Should you happen to want to think about Augustine’s City of God (hereafter CD for Civitate Dei) in sociological terms – which is certainly not the only and perhaps not the best way of thinking about it – but should you want to consider it sociologically, then I would suggest that you first read China Miéville’s novel The City and the City.

Like Augustine’s masterwork, Miéville’s novel is concerned with two cities that have a complex, fraught, and not-always-comprehensible relation to one another. And like the City of God and City of Man, Besźel and Ul Qoma occupy the same physical space. Well, sort of. I’ll try to explain.

The protagonist of the novel is a police inspector named Tyador Borlú, who lives and works in a city called Besźel, which appears to be somewhere in the Balkans. (More on that in a later post.) We first get a sense that there’s something a little odd about this situation early in the book, when Borlú sees an old woman on the street:

With a hard start, I realised that she was not on GunterStrász at all, and that I should not have seen her. Immediately and flustered I looked away, and she did the same, with the same speed. I raised my head, towards an aircraft on its final descent. When after some seconds I looked back up, unnoticing the old woman stepping heavily away, I looked carefully instead of at her in her foreign street at the facades of the nearby and local GunterStrász, that depressed zone.

Her “foreign street,” we eventually learn, is in the city of Ul Qoma, which is the topological double, the “topolganger,” of Besźel. What does that mean? Much is never explained directly in the book, so any answer will necessarily involve interpretation, but …: If you were a resident of neither Besźel nor Ul Qoma and were dropped into their physical space, you would see one city. But the people who live there are trained almost from birth to notice the differences – in language, in food, in dress, even in basic bodily movement (“physical vernacular”) – and to somehow suppress their sensory awareness of the other city. Should that suppression fail, as it fails Borlú when he sees the old Ul Qoman woman, one must “unsee” – or “unhear” if you notice a foreign voice or the siren of a foreign ambulance, or even “unsmell” should the aromas of an alien bakery find their way to your nose. The separate identities of the two cities are sustained by an obsessively inculcated mutual incomprehension – or, more precisely, imperception.

As a citizen of Besźel or Ul Qoma navigates this topology, he or she is always aware that most areas are total – they are only in Besźel or only in Ul Qoma, and in such places the topolganger is alter – while others are crosshatched, that is, belonging somehow to both cities. (Navigating these can be difficult: one must take pains to avoid touching citizens of the other city, and must constantly unsee, unhear, unsmell. It’s stressful.) A few places are dissensi, disputed – each city claims them. Such disputes, and many others that inevitably arise, are adjudicated in the great administrative center called Copula Hall – the only building with the same name, and the same function, in both cities, and the only place where one can legally pass from one city to another:

If someone needed to go to a house physically next door to their own but in the neighbouring city, it was in a different road in an unfriendly power. That is what foreigners rarely understand. A Besź dweller cannot walk a few paces next door into an alter house without breach. But pass through Copula Hall and she or he might leave Besźel, and at the end of the hall come back to exactly (corporeally) where they had just been, but in another country, a tourist, a marvelling visitor, to a street that shared the latitude-longitude of their own address, a street they had never visited before, whose architecture they had always unseen, to the Ul Qoman house sitting next to and a whole city away from their own building, unvisible there now they had come through, all the way across the Breach, back home.

(Miéville gets his pronouns confused there. It happens even to professionals.) Some people believe – and this is important to the book but will not be stressed in this post – that there is a third city in the same place, one comprised of territories that Besźel thinks belong to Ul Qoma and Ul Qoma thinks belong to Besźel. This possibly imaginary city is called Orcinny, Miéville’s tip of the hat to Ursula K. Le Guin’s imaginary Central European country Orsinia.

To violate the categorical imperative, this Prime Directive of imperception, is to “breach,” and when you breach you become subject to the fierce power known as … Breach. When the boundaries are in any way violated, the “avatars” of Breach suddenly and mysteriously appear to deal with the violation, and in some cases the breacher is never seen again. Residents of both cities live in absolute terror of Breach, which they believe to be omniscient. After all, if Breach were not omniscient, how could you get in trouble just for seeing someone, or smelling a pastry baking? No ordinary mortal could know what’s going on in your head.

It’s only late in the book that we begin to question whether Breach really is that powerful. What if the people of the two cities are not policed in the way they fear, but instead are merely self-policing? We are told in the book that there was at some point in the distant past a Cleavage that separated the two cities, which suggests that until then the place was a single city; but no one seems to understand precisely when the Cleavage happened or why. Archeologists visit the two cities (primarily Ul Qoma) to study the artifacts of the Precursor culture, the culture that existed before the Cleavage, but those artifacts are confusing, featuring in the same strata what seem to be remains of widely varying civilizations. Rumors suggest that these artifacts manifest “questionable physics,” but we’re not told what that means, perhaps because no one knows. If for much of the book we are encouraged to think of the Cleavage and its resulting urban parallelism as a paranormal event, in the novel’s latter stages we begin to wonder whether there’s anything going on here other than group psychosis, the “madness of crowds” – maybe only plain old propaganda. None of these questions is answered.

