My wife Teri and I first met Fred Buechner in 1984, when he came to Wheaton College for a ceremony acknowledging the donation of his papers to the college’s Special Collections. We only spoke briefly at that time, and my chief memory of our conversation is Fred’s passionate impromptu defense of Anthony Trollope as a great and deep novelist – not the relatively lightweight storyteller, the maker of fictional comfort food, that he is often said to be. I had not read Trollope at that time, and when I first sat down with his books I was glad to recall Fred’s words – they made me a better reader of that much-loved but still-underrated writer.

The next year Fred returned to Wheaton for an eight-week stint as a visiting professor, an adventure that he describes in the third of his series of brief memoirs, Telling Secrets. A couple of years earlier he had spent a term teaching homiletics at Harvard Divinity School, an experience he found always perplexing and sometimes discouraging:

Whatever may have bound my students together elsewhere in the way of common belief or commitment, I was much more aware of what divided them. It did not take me long to discover early in the game, as you might have thought I would have known before I came, that a number of them were Unitarian Universalists who by their own definition were humanist atheists. One of them, a woman about my age, came to see me in my office one day to say that although many of the things I had to teach about preaching she found interesting enough, few of them were of any practical use to people like her who did not believe in God. I asked her what it was she did believe in, and I remember the air of something like wistfulness with which she said that whatever it was, it was hard to put into words. I could sympathize with that, having much difficulty putting such things into words over the years myself, but at the same time I felt somehow floored and depressed by what she said. I think things like peace, kindness, social responsibility, honesty were the things she believed in – and maybe she was right, maybe that is the best there is to believe in and all there is – but it was hard for me to imagine giving sermons about such things. I could imagine lecturing about them or writing editorials about them, but I could not imagine standing up in a pulpit in a black gown with a stained glass window overhead and a Bible open on the lectern and the final chords of the sermon hymn fading away into the shadows and preaching about them. I realized that if ideas were all I had to preach, I would take up some other line of work.

This experience was still fresh in Fred’s mind when he came to Wheaton – and if you want to know what he thought about that event, well, you should read Telling Secrets, which is by any measure a beautiful book and more than worth reading even if you don’t care a fig about Harvard or Wheaton.

Teri and I spent a good bit of time with Fred during that eight-week period: we went to the Wheaton Theater to see Return to Oz (the Oz books were always totemic and iconic for Fred); on weekends we traveled into Chicago to eat at fancy restaurants, meals for which Fred always paid, referring to himself as “the rich man from the east”; and two or three times we ate at a local restaurant that he somewhat comically grew attached to. It was called the Viking, and was a more or less standard Midwestern steakhouse with one peculiarity on the menu: they served a spinach salad that they would flame at your table. At one point a salad was set afire directly behind Teri and me, and we flinched forward in our seats as the flames warmed our necks, which caused Fred to lean over and whisper conspiratorially to Teri: “This is a dangerous restaurant.” (Fred loved Teri, in part because she was the same age as one of his daughters – he and his wife Judy had three daughters – and he would occasionally say to me, “I only put up with you because of your wife.”)

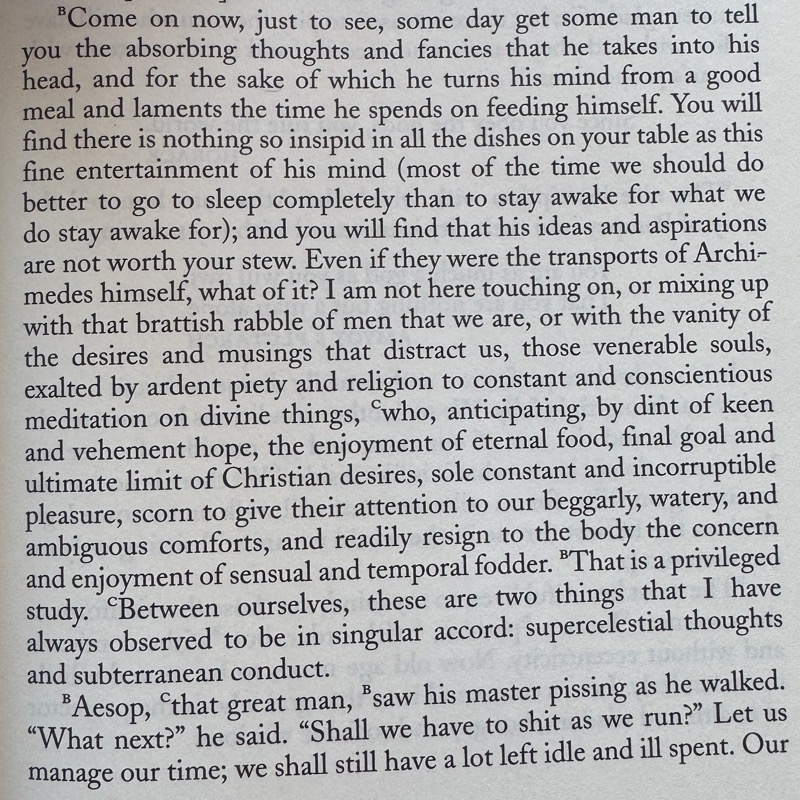

A year or so later, I think, the Viking was badly damaged in a fire, and since nothing could have been less surprising, I hastily wrote Fred a letter about it. The relevant portion of his reply:

And the fiery fate of the Viking! I can only hope that by now it is back in commission again. I remember with extraordinary pleasure – together with so many other things about my Wheaton weeks – my suppers there. Steak, medium rare, with a baked potato and salad, and a glass or two of red wine for the stomach’s sake. I would always bring a book to read as I ate, but most of the time I would just sit there feasting my eyes on my fellow diners and the flames from the various chafing dishes ablaze around me. Had I only thought to warn them.

