James Agee, the best writer ever to review movies for a living, was never better than in his review for The Nation of William Wyler’s The Best Years of Our Lives (1946) — for which, FYI, there will be many spoilers below. The movie concerns three returning servicemen — each struggling in his own way to find his way back into the civilian world — and the people who love them. “At its worst,” Agee writes, “this story is very annoying in its patness, its timidity, its slithering attempts to pretend to face and by that pretense to dodge in the most shameful way possible its own fullest meanings and possibilities.” He goes on in this vein for some time, and sums up his critique thus:

In fact, it would be possible, I don’t doubt, to call the whole picture just one long pious piece of deceit and self-deceit, embarrassed by hot flashes of talent, conscience, truthfulness, and dignity. And it is anyhow more than possible, it is unhappily obligatory, to observe that a good deal which might have been very fine, even great, and which is handled mainly by people who could have done, and done perfectly, all the best that could have been developed out of the idea, is here either murdered in its cradle or reduced to manageable good citizenship in the early stages of grade school.

Thus ended his review — or, rather, the first half of his review, for in the next week’s issue he returned to explain why he absolutely loved the movie. And that, friends, is Exhibit A in my case for James Agee as Top Movie Reviewer.

In that second half of his review he singles out the photography of Gregg Toland — indeed, though Agee did not know it, The Best Years would be one of Toland’s last films: he died in 1948 at the age of forty-four, and thus the film world lost its greatest cinematographer. “I can’t remember a more thoroughly satisfying job of photography, in an American movie, since Greed. Aesthetically and in its emotional feeling for people and their surroundings, Toland’s work in this film makes me think of the photographs of Walker Evans.” (Agee had, famously, collaborated with Evans on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.)

