from Introduction to IBM Data Processing Systems (1968)

Stagger onward rejoicing

from Introduction to IBM Data Processing Systems (1968)

When the guide of conduct is a moral ideal we are never suffered to escape from perfection. Constantly, indeed on all occasions, the society is called upon to seek virtue as the crow flies. It may even be said that the moral life, in this form, demands a hyperoptic moral vision and encourages intense moral emulation among those who enjoy it…. And the unhappy society, with an ear for every call, certain always about what it ought to think (though it will never for long be the same thing), in action shies and plunges like a distracted animal….

Too often the excessive pursuit of one ideal leads to the exclusion of others, perhaps all others; in our eagerness to realize justice we come to forget charity, and a passion for righteousness has made many a man hard and merciless. There is indeed no ideal the pursuit of which will not lead to disillusion; chagrin waits at the end for all who take this path. Every admirable ideal has its opposite, no less admirable. Liberty or order, justice or charity, spontaneity or deliberateness, principle or circumstance, self or others, these are the kinds of dilemma with which this form of the moral life is always confronting us, making a see double by directing our attention always to abstract extremes, none of which is wholly desirable.

— Michael Oakeshott, “The Tower of Babel”

I’ve always had great admiration for those who, in the chaos that generally characterises the present, sensed from the start the enormous dangers of Nazi-fascism and courageously denounced it. But do we still have the capacity to be as far-seeing? Do the conditions exist today for the long view?

Sometimes I think I understand why we women increasingly read novels. Novels, when they work, use lies to tell the truth. The information marketplace, battling for an audience, tends, more and more, to transform intolerable truths into novelistic, riveting, enjoyable lies.

Another follow-up on my baseball post. I’m getting two kinds of feedback: (a) you’re a moron, sabermetrics is awesome, and (b) you’re absolutely right, sabermetrics is terrible.

Let me emphasize a point that I think is perfectly clear in the piece itself: I love sabermetrics. I started reading Bill James in, I think, 1981; I have written fan letters to him, Rob Neyer, and (later) Voros McCracken (for heaven’s sake); when James came up with the earliest serious attempt to evaluate fielding, Range Factor, I spent countless hours that should have been devoted to my doctoral dissertation trying to improve it — using (by the way) pencil, paper, and a TI SR-50 calculator. I was pontificating about the uselessness of assigning wins and losses to pitchers when Brian Kenny was scarcely a gleam in his father’s eye. If in those days one of those sabermetricians had offered me a job as an assistant, I would’ve dropped out of grad school in an instant.

So in many ways it has been enormously gratifying to me to see the undoubted insights and revelations of serious statistical study make their way into the practices of professional baseball. But such changes have had some unforeseen consequences, and my post was largely about those.

This, by the way, is what those of us with a conservative disposition are supposed to do: When everyone else is running to embrace some new exciting opportunity, we warn that there will be unforeseen consequences; and then, when we have been (as we always are) ignored, we help conduct the postmortem and point out what those consequences actually were. (I was, needless to say, not allowing my conservative side to have a voice when I was so absorbed in sabermetrics — but that was because I never for one second imagined that people running professional baseball organizations would pay attention.)

Now, we might actually like the new opportunity. We might think that on balance it’s worthy to be pursued. So we don’t necessarily stand athwart history shouting Stop. We might instead stand judiciously to the side and quietly ask Do you know what you’re getting into? Because there will be trade-offs. There are always trade-offs.

This is a follow-up to my just-posted essay on my unchosen-but-apparently inexorable declining interest in baseball. My chief point there is that baseball has increasingly converged on a set of Best Practices but that convergence has made baseball less interesting to watch. (And my secondary point is that this is ironic because the practices now being converged upon are the ones I used to cheerlead for when they were far less common.)

That’s the way it has turned out in baseball, but it doesn’t always turn out that way. Take basketball, for instance, and more particularly all the controversy in the last NBA season about Lonzo Ball’s peculiar jump shot: I can remember a time when Lonzo’s technique wouldn’t have been unusual at all. When I first started watching basketball, in the 1970s, there were some weird-looking shots, let me tell you. The most notorious of these was the Jamaal Wilkes slingshot, but Jamaal had a lot of competition. Gradually, though, coaches at all levels came to understood that certain ways of holding and releasing the ball simply made for far greater and more consistent accuracy than others, and players started getting the relevant guidance even in their first organized games. So we have seen a very widespread convergence on the Best Practices of Shooting a Basketball.

And the result has been great for the game. It wasn’t just implementing the three-point line that created the free-flowing, open, spread-the-floor offense that the Golden State Warriors delight us with; it was the rise of a generation of players who have the shooting technique to take advantage of that line. In at least this one situation in this one sport, standardization of technique has led to increased creativity and possibility; in baseball, I fear, just the opposite has happened.

(I am now thinking that I ought to write a short book or long essay called “Rationalism in Sports” to serve as a counterpart to Oakeshott’s “Rationalism in Politics.”)

Are we then to deduce that we should forget God, lay down our tools, and serve men in the Church – as though there were no Gospel? No, the right conclusion is that, remembering God, we should use our tools, proclaim the Gospel, and submit to the Church, because it is conformed to the kingdom of God. We must not, because we are fully aware of the internal opposition between the Gospel and the Church, hold ourselves aloof from the Church or break up its solidarity; but rather, participating in its responsibility, and sharing the guilt of its inevitable failure, we should accept it and cling to it. — I say the truth in Christ, I lie not, my conscience bearing witness with me in the Holy Ghost, that I have great sorrow and unceasing pain in my heart. This is the attitude to the Church engendered by the Gospel. He who hears the gospel and proclaims it does not observe the Church from outside. He neither misunderstands it and rejects it, nor understands it and – sympathizes with it. He belongs personally within the Church. But he knows also that the Church means suffering and not triumph.

— Karl Barth, The Epistle to the Romans

An eye-opening post from Douglas Rushkoff, describing what happened when he was asked to give a talk about “the future of technology” — and ended up instead being peppered with questions by five high-powered hedge-fund managers:

They had come with questions of their own. They started out innocuously enough. Ethereum or bitcoin? Is quantum computing a real thing? Slowly but surely, however, they edged into their real topics of concern.

Which region will be less impacted by the coming climate crisis: New Zealand or Alaska? Is Google really building Ray Kurzweil a home for his brain, and will his consciousness live through the transition, or will it die and be reborn as a whole new one? Finally, the CEO of a brokerage house explained that he had nearly completed building his own underground bunker system and asked, “How do I maintain authority over my security force after the event?”

The Event. That was their euphemism for the environmental collapse, social unrest, nuclear explosion, unstoppable virus, or Mr. Robot hack that takes everything down.

This single question occupied us for the rest of the hour. They knew armed guards would be required to protect their compounds from the angry mobs. But how would they pay the guards once money was worthless? What would stop the guards from choosing their own leader? The billionaires considered using special combination locks on the food supply that only they knew. Or making guards wear disciplinary collars of some kind in return for their survival. Or maybe building robots to serve as guards and workers — if that technology could be developed in time.

What a world we live in.

Trollope’s Phineas Redux, like the other Palliser novels, has a domestic plot and a political plot, and the political plot here spins out from the decision by Mr. Daubeny, the Prime Minister, to come up with a bill for the disestablishment of the Church of England. (Daubeny is a stand-in for Benjamin Disraeli, who never did anything quite like this. But we’ll set aside the real-life correspondences for this post.) This a curious, indeed a shocking, decision because Daubeny is a Conservative, and the Conservative Party in the Victorian era was very much the party of the Church. How could be betray the very heart of his constituency this way?

The answer is that in the recent election his party lost their majority, and in ordinary circumstances it would be incumbent on him to resign. So he creates extraordinary circumstances. His idea, it appears — we are not privileged to know his mind — is that most of his own party will stand with him as a matter of disciplinary obedience, while the many Liberals who have long wanted disestablishment will vote with him across party lines. Thus, on the basis of this single bill-to-come — he hasn’t produced it yet, only announced his plan to — Daubeny can remain in his place as P.M.