On several occasions that semester I got to hear Fred read from his own work, and he was an absolutely marvelous reader. His writing was, I think, and this is true of most of the best writers, emergent from speech. He loathed excessive punctuation, and a sentence didn’t have to have a lot of punctuation for him to consider it excessive: he wanted the pauses and emphases to be clear from the words. Read that passage from Telling Secrets aloud; it’s a marvel of timing and rhythm, like the phrasing of a great jazz singer. Or consider this passage from what I think is his best novel, Son of Laughter – a retelling of the story of Jacob, who refers to YHWH as the Fear:

The unclean blood no longer clung to our hands, but the small gods clung still to our hearts. They clung with silver fingers, with fingerless hands of wood and baked clay. Like rats, the gods gibbered in our hearts about the rich gifts they have for giving to us. The gods give rain. The swelling udder they give and the sweet fig, the plump ear of grain, the ooze of oil. They give sons. To Laban they gave cunning. They give their names as the Fear, at the Jabbok, refused me his when I asked it, and a god named is a god summoned. The Fear comes when he comes. It is the Fear who summons. The gods give in return for your gifts to them: the strangled dove, the burnt ox, the first fruit. There are those who give them their firstborn even, the child bound to the altar for knifing as Abraham bound Isaac till the Fear of his mercy bade the urine-soaked old man unbind him. The Fear gives to the empty-handed, the empty-hearted, as to me from the stone stair he gave promise and blessing, and gave them also to Isaac before me, to Abraham before Isaac, all of us wanderers only, herdsmen and planters moving with the seasons as gales of dry sand move with the wind. In return it is only the heart’s trust that the Fear asks. Trust him though you cannot see him and he has no silver hand to hold. Trust him though you have no name to call him by, though out of the black night he leaps like a stranger to cripple and bless.

Fred was one of the great prose stylists of his era, and while I don’t write like him — I don’t have the skill, and in any case the sorts of things that I write about and the ways that I write about them demand a different style than he developed — I’ve learned a great deal about the writing of prose from him. He made me think about prose in a different way than I ever had before, and if I have ever managed to write well, I think I owe a lot of that success to Fred.

But the most important lessons that I learned from Fred, lessons I’m still learning from him, arise from his temperament as a Christian. Not his beliefs, specifically, but his manner of approaching God and approaching the world. It was open-minded, to be sure, but more than that it was open-hearted, and continually aware of the ways that the world, like the Fear who made the world, can both hurt us and bless us. (He and I shared a great love for the passage in Anna Karenina in which Kitty gives birth to her first child and Levin, the new father, immediately thinks: Now the world has so many more ways to hurt me.) Fred was always fascinated by the many ways the God who loves us can use both the wounds and the blessings to form and shape our very being. Fred manifested – and in some ways this is even more evident from his personality than from his writing – a kind of gently ironic but faithful and hopeful bemusement. It’s very hard to describe, but I found it enormously winning, and the absence of it from the world is I think a real loss.

We hadn’t often been in touch in the past fifteen years. Once, I sent him a copy of W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, a book I deeply love and that I felt sure Fred would also love. He wrote back to tell me that he had read it and indeed loved it, though he went on to say that he had absolutely no idea what it was about. Correspondence languished after that, alas. I thought many times over the last few years of writing to him, but I didn’t know what kind of shape he was in, and I didn’t know whether our relationship had ever been close enough to deserve that. I now regret not having made connection, as one does.

The last time Teri and I saw Fred and his quietly gracious wife Judy was at Calvin College some years ago, where Teri and Judy talked about their mutual love of horses. As we parted Judy asked Teri to come and ride with her sometime at their farm in Vermont, and of course that never happened, because Teri and I are the sort of people who are afraid of imposing, and fear that that sort of invitation might be pro forma rather than genuine. Now of course we wish we had put it to the test.

I am so thankful for Fred’s life and work and example, and I will miss him, and the world will miss him. May you rest in peace, good and faithful servant.

One more tiny thing: One autumn day in 1985, Fred came to our shabby apartment because he wanted to see my recent acquisition: an original Macintosh, complete with an ImageWriter printer. (My mom, who worked in a bank, had arranged a loan for me — the two items cost nearly three thousand bucks, as much as a car, and a fifth of my annual salary. But I had a dissertation to write and a determination not to take forever doing it.) Fred was quite taken with these devices, and ordered his own when he got back to Vermont; so I always smiled when I got ImageWriter-printed letters from him, like this one: