It’s been widely reported that the U.K. children’s book publisher Puffin is producing a new edition of Roald Dahl’s books with all the wrongthink – or as much of it as possible; this is Roald Dahl, after all – taken out.

Sometimes they’re editing Dahl-as-such and sometimes his characters. The gluttonous Augustus Gloop in Charlie and the Chocolate Factory is no longer described as “fat” but rather as “enormous,” thus leaving readers free to imagine that he’s a powerlifter in a high weight classification. Dahl himself is the insensitive one there. When a character says of another character “I’d knock her flat,” Puffin’s supersensitives replace that fierce language with “I’d give her a right talking to.” (But what if the character speaking is the type to use strong language? Or do bad things? Shall we have a version of Crime and Punishment in which Raskolnikov skulks around St. Petersburg fantasizing about giving his landlady a right talking to?)

Sometimes it’s hard to tell what offense the supersensitives imagine: It’s not clear that calling someone a “trickster” rather than a “saucy beast” makes an improvement in manners; what is clear is that the meaning is completely different. But: while Dahl referred to Mrs. Twit as “ugly and beastly,” she is now just called “beastly,” though I cannot imagine why calling someone a “beast” is unacceptable but calling them “beastly” is hunky-dory.

One could go on about this silliness all day, and many are doing so, but I actually think there’s an important point to be made in response to these changes: the people doing it have no right to do so. They have the legal right, but what they’re doing is morally wrong.

It’s morally wrong first of all because it’s dishonest. The books will still be sold as Roald Dahl’s – it is his name that will draw readers to these volumes – but they are in fact Dahl’s involuntary collaboration with people who find some of his words and phrases intolerable. That this is so should be announced on the book’s covers – but you may be sure that it will not be. If you own the rights to Dahl’s books but passionately believe that what Dahl wrote is too offensive for today’s readers to face, then your only honorable option is to stop selling the freakin’ books.

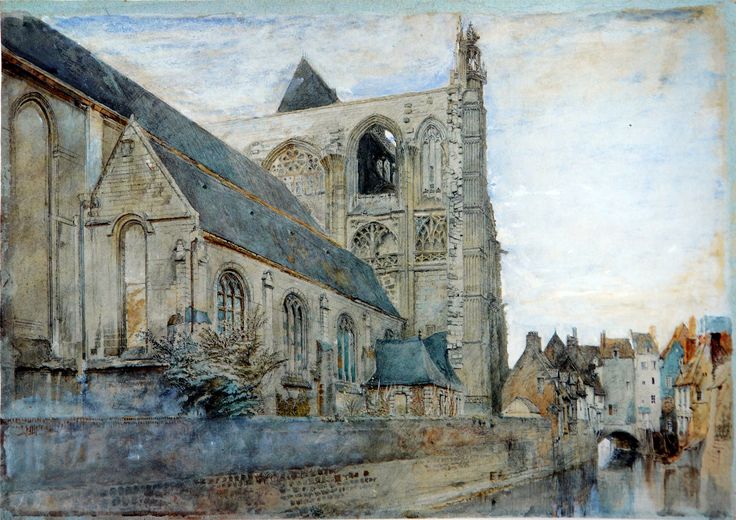

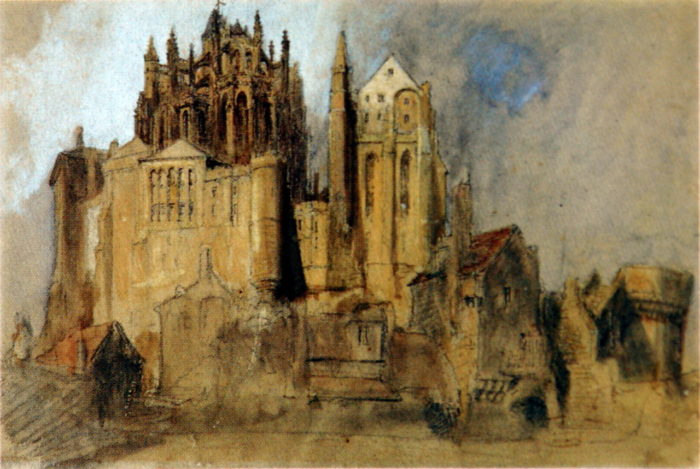

This may sound like an odd digression, but bear with me: I’ve been re-reading The Seven Lamps of Architecture, in which Ruskin confronts the widespread practice, in the England of his time, of either dramatically renovating or tearing down old buildings.

First, Ruskin says, when a building is stripped down to its shell and given an entirely new interior, those who do it should call it what it is: destruction. “But, it is said, there may come a necessity for restoration! Granted. Look the necessity full in the face, and understand it on its own terms. It is a necessity for destruction. Accept it as such, pull the building down, throw its stones into neglected corners, make ballast of them, or mortar, if you will; but do it honestly, and do not set up a Lie in their place.” So also I say: Do not set up a Lie in place of Roald Dahl’s actual books. If they are intolerable, do not tolerate them. Let them go out of print, take the digital editions off the market, and force those of us who are bad enough to desire the books to scour second-hand bookstores for them.