Some Liberals are willing to join Daubeny; some, following their leader Mr. Gresham (= Gladstone), are determined to oppose him; some are uncertain. Those uncertain ones want to see the Church disestablished — and, by the way, not necessarily because they dislike the Church: some of the most devoted churchmen in England have long wanted disestablishment in order to free the Church to preach and teach the Gospel without political interference — but they do not believe that Daubeny would do the job properly. They suspect that anyone capable of acting as cynically as Daubeny does cannot possibly carry through the process of disestablishment in a competent and appropriate way.

All of which puts me in mind of Brexit. As a strong proponent of subsidiarity, I am temperamentally disposed to welcome any effort at devolution. I’d love to see Britain freed from accountability to Brussels — and, for that matter, Scotland freed from accountability to England. (I’m even open to the restoration of the Republic of Texas — but that’s a story for another post.) I will always seek to move in the direction of localism and will always be suspicious of institutional cosmopolitanism. I am therefore supportive of Brexit in principle.

But a Brexit designed and managed by these people? I don’t think so. They are more cynical than Mr. Daubeny and less — far less — competent. It’s a feeling I often have with the Trump administration as well: even on those relatively rare occasions when I think they have a good policy in mind, I simply don’t believe that they can carry out that policy honestly, fairly, and successfully. In politics, principle is important; but good principles can produce political disasters when implemented by buffoons.

Peter Tarka, Boxes; via Things Magazine

Peter Tarka, Boxes; via Things Magazine

My friend Dan Cohen recently wrote,

Think about the difference between a blog post and a book: one can be tossed off in an afternoon at a coffee shop, while the other generally requires years of thought and careful writing. Not all books are perfect — far from it — but at least authors have to wrestle with their subject matter more rigorously than in any other context, look at what others have written in their area, and situate their writing within that network of thought and research.

This is absolutely true — as I know from long experience with both genres. But what if there’s a more enlightening comparison? What if, instead of comparing a book to a blog post, you compared it to a blog? If a bog post is too small to compare to a book, a blog might be too big — keep on blogging long enough and you can have enough words to fill several books. If that’s the case, then one might find it interesting to compare a book to, say, a particular tag on a long-standing blog.

An example: For some time now I’ve been thinking of writing a book about John Ruskin. And I still might. But I’ve been led to consider such a book by gradually gathering drawings and quotes by Ruskin on this blog (there are also a few Ruskin entries at Text Patterns). Suppose that, instead of architecturally writing that book, I simply contented cultivating my Ruskin garden? (See this post for the architecture/gardening distinction.) More images and more quotations, more reflection on those images and quotations. What might emerge?

Well, certainly nothing that any scholar would cite. (How would that even be done? All the handbooks to scholarly documentation are still struggling with how to cite websites and individual articles — citing tags is not even on their radar, I suspect.) But I would certainly learn a lot about Ruskin; and perhaps the sympathetic reader would also.

In some ways this would be a return to what I did a few years ago with my Gospel of the Trees site, which arose because what I wanted to say about trees just couldn’t be made to fit into a book, in part because it refused to become a linear narrative or argument and in part because it was so image-dependent and book publishers don’t like the cost of that. But the advantage of a tag over a standalone site is that each post can have other tags as well, which lead down other paths of reflection and information, in a Zettelkasten sort of way.

My friend Robin Sloan tweeted the other day — I’m not linking to it because Robin always deletes his tweets after a few days — that, despite the many calls these days to return to the good old days of Weird Indie Blogging, there are still plenty of charmingly weird things being posted on the Big Media sites, especially YouTube. Point taken: no doubt this is true. But for my purposes the problem with the Big Media sites is the absolute control they have over association: you don’t decide what is related to your post/video/audio, they do. “If you liked this you may also like….” A well-thought-out tagging system on a single blog creates chains of associated ideas, with the logic of association governed by a single mind (or in the case of a group blog, a set of intentionally connected minds). And such chains are powerful generators of intellectual and aesthetic value.

I really do think that the Back to the Blog movement, if we can call it a movement, is so timely and so important not only because we need to, as I have put it, tend the digital commons, but also because we were just beginning to figure out what blogs could do when their development was pre-empted by the rise of the big social media platforms. Given the accelerated pace at which our digital platforms have been moving in recent years, blogs may best be seen as an old, established, and now neglected technology.

I think it was also Robin Sloan who recently directed my attention to this Wikipedia page on the late Nintendo designer Gunpei Yokoi, who promoted what he called “Lateral Thinking with Seasoned Technology”: finding new and unexpected uses for technologies that have been around for a while and therefore (a) have clear patterns of use that you can rely on even when deviating from them, and (b) have decreased in price. Nintendo’s Wii system is the classic example in the gaming world of this way of thinking: some of us will remember that when the Wii was introduced critics were flabbergasted by its reliance on previous-generation processors with their limited graphics capabilities, and were certain that the console would be a total flop. Instead, everyone loved it.

Blogging, I want to argue, is a seasoned technology that is ripe for lateral thinking. The question for me, as I suggested in my previous post, is whether I am willing to set aside the conventional standards and expectations of my profession in order to pursue that lateral thinking — in order, that is, to give up practicing architecture and going in for a good deal of gardening.

More ideas about ideas: Given my current interest in intellectual gardening rather than architecture, in allowing ideas to emerge rather than trying to generate them by a brute-force attack, I am reconsidering the way I have historically used my blogs, and wondering whether there’s not a better path to intellectual substance than the one I’ve been following.

This has been my M.O. going back to the relatively early days of Text Patterns, when I was working on The Pleasure of Reading in an Age of Distraction: Use the blog to generate and try out ideas, get feedback from readers, develop the ideas a little further … and then put on the brakes. But why did I put on the brakes? Because I knew that I was getting close to the point at which there would be so much of the book’s contents online that a publisher wouldn’t want to buy it. And so the idea-generating stage of the project would effectively come to an end.

Not altogether, of course; I could still write in notebooks or sketch ideas or whatever. But two things were missing: the felt need in writing a public post to achieve at least some minimal level of coherence, and the feedback from readers. Moreover, when you’ve been generating ideas using a particular method and then are forced to switch to another one, you tend to lose momentum. So effectively I found myself working with the ideas that I had generated to that point in the project — even when I didn’t feel that I had explored my chosen topics as thoroughly as I would have liked. And this happened more than once, most recently with my idea for a book on what I called Anthropocene theology.

So in these situations the limits and boundaries of my projects are set, not by the inner logic and impetus of those projects, but by the preferences of the publishing industry. But that’s a superficial take. Why, after all, should I allow the publishing industry to set those boundaries? Because in my line of work the highest-denomination currency is the book. I have my current job because of publishing books — Baylor simply would not have sought me out and hired me had I not been able to list several books on my CV.

Put it this way: If I had never blogged a single word I would have precisely the same job I have now; if I had blogged millions of words without publishing books I would not have a job.

But, you may say, at this point in my career why don’t I just do what I want? I have tenure; I have no administrative ambitions (indeed, just the reverse); I am a Distinguished Professor and there’s no such thing as an Extremely Distinguished Professor or Sun-God Professor. If I am feeling the demands of the publishing world as a heavy yoke why not just throw it off?

Well, I might. But I hesitate for two reasons, or maybe it’s one reason with two parts.

So if I were to do the thing I am contemplating — pursue big intellectual projects all the way to their completion here on this blog — my university’s administrators would be unhappy, the publishers who want to publish my stuff would be unhappy, my magnificent literary agent would be unhappy, and some part of me would be unhappy.

But what if, by following SOP for my profession, I limit my ability to think? What if I curtail the development of ideas and end up fitting them into familiar boxes rather than following them to surprising and new and fascinating places? Isn’t that a heavy price to pay for professional adequacy?

More on all this in the next post.

