathy with and whose work therefore must be described even more thoroughly; and

(c) scholars whose position he or she largely agrees with, though hopes to extend, and whose work must therefore be described until you are old and gray and full of sleep.

Skip all this. Seriously, don’t read any of it. If you’re not a member of the guild it will be neither interesting nor valuable. (All scholars interact with previous scholars in their chosen subject, but biblical scholars are in my experience unique in their devotion to “literature reviews” and “methodological introductions.” One gets the sense that they would write nothing but literature reviews and methodological introductions if they could get away with it.)

2) Next, read the last chapter, or conclusion. This is the place where you’ll find out what the author actually believes and get at least an outline of why he or she believes it. You should scrutinize the conclusion with great attentiveness, because almost all the good stuff is there.

3) As I say, the conclusion will give you at least an outline of why the author holds his or her views, but sometimes you won’t get as much detail as you need. No worries! The author will sometimes say things like “As I argued in Chapter 3” or “As noted above (pp. 173–79)” — so follow those bread crumbs and see the complete argument about whatever you’re interested in. And don’t bother with what you’re not interested in.

And that’s it! Three easy steps to getting great benefit from biblical scholarship at the least cost to your health and sanity.

There is only one way to read, which is to browse in libraries and bookshops, picking up books that attract you, reading only those, dropping them when they bore you, skipping the parts that drag — and never, never reading anything because you feel you ought, or because it is part of a trend or a movement. Remember that the book which bores you when you are twenty or thirty will open doors for you when you are forty or fifty — and vice-versa. Don’t read a book out of its right time for you.

Doris Lessing, 1971 introduction to The Golden Notebook (via austinkleon)

I had never seen this passage before, but it certainly chimes with a section of my book The Pleasures of Reading in an Age of Distraction:

I was twenty years old before I failed to finish a book I had started: it was The Recognitions, a novel by William Gaddis, and I gave up, after an extended period of moral paralysis, at page 666. That day I grieved, feeling that I had been forced from some noble pedestal; but I woke up the next morning with my soul singing. After all, though I would never get back the hours I had devoted to those 666 pages, the hours I would have spent ploughing through the remaining 400 were mine to spend as I would. I had been granted time as a pure and sweet gift.