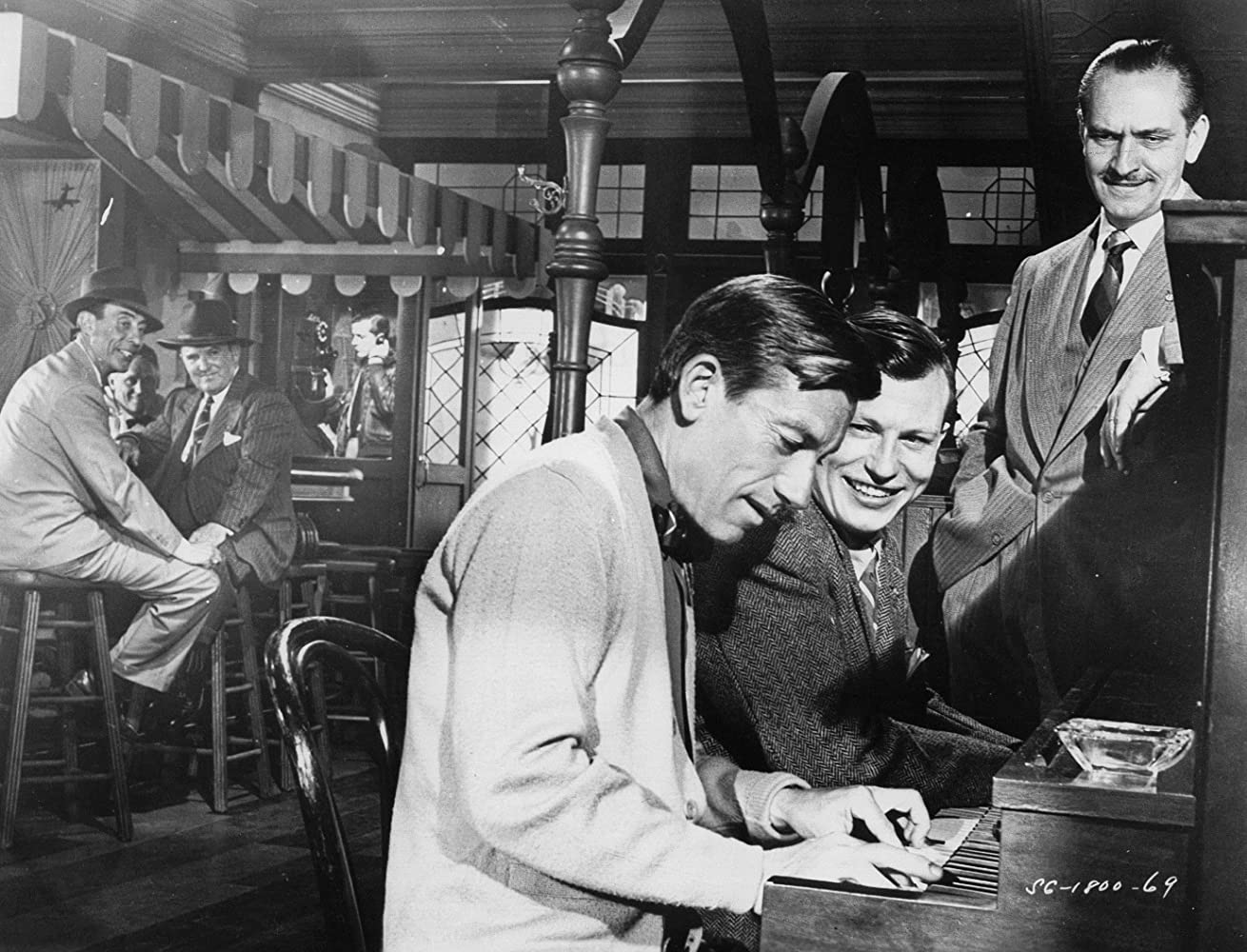

Let’s take one scene, a celebrated one, as an example of Toland’s skill — and of Wyler’s imaginative direction. Al Stephenson has a problem: his daughter Peggy is in love with another returning serviceman, Fred Derry; but Fred is married. Al asks Fred to meet him at a restaurant/bar called Butch’s, and he tells Fred not to see Peggy again. Fred is grieved, but he agrees; he’ll call her to cut all ties. As he enters the telephone booth next to the bar, Homer — the third serviceman in this story, a sailor who has lost his hands in a fire on his ship, comes in. (See the story of the actor, Harold Russell.) Butch, the owner, is his uncle, and Homer wants Al to watch him and Butch play a song on the piano — they’ve been practicing, Homer tapping the keys with his hooks and Butch filling in. Al’s mind is elsewhere, but he agrees.

The above shot appears to be a still from an alternate take, because in the movie Homer plays the melody while Butch provides bassline harmony. And in that scene Al can’t keep his eyes on the piano: he keeps looking back at Fred on the phone. But you can see here the famous Toland depth of field and a real compositional genius: Fred is a tiny figure in the back left, and yet he’s as present and vivid to the viewer as the jolly musicians in the foreground. It’s storytelling by photography, and it’s brilliant. Here’s a good clip.

There’s a scene later in the movie when Homer — who has been avoiding his fiancée Wilma because, he believes, she doesn’t understand how hard it would be to live with his disability — invites her to his room in his family’s house to see how helpless he is when he removes his prosthetic harness. (This is the one time we see Homer consciously acknowledging his limitations.) And when, instead of fleeing in horror, Wilma with infinite tenderness buttons up his pajama top, well, I let fall a manly tear.

Anyway, that clears the way for Homer and Wilma: the movie concludes with their wedding. And here the genius of Toland and Wyler comes to our aid again:

Foreground right: Homer and Wilma. Background center: Al and his wife Milly, and then, on the left, their daughter Peggy — who only has eyes for the now-divorced Fred, Homer’s best man, foreground left. (Al and Milly, like everyone else, look at the marrying couple.) And, as the scene unfolds, we discover that Fred only has eyes for her. It’s brilliant: the words of the service of Holy Matrimony unfold, and as happy as we are for Homer and Wilma, our attentions and our emotions are divided.

Teresa Wright plays Peggy, and Agee, in the second half of his review, singled her out for particular praise:

Almost without exception, down through such virtually noiseless bit roles as that of the mother of the sailor’s fiancé, this film is so well cast and acted that there was no possible room to speak of all the people I wish I might. I cannot, however, resist speaking, briefly anyhow, of Teresa Wright.… She has always been one of the very few women in movies who really had a face.… She has also always used this translucent face with a delicate and exciting talent as an actress, and with something of a novelist’s perceptiveness behind the talent. And … she has never been around nearly enough. This new performance of hers, entirely lacking in big scenes, tricks, or obstreperousness – one can hardly think of it as acting – seems to me one of the wisest and most beautiful pieces of work I have seen in years. If the picture had none of the hundreds of other things that it has to recommend it, I could watch it a dozen times over for that personality and its mastery alone.

The story of how Teresa Wright ran afoul of the studio system, and more particularly of Sam Goldwyn, and lost what could have been an extraordinary career, has been told in several different ways, most of which blame Goldwyn and the system. David Thomson, whose judgment is typically acute, seems to think that her decline was inevitable because she was “not glamorous enough to be a star,” was “relatively plain-faced.” Wright may not have been a classic beauty, but plain is not the word to describe that emotionally “translucent” face, and not much in all of movies is lovelier than her expression in the final frames of The Best Years of Our Lives, when Fred declares his love:

•

Abbas Kiorastami (1940–2016) was an Iranian film director (also a screenwriter, painter, photographer, poet) who made curious films — often seemingly simple, featuring quasi-documentary techniques, but hiding a shrewd complexity. His last film, which he had not quite completed at his death, was 24 Frames, which begins by gently, subtly animating Bruegel’s The Hunters in the Snow and then goes on to animate — always subtly, usually gently, sometimes disturbingly — a series of photographs taken by Kiorastami himself. It’s a kind of extended meditation on the very idea of a frame — a demarcated space within the confines of which we see, and see differently. See, perhaps, more vividly.

But Frame 24 is rather different. Like several of the others, it features a window. Through that window you see a night sky, and trees waving in the wind of a winter storm; in addition to the wind and rain pinging the glass, you hear, of all things, Andrew Lloyd Webber’s “Love Never Dies.” (Most the movie’s sounds are natural, though music is occasional.) In the foreground is a desk, at which a young woman is slumped over in sleep. Just above her drowsing head there’s a computer screen, and on that screen we see, in a very slow frame-by-frame advance, the last shot of The Best Years of Our Lives.

Gradually the light increases — dawn is coming — and (inch by inch) Peggy raises her gloved hand to embrace Fred, and Fred leans forward to kiss her, and down (inch by inch) goes her hat, and then: THE END.

Thus Abbas Kiorastami makes his last bow. And I find it really quite touching that his final message to us, or a big part of it anyway, is simply this: What could be more wonderful than the movies?