Tom Phillips, Brian Eno

oil on canvas

35.6 x 25.4 cm

1984-85

collection: the artist

I once devised a television project whose abbreviated ghost now forms, not inappropriately, an introduction to the film I worked on with Jake Auerbach (Artist’s Eye: Tom Phillips, BBC2 1989). The title was to be Raphael to Eno: it traced the lineage of pupil and teacher back through Frank Auerbach, Bomberg, Sickert etc. until, after an obscure group of French Peintres du Roy, it emerged via Primaticcio into the light of Raphael. Thus I find that at only twenty removes I am a pupil of Raphael. Brian Eno as a student of mine (initially at Ipswich in the early sixties) therefore continues that strange genealogy of influence as the twenty-first.

I cite that simply because it’s awesome.

The relationship between Phillips — one of whose most famous works is A Humument, an ongoing-for-decades collage/manipulation/adaptation of a Victorian book — and Eno is a fascinating one in the history of aleatory or, as I prefer, emergent art.

I’ve been talking about all this with Austin Kleon — whose newspaper blackout poems are descendants or cousins of A Humument — who not only knows way more about all this than I do but who also has been posting some great stuff lately on the themes of patience, waiting, and what I recently called “re-setting your mental clock.” See for instance this post on Dave Chappelle’s willingness to wait for the ideas to show up at his door.

And of course that post circles back to Eno — so many useful thoughts about being a maker of something circle back to Eno — quoting from this article:

“Control and surrender have to be kept in balance. That’s what surfers do – take control of the situation, then be carried, then take control. In the last few thousand years, we’ve become incredibly adept technically. We’ve treasured the controlling part of ourselves and neglected the surrendering part.” Eno considers all his recent art to be a rebuttal to this attitude. “I want to rethink surrender as an active verb,” he says. “It’s not just you being escapist; it’s an active choice. I’m not saying we’ve got to stop being such controlling beings. I’m not saying we’ve got to be back-to-the-earth hippies. I’m saying something more complex.”

In another talk, one in which he also spoke of control and surrender, he developed another contrast, between creativity-as-architecture and creativity-as-gardening:

And essentially the idea there is that one is making a kind of music in the way that one might make a garden. One is carefully constructing seeds, or finding seeds, carefully planting them and then letting them have their life. And that life isn’t necessarily exactly what you’d envisaged for them. It’s characteristic of the kind of work that I do that I’m really not aware of how the final result is going to look or sound. So in fact, I’m deliberately constructing systems that will put me in the same position as any other member of the audience. I want to be surprised by it as well. And indeed, I often am.

What this means, really, is a rethinking of one’s own position as a creator. You stop thinking of yourself as me, the controller, you the audience, and you start thinking of all of us as the audience, all of us as people enjoying the garden together. Gardener included. So there’s something in the notes to this thing that says something about the difference between order and disorder. It’s in the preface to the little catalog we have. Which I take issue with, actually, because I think it isn’t the difference between order and disorder, it’s the difference between one understanding of order and how it comes into being, and a newer understanding of how order comes into being.

I was texting with Austin about all this earlier today:

This is all good for me to reflect on right now, in this season of heat and uncertainty.

Just one more quick thought about yesterday’s post: I’ve done this kind of thing before, but usually by trying to delete Twitter altogether. This time I’m continuing to use Twitter to share links, but I am making it very difficult to look at Twitter. And that seems to work much better for me.

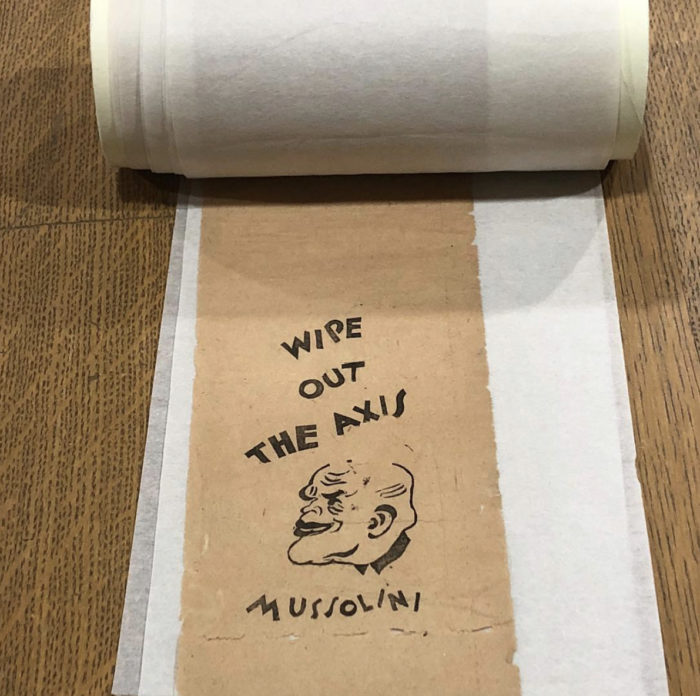

Made by the Randolph Novelty Company in Chicago during World War II; via the Newberry Library’s Instagram

William Moran, from the Newberry Library

I’m already getting some emails in response to my earlier post, and they’re incredibly generous and kind. The message tends to be: Your writings do make a difference, so please write that book! Again, that’s amazingly kind, and God bless y’all for the support. But at the risk of sounding totally ungrateful and churlish, I have to admit that that’s just the response I was afraid I would get. Afraid, because that’s a message that encourages me to consider results and effect — the kinds of considerations that are always subject to counter-evidence, and to unhealthy externalizations of the motives for writing. What I need instead is to think — and to take plenty of time to think — of what I need to do, of what projects I myself most completely believe in. Simply put: I am past the point in my career at which I can write books because other people want them. So if you would like for me to keep writing books, and if you would I bow before you, then maybe instead of exhorting me you might pray for me? If you did I would be even more in your debt.

It is worrisome that despite the soaring temperatures of Austin, the current Prayer Book conversations take place in an ecumenical winter. There are numerous important reasons why things have changed in our dialogues with other groups since the 1960s and ’70s, but a profound question remains largely untouched in this debate: How will our liturgy reveal and help create the unity of the Body of Christ, whose relationship with the Episcopal Church is, well, inexact and incomplete?

This shouldn’t mean we just borrow the insights of other traditions as ritual toys. One of the faintly tragic elements on display in the 1979 Prayer Book are the numerous borrowings from Orthodox liturgy, which reflect not just scholarly knowledge, but prayerful conversations with Russian and Greek scholars of the mid-20th century who were then genuine dialogue partners. It is hard to find such engagement with eastern Christianity in the Episcopal Church now, beyond the somewhat hollow testimony of facsimile icons in Church bookstores.

McGowan here identifies what I think is most worrisome about the current push for revision of the BCP: it is radically exclusionist. The Orthodox don’t matter, Catholics don’t matter, Anglicans outside of the U.S. don’t matter, non-revisionist Episcopalians don’t matter. Literally no one in the world matters except the revisionists themselves.

If a man in the fullness of his days, at the end of his life, can pass on the wisdom of his experience to those who grow up after him; if what he has learned in his youth, added to but not discarded in his maturity, still serves him in his old age and is still worth teaching the then young — then his was not an age of revolution, not counting, of course, abortive revolutions. The world into which his children enter is still his world, not because it is entirely unchanged, but because the changes that did occur were gradual and limited enough for him to absorb them into his initial stock and keep abreast of them. If, however, a man in his advancing years has to turn to his children, or grandchildren, to have them tell him what the present is about; if his own acquired knowledge and understanding no longer avail him; if at the end of his days he finds himself to be obsolete rather than wise — then we may term the rate and scope of change that thus overtook him, “revolutionary.”