•

At the outset of his massive work – simultaneously historical, sociological, ethnographic, and theological – Augustine writes,

I have taken upon myself the task of defending the glorious City of God against those who prefer their own gods to the Founder of that City. I treat of it both as it exists in this world of time, a stranger among the ungodly, living by faith, and as it stands in the security of its everlasting seat. This security it now awaits in steadfast patience, until ‘justice returns to judgement’; but it is to attain it hereafter in virtue of its ascendancy over its enemies, when the final victory is won and peace established. (CD I.1)

Already, here at the outset, we have a situation potentially more complicated than that of Miéville’s novel. For while we see the beginnings here of a contrast to the City of Man – the city built and sustained by the “ungodly,” those who reject the God who has founded His own city – we also see the eternal City ontologically doubled: at once (a) on a seemingly uncertain pilgrimage and (b) already and eternally victorious. And there is another complication: the City of God is not quite coterminous with the Church. For one thing, the former contains angels and the latter doesn’t. (CD XI.9: “The holy angels … form the greater part of that City, and the more blessed part, in that they have never been on pilgrimage in a strange land.”) Moreover, Augustine occasionally acknowledges that there may be some who do not belong to the Church who nevertheless belong to the City of God. So whatever else we say about the City of God, it’s bigger than the Church. And anyway, as David Knowles points out in his magisterial introduction to the edition I’m reading, Augustine in this work is not interested in the Church.

But Christians today are certainly more likely to think of the Church than of the City of God. At most what we tend to see is the Church as a kind of outpost, as it were, of the City of God; often it seems to be surrounded by its enemies. This is not wholly wrong but not wholly correct either. Near the beginning of The Screwtape Letters the demon Screwtape says to the junior demon Wormwood,

One of our great allies at present is the Church itself. Do not misunderstand me. I do not mean the Church as we see her spread out through all time and space and rooted in eternity, terrible as an army with banners. That, I confess, is a spectacle which makes our boldest tempters uneasy. But fortunately it is quite invisible to these humans. All your patient sees is the half-finished, sham Gothic erection on the new building estate.

“Invisible”? — or perhaps, as Miéville suggests, unvisible, deliberately or half-deliberately unseen? One way to think about that sham-Gothic building is as belonging fully to the City of God – it is, as it were, total, and in relation to it the City of Man is alter. To see it that way would be to perceive “a serious house on serious earth” indeed. In the doubled city of Miéville’s novel, strangers who breach, who wander from one city to another heedlessly, are treated with compassion; they don’t know, they can’t be expected to know. Still more is this true when a citizen of the City of Man – Philip Larkin, say, whom I have just quoted – wanders into a church, because if Besźel and Ul Qoma are constituted by separation, and most of their citizens seem to wish only to make that separation more perfect, both of Augustine’s cities proselytize: though some of the individual proselytizers are more charitable and generous than others, each wants, ultimately, the end of the other.

In Miéville’s imagined world, separation is questioned only by unificationists (unifs, for short), who want to undo the Cleavage and make the city again one; here, almost everyone seems to know that that’s not possible. Ultimately, we all seem to believe, one of the cities will be triumphant and the other will end. (CD XV.4: “The earthly city will not be everlasting; for when it is condemned to the final punishment it will no longer be a city.” Voltaire: “Écrasez l’infâme!”) Unification achieved only through elimination or absorption. As a result, every inch of earthly territory is dissensi: such disputes are usually mute and implicit, but they become explicit whenever a state legislature mandates the posting of the Ten Commandments in public-school classrooms, or when courts demand that Christian bakers or florists or web designers make obeisance to the newest imperatives of the City of Man.

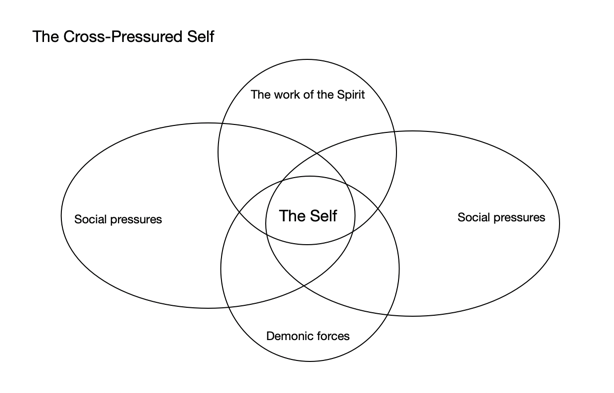

And even when there are no open disputes, the citizens of both cities must regularly confront rival beliefs, rival values, rival ideals. In a few places one particular city may be nearly total, but the internet and the TV bring news from the other city. Such news most unsee, with a shrug or with a muttered imprecation, but tension always threatens; and almost all of us are aware that crosshatching is not rare but nearly ubiquitous. We may then treasure those moments, those places, where the other city can be felt to be wholly alter.

At the end of The City and the City, the future of Besźel and Ul Qoma remains in question. But here, in this world, few doubt the ultimate outcome. Each city believes it will be, in the end, victorious. But what to do in the meantime? This is one of Augustine’s key questions, though it takes him several hundred pages to get to it, and even then his approach is often indirect. More about all that in another post.