But let’s pursue Ruskin’s argument a bit further. Sometimes a building is torn down altogether, razed to the very ground. What does Ruskin say about that?

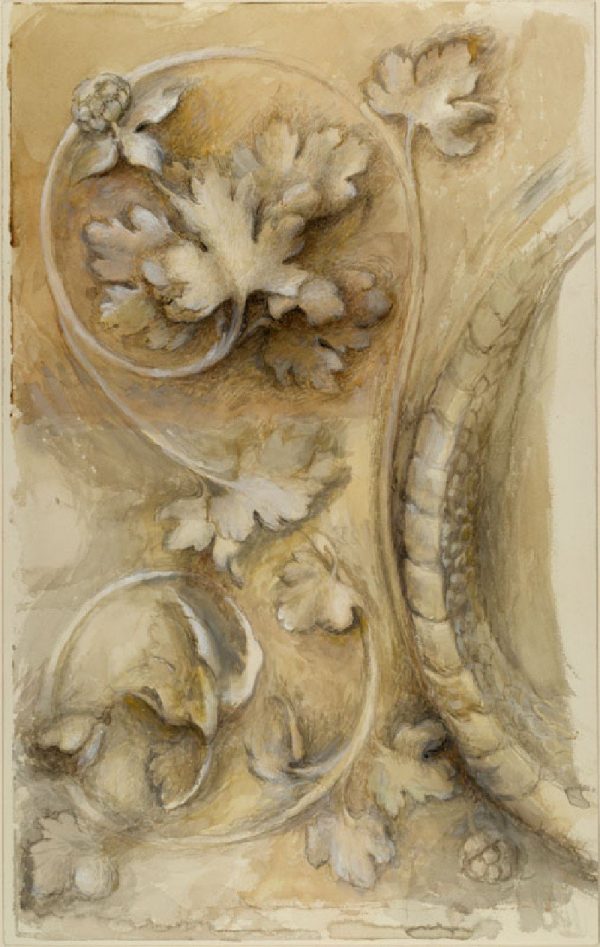

Of more wanton or ignorant ravage it is vain to speak; my words will not reach those who commit them, and yet, be it heard or not, I must not leave the truth unstated, that it is again no question of expediency or feeling whether we shall preserve the buildings of past times or not. We have no right whatever to touch them. They are not ours. They belong partly to those who built them, and partly to all the generations of mankind who are to follow us. The dead have still their right in them: that which they laboured for, the praise of achievement or the expression of religious feeling, or whatsoever else it might be which in those buildings they intended to be permanent, we have no right to obliterate. What we have ourselves built, we are at liberty to throw down; but what other men gave their strength and wealth and life to accomplish, their right over does not pass away with their death; still less is the right to the use of what they have left vested in us only. It belongs to all their successors. It may hereafter be a subject of sorrow, or a cause of injury, to millions, that we have consulted our present convenience by casting down such buildings as we choose to dispense with. That sorrow, that loss, we have no right to inflict.

As astonishingly eloquent and impassioned declaration, which, in regard to architecture, one might plausibly disagree with. (Though not easily, I think. I may return to this in another post.) Buildings take up a good deal of space, and the maintenance of them can be expensive; there certainly are circumstances in which demolition is indeed necessary. Ruskin, remember, grants this point, though not without certain hedgings.

But Ruskin’s argument is irrefutable when it comes to the other arts of the past – poetry, story, music, painting, sculpture. There can be no justification for mutilating or destroying them to suit “our present convenience.” We do not know whether later generations will think as we do, will share our preferences and our sensitivities; to preserve the art of the past is to show respect not only for that past but also for our possible futures. And it is to establish a standard for how we wish to be treated by our descendants.

Even the Victorians (and some of their successors) who thought sculptures of naked men too offensive for ladies to see merely covered the pudenda with plaster leaves — the penises themselves remained untouched, for later generations, and less delicate viewers, to see if they wish. (Some years ago I published an essay on this practice — and related matters.)

Perhaps Puffin — since there’s no way in hell they’re gonna give up the chance to make bank — can provide two versions, sort of like like New Coke and Coke Classic, clearly differentiated by label. They could advertise the one and not advertise the other; they could make their preferences clear; they could say “If you are a Good Person you will purchase our sanitized versions rather than the nastiness written by Roald Dahl himself.” And then people could buy the version they want.

Wanna place bets on which version readers would choose? But I don’t think we’ll find out. The one canonical rule of the supersensitives is: The reader is always wrong. Because any genuine reader is, by definition, not a supersensitive.