— Hans Jonas, from Philosophical Essays (1974), p. 46

Soccer is beautiful because soccer is hard. Most popular sports artificially enhance the human body. Soccer diminishes it. Instead of giving players a bat, a racket, protective armor, or padded gloves — tools that allow players to reach farther, return a ball faster, absorb harder hits, or hit harder themselves — soccer takes away players’ hands. It prohibits the use of the nimblest part of the body, and then it says, “Be nimble.” Moreover, because the action in soccer so seldom stops, because there are so few moments when play resets to a familiar starting point, soccer requires players to work within the limitations it imposes for much longer, and through many more situational complications, than other sports.

Clumsiness and confusion are thus inherent to the game, and this is soccer’s perverse genius, because what happens when you force people to move a ball around in a highly unnatural way is that they find a way to do it. Human ingenuity and talent manage to outwit the restrictions the game places on them. And when this happens at a high enough level — when a goal is scored after a breathtaking run, or when a series of one-touch passes makes it seem as though players are telepathically linked — then what results is beauty, because creativity and grace have momentarily overcome the forces that oppose them.

This is perfect. I might suggest that Brian’s description pairs nicely with the account of the offside rule, and the emergent complexity of on-pitch action, I give here.

The cosmic horizon is changing. Hooper has worked out how this will affect our neighborhood in the universe, which astronomers call the Local Group. This is the set of about 50 nearby galaxies that are gravitationally bound to the Milky Way and on course to collide sometime within the next trillion years to form a single supergalaxy. Consequently, the Local Group will be humanity’s home for the foreseeable future. Over billions of years, we might even colonize it, hopping from one star system to another and exploiting each sun’s energy along the way.

However, the accelerating expansion of the universe is sending galaxies over the horizon at a rate that is increasing. “As a result, over the next approximately 100 billion years, all stars residing beyond the Local Group will fall beyond the cosmic horizon and become not only unobservable, but entirely inaccessible,” says Hooper.

That’s a problem for an advanced civilization because it limits the number of new stars that are available to exploit. So the question that Hooper investigates is whether there is anything an advanced civilization can do to mitigate the effects of this accelerating expansion.

I have to say, this concern is high on my list also: the possibility of running out of stars for human beings to exploit.

More seriously, I am bemused by this line of thinking. Billions of humans live in poverty, are daily endangered by hunger or disease or war; we lack a cure for cancer — we lack a cure for the common cold — we lack a cure for male pattern baldness —; and yet there are people worrying that we will eventually have no more stars to plunder to satisfy our energy demands.

Well, enough of this. Time for me to get back to planning the first year of my reign as God-Emperor of Terra. Because it could happen, you know, and I’d rather not be caught unprepared.

What is God? It is only a subject that has inspired some of the finest writing in the history of Western civilization—and yet the first two pages of Google results for the question are comprised almost entirely of Sweet’N Low evangelical proselytizing to the unconverted. (The first link the Google algorithm served me was from the Texas ministry, Life, Hope & Truth.) The Google search for God gets nowhere near Augustine, Maimonides, Spinoza, Luther, Russell, or Dawkins. Billy Graham is the closest that Google can manage to an important theologian or philosopher. For all its power and influence, it seems that Google can’t really be bothered to care about the quality of knowledge it dispenses. It is our primary portal to the world, but has no opinion about what it offers, even when that knowledge it offers is aggressively, offensively vapid.

If Harold Bloom or Marilynne Robinson had engineered Google, the search engine would have responded to the query with a link to the poet John Milton, who is both challenging on the subject of God and brave on the subject of free speech—and who would have been a polemical critic of our algorithmic overlords, if he had lived another four hundred years.

On Monday Robert Macfarlane will be hosting a Twitter book club on W. G. Sebald’s The Rings of Saturn, which is one of the most compelling and memorable books I have ever encountered. I’ve read it three times now and hope to read it at least twice more.

Years ago, in the first flush of my fascination with it, I bought a copy and sent it to Frederick Buechner, who, if you don’t know, is one the best writers of English now living. He read it, and wrote back to say, “I have no idea what any of that means but it is absolutely mesmerizing.” Which is a pretty good summary.

I’ve just read, with great interest, John Lanchester’s latest essay on the global financial situation, and as always, Lanchester is informative, precise, lucid, and compelling — though maybe not wholly compelling. At one point he writes,

Remember that remark made by Robert Lucas, the macroeconomist, that the central problem of depression prevention had been solved? How’s that been working out? How it’s been working out here in the UK is the longest period of declining real incomes in recorded economic history. ‘Recorded economic history’ means as far back as current techniques can reach, which is back to the end of the Napoleonic Wars. Worse than the decades that followed the Napoleonic Wars, worse than the crises that followed them, worse than the financial crises that inspired Marx, worse than the Depression, worse than both world wars. That is a truly stupendous statistic and if you knew nothing about the economy, sociology or politics of a country, and were told that single fact about it – that real incomes had been falling for the longest period ever – you would expect serious convulsions in its national life.

Right — and yet — there aren’t any “serious convulsions” in the UK, or the USA for that matter, are there? Lanchester also writes, “In the US there is enormous anger at oblivious, entitled, seemingly invulnerable financial and technological elites getting ever richer as ordinary living standards stay flat in absolute terms, and in relative terms, dramatically decline.” But is the anger really so enormous? I’d say there’s not nearly as much as there ought to be, or that one would (as Lanchester suggests) expect there to be.

And many of the people who have been hit hardest by an economic system in which, Lanchester rightly says, the rich in pursuing with laser-focus their own further enrichment “have seceded from the rest of humanity,” say almost nothing about that situation but wax eloquent and wroth about the supposedly imminent danger of their being murdered by vast roaming gangs of illegal immigrants. Brexit and Trump are not about fixing economic inequality — which is why Trump’s version of populism has almost nothing to do with the “Share Our Wealth” vision of Huey Long, back in the day, but rather focuses with a passionate intensity on stoking fear of anyone and everything not-American.

So why is that? Why, though certainly there is some anger at the global-capitalist system, is there, relative to reasonable expectations, so little? Why don’t people care that, since the massively reckless incompetencies of 2008, almost nothing has changed? (Lanchester documents the insignificance of the changes very thoroughly.)

The first answer is that almost nobody — almost nobody — remembers what happened in 2008. And why don’t they remember? Because of social media and smartphones.

I cannot, of course, provide documentary proof for that claim. But as the Marxists used to say I believe it is no accident that the shaking of the foundations of the global economy and “the longest period of declining real incomes in recorded economic history” happened just as the iPhone was taking serious hold on the imagination of the developed world, and Facebook and Twitter were becoming key components of everyday life in that world. On your smartphones you can get (a) a stream of prompts for visceral wrath and fear and then (b) games and distractions that accomplish the suddenly-necessary self-soothing. Between the wrath and fear and the subsequent soothing, who can remember what happened last week, much less ten years ago? Silicon Valley serves the global capitalist order as its Ministry of Amnesia. “What is it I was so concerned about?”

I am re-reading the Palliser novels, for the first time in 20 years, which means I have largely forgotten what happens in them, and I am reminded that Trollope really is the most underrated novelist in the world. The casualness of his manner, and his intermittent insistence is that he is telling simple and insignificant stories, disguise from us just how penetrating his mind was, how clearly he sees the inmost workings of his characters’ lives, and how justly he deals out condemnation and mercy alike. I’m reading Can You Forgive Her? right now, and there is an extraordinary moment when George Vavasor has entered Parliament, having run a successful race thanks to the money he has extracted from his cousin Alice, whom he has manipulated into agreeing to marry him though he knows perfectly well that she does not love him. So when he comes to see her immediately after his election, he begins by thanking her for her financial contribution to his success – thanks which she does not want – but then strives to extract from her some expression of affection which she knows she does not feel. And Trollope pauses in the middle of George’s conversation with Alice and says, with brutal simplicity, “He should have been more of a rascal or less.” It’s one of the most devastating comments that any novelist has made about one of his characters.

George wants to be treated as an honorable man without being one. He wants Alice to give him credit for virtues and intentions which he has in a thousand ways made it clear that he does not possess. He insists upon being given credit for traits which as soon as he walks away from her he repudiates mockingly. He should have been more of a rascal or less. He should have frankly acknowledged the terms on which he and Alice have come to an agreement, or realized that he desperately needed to amend his life. But he does neither, and by doing neither makes himself and Alice equally miserable.

Can You Forgive Her? contains plenty of the broadish comedy that Trollope did so well – the protracted attempts of the farmer Mr Cheeseacre to woo the widow Greenow really are funny, even if there is more of it than one might think ideal – but the effect of these scenes is primarily to relieve the tension of what in other respects is a rather agonizing novel to read. Some may think “Ah, well, we know that everything will turn out all right in the end” – but we do not know that, not in a Trollope novel. Some of his most appealing and memorable characters (Lady Laura Kennedy, Lily Dale) do not receive the eucatastrophic resolution we would rightly expect from a lesser writer. If you know that, you know that you cannot simply expect a happy ending for his protagonists.

Which makes it all the more delightful when they get one.

For the most part, BLM activists – like the post-1965 SNCC activists, the Black Panther Party, and assorted other radical black groups before them – exhibit little interest in, or comprehension of, the larger lessons of history. This is because they lack the deep spiritual and moral insight that must be the grounding for any sustainable movement. Having rejected the God of their fathers, they have also rejected the fatherhood of God.

This philosophical rejection is an act of spiritual and cultural suicide. Failure to discern the demonic character of white supremacy limits these activists’ ability to understand the fight they are engaged in, and hinders their efforts to develop long-term strategies. They can only describe the sadistic violence they witness and never fully understand or conquer it, so long as they ignore its spiritual source.

More importantly, they fail to use the only means of combatting the demonic: intercessory prayer. Instead, they are easily sucked into the spirit of the demonic themselves as they resort to violence, anger, and hate – a failing less common in the BLM movement than in Antifa, though the danger applies to both.

African-American Christianity has continuously confronted the nation with troubling questions about American exceptionalism. Perhaps the most troubling was this: If Christ came as the Suffering Servant, who resembled Him more, the master or the slave? Suffering-slave Christianity stood as a prophetic condemnation of Americas obsession with power, status, and possessions. African-American Christians perceived in American exceptionalism a dangerous tendency to turn the nation into an idol and Christianity into a clan religion. Divine election brings not preeminence, elevation, and glory, but — as black Christians know all too well — humiliation, suffering, and rejection. Chosenness, as reflected in the life of Jesus, led to a cross. The lives of his disciples have been signed with that cross. To be chosen, in this perspective, means joining company not with the powerful and the rich but with those who suffer: the outcast, the poor, and the despised.

The real problem is that [the scooters] just appeared out of nowhere one day, suddenly seizing the sidewalks, and many citizens felt they had no real agency in the decision. They were here to stay, whatever nonusers felt about them.

Which was all by design. The scooter companies were just following Travis’s Law. In Santa Monica, Bird’s scooters appeared on city streets in September. Lawmakers balked; in December, the city filed a nine-count criminal complaint against Bird.

Bird responded with a button in its app to flood local lawmakers with emails of support. The city yielded: Bird signed a $300,000 settlement with Santa Monica, a pittance of its funding haul, and lawmakers authorized its operations.

If you love the scooters, you see nothing wrong with this. But there was a time, in America, when the government paid for infrastructure and the public had a say in important local services. With Ubers ruling the roads, Birds ruling the sidewalks, Elon Musk running our subways and Domino’s paving our roads, that age is gone.

To me, the most interesting and significant element of the opposition to Amy Coney Barrett is the inability of some of her critics to achieve even the most basic comprehension of the character of an organization like People of Praise. Many Americans are so thoroughly catechized into the Atomic Theory of Human Life — the belief that all significant life-decisions are properly made by autonomous monads, with only the State to set boundaries and provide a safety net — that a genuinely functional community, in which some of the burdens of decision-making are distributed throughout a network of people bound to one another by mutual affection, can only be seen as a “cult.”

Alan Jacobs is a writer who has a degree of talent in this app that I would love for you haven’t heard anything from the app that I would love for you haven’t seen you haven’t been able for you a couple weeks was a couple weeks is a couple weeks I would like a couple more opportunities for y’all and I will make you happy again if I can get it done

It happens that I have practically some connexion with schools for different classes of youth; and I receive many letters from parents respecting the education of their children. In the mass of these letters I am always struck by the precedence which the idea of a “position in life” takes above all other thoughts in the parents’—more especially in the mothers’—minds. “The education befitting such and such a STATION IN LIFE”—this is the phrase, this the object, always. They never seek, as far as I can make out, an education good in itself; even the conception of abstract rightness in training rarely seems reached by the writers. But, an education “which shall keep a good coat on my son’s back;—which shall enable him to ring with confidence the visitors’ bell at double-belled doors; which shall result ultimately in establishment of a double-belled door to his own house;—in a word, which shall lead to advancement in life;—THIS we pray for on bent knees—and this is ALL we pray for.” It never seems to occur to the parents that there may be an education which, in itself, IS advancement in Life;—that any other than that may perhaps be advancement in Death; and that this essential education might be more easily got, or given, than they fancy, if they set about it in the right way; while it is for no price, and by no favour, to be got, if they set about it in the wrong.

— John Ruskin, Sesame and Lilies. I know a number of people who work to recruit students to Baylor (where I now teach) and to other universities, and they have commented that it is virtually impossible to get parents interested in what kind of education, what kind of experience, their children will have in their undergraduate years. Parents only want to know whether their children will get into medical school or dental school or law school — the four years of undergraduate education are simply a very large hurdle to be leaped over to get to that STATION IN LIFE that they want for their children. Many, many parents do not care one iota about what their offspring will actually do and read and think between the ages of 18 and 22, as long as whatever it is helps (or at least does not impede) their admission to professional training.

Update: I should add that I don’t blame the parents for this — they’re being asked to pay a shocking amount of money for their children’s education, and they are desperately hoping for a return on investment. I get that. But when your job is to teach those young people, the situation is regrettable — especially since so many of the students have adopted the attitudes of their parents.

Reading this post by Rod Dreher, which considers (among other things) the extent to which overt hostility towards tradition-minded Christians is a product of the Trump years or, by contrast, predates the current shitstorm — spoiler alert: it’s the latter — I was reminded of a conversation I had on Twitter some years ago with a friendly, easygoing academic acquaintance. I had posted something in relation to religious freedom, and he replied along these lines: I just want you to know that religious freedom is not something I see any value in.

I said, You know religious freedom is deeply embedded in the Constitution, right? And of course he did. And that it’s a key part of the United Nations Universal Declaration of Human Rights? Yeah, he knew that too. I don’t expect legal commitments to religious freedom to go away any time soon, he said, but I wish I could get rid of them. They have negative social utility.

The conversation has stuck with me primarily because, as I noted above, this is a perfectly friendly and easygoing guy, and someone that I am confident strives to treat all his students fairly, even when they’re Christian fundamentalists. But if he could wave a magic wand and eliminate all legal protections of religious freedom, he would, simply because he thinks religion in general does more harm than good. It occurred to me that there are probably millions of people like him in America, which I find a sobering thought, to say the least.

TEC and ACNA are still suing one another. The day, now foreseeable, when the suits are over, one way or another, is the day when a serious conversation between them could occur. As an Episcopalian, I would challenge my own church with this question: If we can consider full communion with Methodists, why could we not, on that post-litigious day, open ecumenical talks with our own fellow Anglicans? Perhaps the offer would be refused. But then again, a day finally came, for example, when combatants in Northern Ireland were willing to talk with one another. Could such a day come for us? Would the Archbishop of Canterbury not be an appropriate convener of such a meeting, someday, given his own evangelical commitments and his interest in reconciliation?

Let us hope.

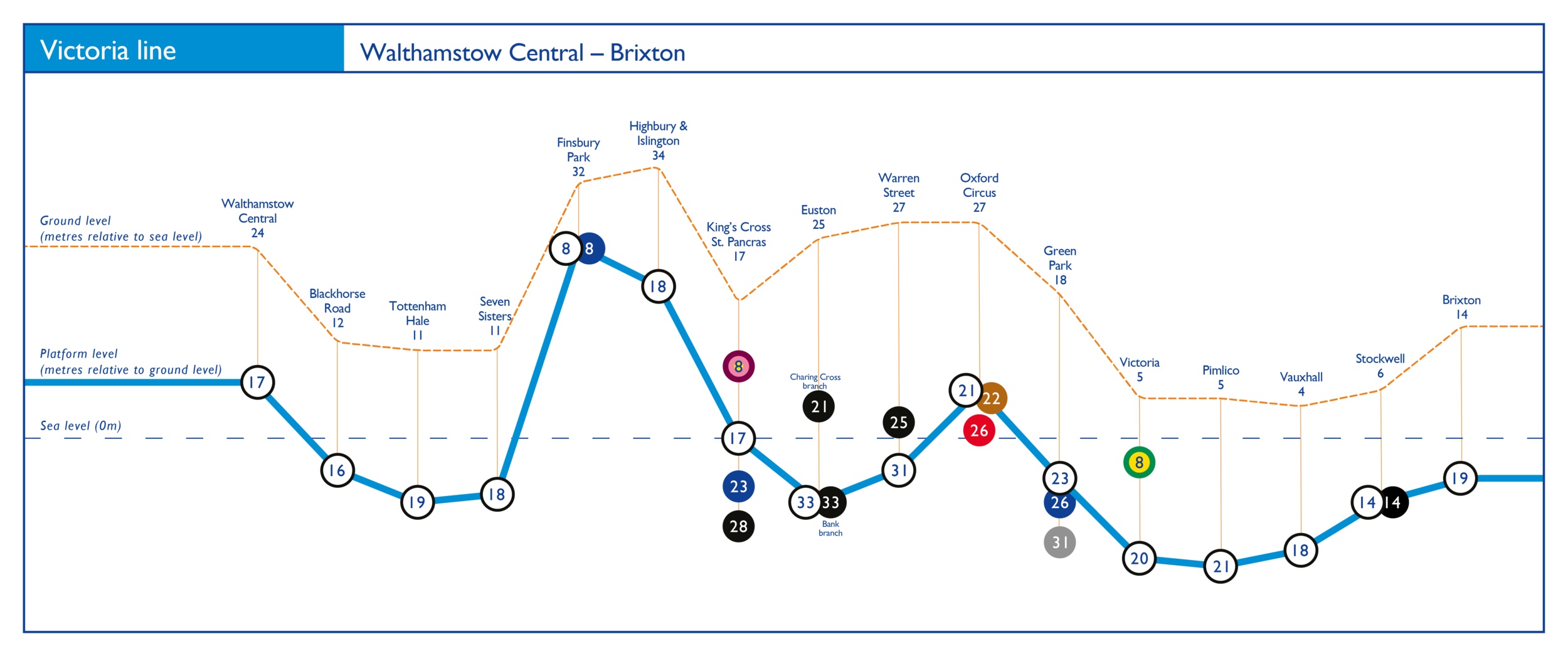

This is amazing. Daniel Silva has created a series of maps showing just how far underground any given station of the London Underground is. Note that the brown dotted line traces the changes in ground elevation, while the blue line below shows the depth of the railway. Some of the lines (like the Victoria, above) maintain a general consistency of depth in relation to the ground, but others don’t. Silva has created a simple representation of what had to have been some very complicated engineering decisions.

This is amazing. Daniel Silva has created a series of maps showing just how far underground any given station of the London Underground is. Note that the brown dotted line traces the changes in ground elevation, while the blue line below shows the depth of the railway. Some of the lines (like the Victoria, above) maintain a general consistency of depth in relation to the ground, but others don’t. Silva has created a simple representation of what had to have been some very complicated engineering decisions.

I have long loved the Atlantic and am proud of my association with it, but every time the Aspen Ideas Festival rolls around my inner Unabomber emerges and wants to burn the entire endeavor to the ground. It’s the only time of year when reading posts in the Atlantic makes me so angry I want to go kick something.

I think I would be okay with it if the shindig had a more accurate name, like the Ideas from Our Technocratic Overlords Festival. Often it seems that there are no ideas at the Aspen Ideas Festival that don’t serve to consolidate transnational technocracy, even the ones that seem to be offering critiques.

Maybe Code for America is reconsidering some of its priorities but it’s still Code for America and its “solutions” inevitably involve deepening people’s dependence on Big Tech. (“We can give you a texting tool that allows you to text with people and it’s been shown to decrease the rates of failure to appear.”)

Is there a crisis of affordable housing in Silicon Valley? Indeed there is. So let’s see what Google can do about it!

This is how it goes, session after session, year after year.

My recommendation: stop calling it an Ideas festival until at least two or three ideas featured there don’t defer to, appeal to, or consolidate the authority of, the world’s biggest technology corporations.

I’m exaggerating, of course. There are always a few sessions about “sustainable development” and “rethinking nutrition” and “civic engagement.” But nine times out of ten there’s an app for that — and, probably, an accelerated Master’s degree at a mid-tier university for only $80,000, please click through to apply for a loan.

For those of us who think there are interesting non-smartphone-connected ideas to be had about family, or faith, or poetry, Aspen is the one place you don’t want to be this summer, or any other.

In her book The Craft of Thought, Mary Carruthers identifies the purpose of memorization in medieval intellectual culture:

The orator’s “art of memory” was not an art of recitation and reiteration but an art of invention, an art that made it possible for a person to act competently within the “arena” of debate (a favorite commonplace), to respond to interruptions and questions, or to dilate upon the ideas that momentarily occurred to him, without becoming hopelessly distracted, or losing his place in the scheme of his basic speech. That was the elementary good of having an “artificial memory.” …

I repeat: the goal of rhetorical mnemotechnical craft was not to give students a prodigious memory for all the information they might be asked to repeat in an examination, but to give an orator the means and wherewithal to invent his material, both beforehand and — crucially — on the spot. Memoria is most usefully thought of as a compositional art. The arts of memory are among the arts of thinking, especially involved with fostering the qualities we now revere as “imagination” and “creativity.”

Today people will tell you that memorization is the enemy of creativity; these medieval thinkers understood that precisely the opposite is true: the more you have memorized the greater will be your powers of invention.

WI’m reading Emily Wilson’s marvelous translation of The Odyssey this summer, and its emphasis on giving freely to “foreigners and beggars” keeps grabbing me by the throat. When in doubt, listen to the poets! (This passage is from 6.204-219.) pic.twitter.com/WFTDLDqUnf — Dr Catherine Clifford (@CRCliff) June 24, 2018

I’m looking forward to reading Wilson’s translation of the Odyssey, though I will admit to being put off a bit by the intensity of some of the praise, which tends to give Wilson credit for something that Homer does and that is fairly represented in pretty much every other translation. (Thus Alexander Pope and/or William Brooke in 1726: “By Jove the stranger and the poor are sent; / And what to those we give to Jove is lent. / Then food supply, and bathe his fainting limbs / Where waving shades obscure the mazy streams.” Etc. etc.) That emphasis is in the poem, not the translation.

It is a key theme in the Odyssey, though, and one that I often call particular attention to when teaching. This is the second major point at which the importance of hospitality to the stranger appears. Earlier, when Athena (disguised as Mentor) is escorting Telemachus around to see a bit of the world, they arrive at Nestor’s home at Pylos and are welcomed warmly and offered roasted meat and red wine and “deep-piled rugs” to sleep on — but when they come to the much grander home of Menelaus at Sparta they are greeted with considerable suspicion by one of Menelaus’s companions. Now, to be sure, Menelaus chastises the man for not being more generous, but Homer is showing us something here about the difference between a household that’s instinctively and naturally welcoming and, on the other hand, one where the welcome is grudging at best. Mentor wants Telemachus to learn the right way to live, and the right way to live requires hospitality to strangers.

When correcting his companion, Menelaus explains why: Could we have made it home from Troy, he asks, if people had not been hospitable to us? This was not a world, as I remind my students, in which you could drive up to a Holiday Inn and pull our your credit card. We do best when we extend a helping hand to those in need, not least because one day soon we could be among the endangered and dependent.

But the lessons of hospitality don’t come easily to those — like the suitors of Penelope, hanging out in Odysseus’s house and eating his food without earning a damned thing for themselves — who think that what they need will always be within reach. They are spoiled, arrogant, grasping; and in all these respects just the opposite of Nestor and his family, of the princess Nausicaa, and even of Odysseus’s poor old goatherd Eumaeus, who even in his poverty takes care of a man he thinks to be a ragged beggar, because “strangers and beggars come from Zeus.”

So be generous to the homeless because it’s the right thing to do; but if you’re not going to do it because it’s right, do it because someday you may need some generosity yourself. And if you don’t, you could end up like those suitors, whose end is — spoiler alert — not pretty.

When does a life worth living cease to become so? When one can no longer eat and must use a feeding tube? A ventilator? When one loses mobility, or memory? What about pain—can one live with a little, but not a lot? How much is a lot, exactly? And then there is the monster in its own category that is depression. I know many people living with each of these conditions, and the thing I know is this: the view from outside is invariably impoverished. The human brain just lacks the imagination to fathom a life lived well that is so physically or neurologically different from one’s own. Living without capacities one has come to take for granted is only seen as loss of capacity, and therefore loss in total. A life no longer a life. But ask disabled people, and they will tell you: their lives are worth having.

Religion: A Viewpoint Diversity Blind Spot?:

How could Heterodox Academy address this lacuna? It could, for example, promote the use of surveys or studies to better understand the religious makeup of faculty, administrators, and students — and how they are affected by the lack of viewpoint diversity, the narrowing space for legitimate debate, unfair recruitment and promotion practices, and intolerance of religion on campus. It could highlight the issues affecting religious groups and individuals working or studying in universities and colleges more in its blog posts, weekly updates, and podcasts. It could make a greater effort to involve academics from theology or religious studies fields. It could publish articles parsing the differences between political conservatives and religious academics—not all of the latter are members of the former (and vice versa) —and explore how these differences affect research methods, interests and findings.

Despite the myriad challenges to protecting political viewpoint diversity and freedom of speech in academia today, HxA has boldly undertaken the challenge. Yet, it must now go one step further and also explore the limits and potential of religious belief on campus as well.

That’s Seth Kaplan of Johns Hopkins. Kaplan is right that the viewpoint-diversity movement, especially as represented by Heterodox Academy, has been focused on bringing conservative or even centrist ideas into the academic conversation rather than on finding a place for religious views. I think there are two reasons for that.

If indeed members of HxA have these reservations, they are reasonable ones. All meaningful conversations happen within certain structures of constraint, and methodological naturalism has done a pretty good job of providing those structures, and has done so for so long that most academics are not even aware that they are methodological naturalists. Richard Rorty’s famous claim that religion is a conversation-stopper need not be true, but one can see why he thought it was.

So can anything be done? If there were two good reasons for the discomfort, maybe there are two possible solutions:

Whether or not I’m right about any of this, it seems to me that these are issues that viewpoint-diversity advocates need to debate.

From Ross Douthat’s column today:

But perhaps the simplest way to describe what happened with the surrogacy debate is that American feminists gradually went along with the logic of capitalism rather than resisting it. This is a particularly useful description because it’s happened so consistently across the last few decades: Whenever there’s a dispute within feminism about a particular social change or technological possibility, you should bet on the side that takes a more consumerist view of human flourishing, a more market-oriented view of what it means to defend the rights and happiness of women.

This reminds me very much of an argument Paul Kingsnorth makes in his provocative Confessions of a Recovering Environmentalist:

We are environmentalists now in order to promote something called ‘sustainability’. What does this curious, plastic word mean? It does not mean defending the non-human world from the ever-expanding empire of Homo sapiens sapiens, though some of its adherents like to pretend it does, even to themselves. It means sustaining human civilisation at the comfort level that the world’s rich people – us – feel is their right, without destroying the ‘natural capital’ or the ‘resource base’ that is needed to do so.

It is, in other words, an entirely human-centred piece of politicking, disguised as concern for ‘the planet’. In a very short time – just over a decade – this worldview has become all-pervasive. It is voiced by the president of the USA and the president of Anglo-Dutch Shell and many people in between. The success of environmentalism has been total – at the price of its soul.

“Sustainability,” then, is the magic word that allows the worldwide corporate-scaled environmental movement to become utterly comfortable with transnational capitalism. As Kingsnorth points out, the movement’s single-minded focus on reducing carbon emissions allows the energy companies to offer lucrative-for-them “solutions” to carbon-based “problems,” which may well lead to the utter despoiling of places that environmentalists used to care about preserving, even when that meant not sustaining our current levels of consumption. “Motorway through downland: bad. Wind power station on downland: good. Container port wiping out estuary mudflats: bad. Renewable hydro-power barrage wiping out estuary mudflats: good. Destruction minus carbon equals sustainability.”

Environmentalism has made the same deal that (per Douthat’s argument) today’s American feminism has made. Both movements were scrupulously attentive to the depredations of transnational capitalism up to the moment when transnational capitalism said “We can give you stuff you want at no additional cost — to you, anyway.” Then the critiques dissolved.

In Trump’s world, you fit into one of three categories. You may be a mark, you may be leverage, you may be a loser.

Trump wants to make deals, which means he wants to win deals. His understanding of deal-making is that someone fleeces and someone gets fleeced. It is his ambition to be the fleecer.

So you could be his mark, the one he wants to fleece. That’s what the American electorate was in the 2016 election. That’s what Kim Jong Un was recently, which is why Trump didn’t mind flattering him. (As a general rule, if Trump praises you that means he hopes to fleece you.)

Or you could be leverage, which is what the children in the Trump/Sessions detention centers are. They are not human beings, they are tokens or counters to be used to try to get a deal with the current mark, which is Congress.

But if you attempt in any way to impede the deal, or if you refuse to participate in it, or protest it, or even just call it what it is, you are a loser.

In Trump’s world there can be no compassion, no fairness, no justice, no truthtelling, no principles, no standards, no ethics, no convictions, no respect for others, no self-respect, no friends, no allies, no prudence, no thought for the future, no discernment, no wisdom, no religion, no humanity. Only deals. Only marks, leverage, and losers.

The distinction between Hitchens or Dawkins and those like myself comes down in the end to one between liberal humanism and tragic humanism. There are those who hold that if we can only shake off a poisonous legacy of myth and superstition, we can be free. Such a hope in my own view is itself a myth, though a generous-spirited one. Tragic humanism shares liberal humanism’s vision of the free flourishing of humanity, but holds that attaining it is possible only by confronting the very worst. The only affirmation of humanity ultimately worth having is one that, like the disillusioned post-Restoration Milton, seriously wonders whether humanity is worth saving in the first place, and understands Swift’s king of Brobdingnag with his vision of the human species as an odious race of vermin. Tragic humanism, whether in its socialist, Christian, or psychoanalytic varieties, holds that only by a process of self-dispossession and radical remaking can humanity come into its own. There are no guarantees that such a transfigured future will ever be born. But it might arrive a little earlier if liberal dogmatists, doctrinaire flag-wavers for Progress, and Islamophobic intellectuals got out of its way.

An interview with Richard Powers::

The modern human assumption that trees, plants and all other wildlife are “just property” is, to Powers, the root of our much greater species problem. “Every form of mental despair and terror and incapacity in modern life seems to be related in some way to this complete alienation from everything else alive. We’re deeply, existentially lonely.

“Until it’s exciting and fun and ecstatic to think that everything else has agency and is reciprocally connected we’re going to be terrified and afraid of death, and it’s mastery or nothing.” To that end, Powers hopes his book will be part of the restoration of a tradition that has all but ceased to exist in modern literature. “We are incredibly good at psychological and political dramas, but there’s another kind of drama – between the humans and the non-humans – that disappeared in the late 19th century, once we thought we had dominion over the Earth. Because we won that battle.

“But now we know we didn’t, actually. And until you resolve that question, how do we live coherently at home on this planet, the other two kinds of stories are luxuries.”

The Overstory is next on my reading list.

Two comments about my essay in the Guardian today, both of them regarding points that had to be cut in editing:

1) There’s no sense in which a Hillary Clinton administration could have mean “death” to Christians and conservatives, but, as I’ve argued often, the next time Democrats control the federal government they’ll make life much harder for all Christian institutions. In relation to all this, the question that has arisen in my mind in the past year or is this: If a Trump administration makes life easier for me and my fellow Christians but harder for many of the most vulnerable people in American society, do I not have an obligation to support my neighbor in preference to myself? (I still don’t expect to vote for either of our two major parties, though.)

2) I have of course known for many years about the great “temporal bandwidth” passage in Gravity’s Rainbow, a book I have taught several times, but the relevance of that passage to our present moment was brought to my attention by my friend Edward Mendelson in this essay. That debt was registered in my own essay but didn’t make it through the editing process. (My excellent editor, Amana Fontanella-Khan, had to curb some of my loquaciousness.)

Also, I have to admit to taking some pleasure in the fact that in the past 24 hours my writing has been published in the Guardian and the Weekly Standard.

Earlier this week I drove from my home in Waco to West Texas: first to the little town of Goldthwaite, then South through San Saba, Llano, Fredericksburg, Kerrville; then a long westward haul on I-10. On such a drive you start in mostly flat farm country — corn, soybeans — and move gradually into the Hill Country, with its limestone escarpments and ridges mostly covered in junipers. (People in Texas call those trees cedars but they aren’t.) Gradually the trees become smaller and sparser until, eventually, you find yourself in the Chihuahuan desert.

There’s a nice new rest area on I-10 between Fort Stockton and Balmorhea that looks like this:

The temperature when I took the photo was 106°. I got back in the car and resumed my journey. I took the Balmorhea exit and started headed up into the Davis Mountains. About half an hour later, here’s what I saw:

That’s the McDonald Observatory, on Mount Locke. But just look at that grass! — a veritable greensward. And all those trees! (Also, the temperature was 87°.) All this just half an hour from sheer desert. What’s the deal?

The deal is that the Davis Mountains constitute a sky island. Far above the desert that surrounds them, the mountains, the tallest of which is Mount Livermore at 8200 feet, have their own distinct climate. They get far more rain than the desert does, and as a result support quite different species of flora and fauna. Sometimes those species can evolve in distinctive ways, just as they do on actual islands, because of their isolation from other communities of their kind.

It’s a fascinating phenomenon — and the transition is really something to experience.

Sanders comments on family separations at the border: “It is very biblical to enforce the law” https://t.co/5DiL1C4FHt — CNN Politics (@CNNPolitics)

Attorney General Jeff Sessions makes a similar argument: “Persons who violate the law of our nation are subject to prosecution. I would cite you to the Apostle Paul and his clear and wise command in Romans 13, to obey the laws of the government because God has ordained them for the purpose of order.”

But when Obama was president the relevant biblical passage wasn’t Romans 13:1, it was Acts 5:29. The goalposts have moved — and when there’s a another Democratic president and/or Congress, they’ll move again. Conservative Christians would never have countenanced electing a president who has been divorced — until Reagan came along. When Bill Clinton was president, character in the occupant of the Oval Office was everything; now it’s nothing, or, really, less than nothing.

The lesson to be drawn here is this: the great majority of Christians in America who call themselves evangelical are simply not formed by Christian teaching or the Christian scriptures. They are, rather, formed by the media they consume — or, more precisely, by the media that consume them. The Bible is just too difficult, and when it’s not difficult it is terrifying. So many Christians simply act tribally, and when challenged to offer a Christian justification for their positions typically grope for a Bible verse or two, with no regard for its context or even its explicit meaning. Or summarize a Sunday-school story that they clearly don’t understand, as when they compare Trump to King David because both sinned without even noticing that David’s penitence was even more extravagant than his sins while Trump doesn’t think he needs to repent of anything. But hey, as a Trump supporter once wrote to me: “Now we are fused with him.”

And that’s it, that’s the law, that’s the whole of the law.

But I think Jeff Sessions actually knows that the position he and Sanders articulate is inadequate. In his statement he lets slip one dangerous word: “I do not believe scripture or church history or reason condemns a secular nation state for having reasonable immigration laws. If we have them, then they should be enforced.”

Ah, you shouldn’t have let that word sneak in there, Mr. Jefferson Beauregard Sessions III. It might lead people to ask questions, to wit:

Start going down this road and you could end up sitting at your kitchen table trying to parse the way Martin Luther King Jr. distinguishes just and unjust laws in his “Letter from the Birmingham Jail.” And we wouldn’t want that, would we? Better simply to say “Romans 13:1 says it, I believe it, and that settles it” — at least until the Democrats get back in power.

Why Lorrie Moore Writes | The New Republic:

“How to Become a Writer” begins with the urge to write and ends in the desert to which such a desire may deliver the writer — not once, as ending or punishment, but daily, as a kind of side trip, between sentences. (Among the reader’s final instructions: “Quit classes. Quit jobs. Cash in old savings bonds. Now you have time like warts on your hands.”)

Every time I see this well-known line by Lorrie Moore I wonder what it must be like to live in a world where people who want to be writers have savings bonds to cash in.

This sounds really useful! Unless, well, you happen to read Bill Bryson:

Now imagine reading a nonfiction book packed with stories such as this—true tales soberly related—just before setting off alone on a camping trip of your own into the North American wilderness. The book to which I refer is Bear Attacks: Their Cause and Avoidance, by a Canadian academic named Stephen Herrero. If it is not the last word on the subject, then I really, really, really do not wish to hear the last word. Through long winter nights in New Hampshire, while snow piled up outdoors and my wife slumbered peacefully beside me, I lay saucer-eyed in bed reading clinically precise accounts of people gnawed pulpy in their sleeping bags, plucked whimpering from trees, even noiselessly stalked (I didn’t know this happened!) as they sauntered unawares down leafy paths or cooled their feet in mountain streams….

Black bears rarely attack. But here’s the thing. Sometimes they do. All bears are agile, cunning, and immensely strong, and they are always hungry. If they want to kill you and eat you, they can, and pretty much whenever they want. That doesn’t happen often, but — and here is the absolutely salient point — once would be enough.

No worries, though! VR to the rescue!

The Law not only prohibited interest on loans, but mandated that every seventh year should be a Sabbatical, a shmita, a fallow year, during which debts between Israelites were to be remitted; and then went even further in imposing the Sabbath of Sabbath-Years, the Year of Jubilee, in which all debts were excused and all slaves granted their liberty, so that everyone might begin again, as it were, with a clear ledger. In this way, the difference between creditors and debtors could be (at least, for a time) erased, and a kind of equitable balance restored. At the same time, needless to say, the unremitting denunciation of those who exploit the poor or ignore their plight is a radiant leitmotif running through the proclamations of the prophets of Israel (Isa 3:13-15; 5:8; 10:1-2; Jer 5:27-28: Amos 4:1; etc.).

So it should be unsurprising to learn that a very great many of Christ’s teachings concerned debtors and creditors, and the legal coercion of the former by the latter, and the need for debt relief; but somehow we do find it surprising—when, of course, we notice. As a rule, however, it is rare that we do notice, in part because we often fail to recognize the social and legal practices to which his parables and moral exhortations so often referred, and in part because our traditions have so successfully “spiritualized” the texts—both through translation and through habits of interpretation—that the economic and political provocations they contain are scarcely imaginable to us at all.